By Inderjit Badhwar

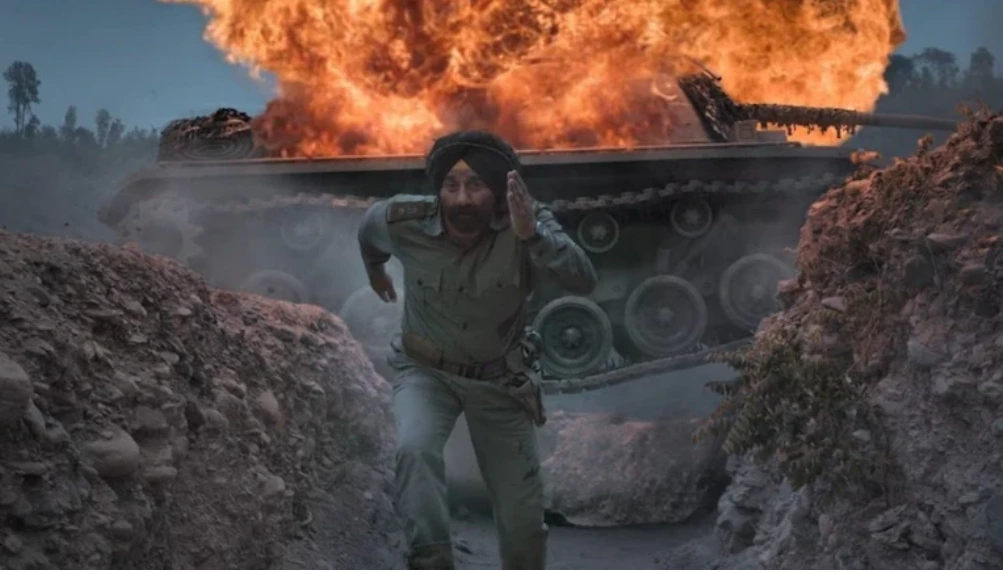

For those seeking the heart-pounding chaos of Gotham—the car chases, explosions, and violent mayhem that punctuated Joker: Folie à Deux’s 2019 predecessor—you’re bound to feel cheated. This film shuns the devilish spectacle, the apocalyptic laughter, and numbing bloodletting that made audiences reel last time. Instead, Joker takes a different path—one that draws you into a theatrical allegory, where sorrow lurks behind every scene like the unspoken melancholy of Busby Berkeley’s gals, whose smiles mask tears behind the brass and drums. It’s a film that will break your heart if you’re willing to look beneath the surface.

Most critics who have panned this work have utterly missed its genius. They’ve approached it as another instalment of the Batman universe or a Marvel spin-off, never realising they should have been viewing it through a Bergmanesque or Kafkaesque lens.

This is not a superhero movie; it is a meditation on despair. In fact, even with its colour palette, the film strikes the mind in grainy black and white, resonating with the heavy weight of reality and the tragedy that lies at its core.

Tragedy reigns in every frame. From the grimy, passionless prison where Joker awaits trial for his previous murders, to his imploding visage as he engages in cramped and joyless lovemaking with Harley Quinn in a dingy cell, the mood is one of relentless gloom. As the film unfolds, we understand one central truth: Joker is already dead. Joaquin Phoenix’s face in the opening shots tells us this immediately—the rest of the movie exists to prove why this is so. It’s not a question of fate; it’s an exploration of inevitability.

This film becomes a tug-of-war—not just between Joker and the world around him—but between director Todd Phillips, Joaquin Phoenix, and the audience. Phillips and Phoenix push a painful reality down the throats of viewers and characters alike, while the world around them begs for fantasy. It’s as though the cast itself, along with the audience, yearns for the Joker of old—the virile, immanent figure who once offered Gotham’s downtrodden an escape, a chance at vengeance, a wild ride through the storm. But that Joker is gone.

Fantasy, it turns out, is what many wanted—and critics, too, missed the film’s central theme of “fantasy as entertainment.” The repeated number, “That’s Entertainment,” becomes the leitmotif, a sardonic nod to an audience desperate to maintain illusion. The powerful Joker of the previous film offered this fantasy. He was an avenging angel, the ultimate escape hatch for Gotham’s wretched—their abused and neglected, whose collective pain he embodied. He thrilled the wealthy, the beautiful people, the theatre-going elite, who saw in him a Marvel comic made flesh.

Even Harley was captivated by this illusion, but unwittingly, she played the role of femme fatale. In love, Joker became Fleck once again, irreversibly human. And this was his fatal flaw. Joker could never survive as a human. His love for Harley shattered the very fantasy he had created, and in doing so, he signed his own death warrant. The human Fleck had to die, tried and convicted not only for his crimes but for betraying those who longed for him to remain the Joker—the untouchable, the fantastical. Even Harley, in the end, turns her back, revealing that she, too, was just another devotee of the illusion.

This film is an extraordinary piece of art, driven by Joaquin Phoenix’s near-flawless artistry and supported by brilliant character performances from an impassioned cast. It masterfully turns fantasy into reality, refusing to indulge the audience’s desire for escape.

Go see it. Joker is not entertainment for entertainment’s sake—it is art, designed to rip away our comforting illusions and force us into deeper reflection. This is not a film that indulges the tooth fairy; it crushes her underfoot, daring us to see the world as it truly is.

LATEST SPORTS NEWS16 hours ago

LATEST SPORTS NEWS16 hours ago

Latest world news16 hours ago

Latest world news16 hours ago

India News15 hours ago

India News15 hours ago

India News15 hours ago

India News15 hours ago

India News5 hours ago

India News5 hours ago

Latest world news5 hours ago

Latest world news5 hours ago