By Sanjiv Bhatia

The recent success of Indian athletes at the Asian games must be applauded. Five Hundred and seventy athletes competed in thirty-nine sports to win a total of 69 medals. It is time now to think ahead on how to build on this success and take Indian sports forward.

The NitiAyog has come up with a plan called First Play which lays down a strategy for getting India 50 medals in the 2024 Olympics. For a country that won two medals in 2016, and has a total of 23 medals over the last 70 years, this goal seems to be a real stretch. What makes this goal sheer delusion, however, is NitiAyog’s plan to get there.

Bureaucrats run the NitiAyog. They are bright people and surely mean well for the country. But they are programmed to find solutions that run through the government machinery. More government involvement, more policies, more regulations, and more committees are their solution to all problems. It is baffling that an institute tasked with transforming India would ignore the inexorable truth that market-based solutions that allow individuals to pursue goals based on their own set of skills and incentives are the best way to achieve optimum performance.

Niti’sFirst Play plan includes, among other things, ‘targeting’ ten priority sports based on past success and something they call ‘high winning potential’. It sounds like the License Raj policy that destroyed India’s economic growth for five decades. Allowing bureaucrats and politicians to pick priority sectors did not work for our economy and will certainly not help Indian sports. If anything, it assures political meddling since prioritised sports will get higher public funds. For example, Haryana, which produces a high number of wrestlers, will unquestionably want wrestling to be a priority sport.

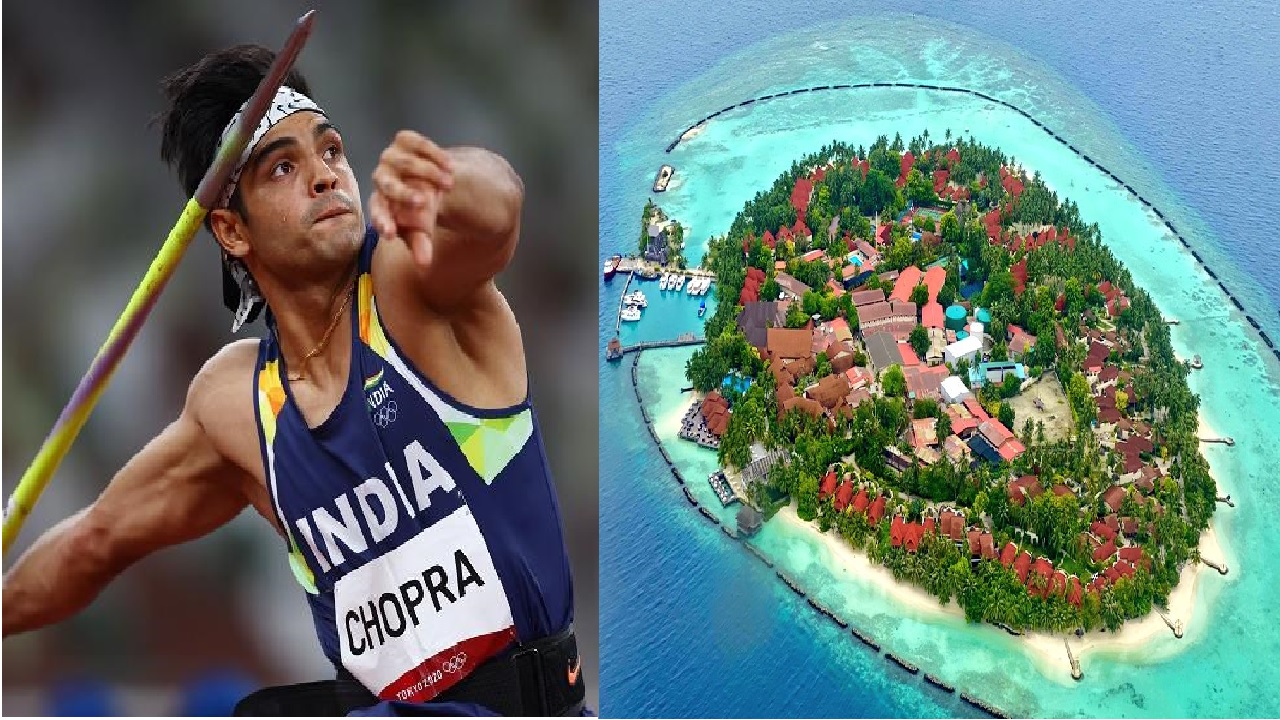

Neeraj Chopra, India’s Javelin throw Gold medallist, would never succeed under Niti’s plan because Javelin would have never been a priority sport. It has no track record of success. Neither would Swapna Barman who won the Gold in Heptathlon nor would we have seen the likes of Milkha Singh and PT Usha winning in a sport like 400 meters which in their days would not have been a priority sport. And DipaKarmakar, the Indian gymnast would not have medalled at the 2016 Olympics, because gymnastics has little history in India and would not be prioritized.

It has always been the success of an elite athlete that increases participation in a sport. It was the success of Mark Spitz that provided an impetus for the next generation of U.S. swimmers like Michael Phelps and not some wacky government prioritisation scheme. Likewise, Usain Bolt’s success has ignited more athletic interest in Jamaica than any government scheme. Let natural talent decide which sports India medals in, not some bureaucrat or politician.

A good model for India to follow is the USA, a country which has dominated world athletics with over 2500 Olympic medals over the last hundred years, and where the government has absolutely no involvement in sports. The United States Olympic Committee is a non-profit organisation funded entirely through private sources, but more importantly, also privately managed. Unlike India, the USA does not have a Ministry of Sports. So, one has to ask the question that with no government funding of its Olympic efforts, and no Ministry for sports how has the U.S. performed better than other countries over the last ten decades?

The answer is straightforward. Government bureaucracies and Ministries are not a help but a hindrance for optimum athletic performance. It is the freedom to pursue one’s dreams and the monetary rewards that follow from winning that has led to an explosion of talent in U.S. sports. Let’s mimic this successful model in India. The country unshackled its economy from government controls in the 1990’s and per capita income grew ten-fold over the next two decades. If India does the same for sports, its medal tally could also increase ten-fold. Let private sports companies develop business models to find, train and support the best athletic talent. A market-based process which creates the right incentives for private companies to unearth the best talent, to provide them with the best in facilities and coaching, and to produce world-class athletes, should be the bedrock of India’s sports policy.

To win 50 Olympic medals the country needs to make sports a business. Athletes, from beginners through to high-performance amateurs or professionals, represent the basis of the sports industry. They are the engine of the sports economy. They create demand for coaches and trainers, they are consumers of manufactured sporting goods, and they use the sporting facilities. High-performance athletes attract people to the stadium for amateur or professional sports events, and their performances are broadcast on TV. The economic activity related to the sport and recreational service industries also has a broad impact on the economy. Thousands of jobs tied directly to sporting activity are created by new companies engaged in the discovery, management, training of athletes, and manufacturing of sporting, athletic and recreation equipment.

The world of professional sports operates entirely in the private domain. Whether it is professional basketball in the form of the NBA, or global soccer clubs like Manchester United, Real Madrid, Chelsea–every one of them is privately owned or has shares traded on a stock exchange. That is the direction for sports in India. Some of it is already happening and private clubs in Cricket, Soccer, Tennis, Badminton, and even Kabaddi have found a way to monetise themselves using the power of private enterprise and the free market.

Private sports clubs and schools, similar to the ones in Norway and Finland, must be encouraged. Private sports management companies armed with the best functional movement and muscle testing equipment could identify potential athletes from a very early age. One of the world’s largest sports management company, IMG, has designed a systematic approach that tests athletes to assess their performance levels using sport-specific standardised tests. There are even some new, but unproven, genetic tests which can show the disposition of a person towards a particular sport. All of this science is now coming into the sports business, and private capital would jump at the opportunity to deploy it in a massive market like India.

Eventually what will make India a successful sporting country is not more government involvement but creating the right incentives for the athletes. And these incentives are best created by a free market which is unencumbered by government control. Corporate sponsorship is a form of survival for most athletes. It covers the cost of living and training for athletes. Private sports management companies could be invited to invest in the development of Indian athletes. These companies are in the business of finding talent, paying for their training, finding the best trainers, coaches and performance psychologists, and eventually benefiting themselves and the athletes they represent by maximising their sponsorship value. Michael Phelps alone has won more medals in the last four Olympics than India has in over seventy years, yet he has never received a penny from the US government; sponsorship pays for his living and training.

In the 2018 budget, the government of India allocated almost Rs 2196 crores for sports. Bureaucrats and politicians still control and run the country’s sports. The NitiAyog’sFirst Play plan is just more of the same thing: more government involvement, more rules, more government agencies, more bureaucracy, and more corruption. India needs to transform the way it thinks about sports. Sports should become an industry with its sports schools, sports clubs, private coaching academies, sports management companies, equipment manufacturers, professional leagues, TV rights, sponsorships etc. The Sports Ministry should be abolished, and all regulatory barriers to entry should be removed to allow private sports management companies to find, adopt, train, support, and convert Indian athletes into world-class medal winners.

The only way to get to 50 medals by 2024 is to get the government out of the business of managing sports. Otherwise, like the bureaucrats at the NitiAyog, we can all keep dreaming.

The author is a financial economist and founder of contractwithindia.com

India News23 hours ago

India News23 hours ago

India News23 hours ago

India News23 hours ago

India News22 hours ago

India News22 hours ago

India News22 hours ago

India News22 hours ago

Cricket news22 hours ago

Cricket news22 hours ago

India News13 hours ago

India News13 hours ago

India News12 hours ago

India News12 hours ago