India News

CBI vs CBI: Both sides argue over Centre’s powers over Director, SC adjourns case till Dec 5

Published

7 years agoon

By

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The hearing on CBI Director Alok Verma’s plea challenging Centre’s order divesting him of his powers and sending him on compulsory leave was adjourned till Wednesday, December 5, after both sides argued over the government’s powers to do so.

The CBI chief was sent on leave following a tussle with his deputy, special CBI director Rakesh Asthana. He has been accused by Asthana of accepting a bribe in a case related to meat exporter Moin Qureshi. Asthana, too, was accused of indulging in corrupt practices by Verma and the CBI had registered a case against him.

When the Supreme Court bench of Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justices SK Kaul and KM Joseph resumed hearing the case today (Thursday, Nov 29), Verma told the Supreme Court that he has been appointed for a fixed period of two years and cannot be transferred.

Verma’s counsel, senior advocate Fali S Nariman told the SC bench that Verma was appointed on February 1, 2017 and “the position of law is that there will be a fixed tenure of two years and this gentleman cannot be even transferred”.

The government had acted in violation of the DSPE Act, the Vineet Narain judgment and various Supreme Court directives that gave the investigating agency’s boss a “secure tenure of two years irrespective of his superannuation,” Nariman argued.

Nariman added there was no basis for the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) to pass an order recommending to send him on leave. He also submitted that transfer or removal of the CBI director cannot be done unilaterally by the government – a charge Verma, many in the legal fraternity and also Opposition leaders have been making against Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Nariman pointed out that the CBI director is chosen, as per law, by a selection committee comprising the Prime Minister, Chief Justice of India and the Leader of Opposition and that the officer can only be transferred or removed after this panel meets and carries out an inquiry on the reasons cited for such action. He pointed out that the government sent Verma on leave on the midnight of October 24 without carrying out this due process.

“There has to be a strict interpretation of the Vineet Narain judgment. This is not the transfer and Verma has been denuded of his power and duties, otherwise, there was no use of the Narain judgment and the law,” Verma’s counsel said.

Delivered by the top court in 1997, the Vineet Narain decision relates to the investigation of allegations of corruption against high-ranking public officials in India. Prior to 1997, the tenure of the CBI director was not fixed and they could be removed by the government in any manner. However, the apex court in the Vineet Narain judgment later fixed a tenure of a minimum of two years for the CBI director to allow the officer to work with independence.

Nariman also referred to the terms and conditions of appointment and removal of the CBI director and concerned provisions of the Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act, 1946.

While the government has claimed that it has not violated any law because Verma has only been sent on leave and not removed him from the post of CBI director, Nariman claimed that stripping the CBI director of his responsibilities was equivalent to his transfer or removal – an action that should not have been carried out with the requisite inquiry by and recommendation of the selection panel. Asserting that dilution of the powers of the CBI chief had “not even been contemplated in the (DSPE) Act”, Nariman said that the government and the Central Vigilance Commission had erred by approving the action taken against Verma.

“When you can’t even transfer the CBI chief under the law, how can you clip his wings without putting this proposal (of divesting him of his charge) before the high-powered panel? I say clip his wings because that seems to be the idea,” Nariman said, adding that divesting the CBI director of his responsibilities is “impermissible” in law.

As Nariman insisted that any action against the CBI director must be taken only after the collegium responsible for his appointment conducts an inquiry, Justice Joseph wondered: “if the CBI chief is caught red-handed taking a bribe, what should be the course of action? You submit that the Committee has to be approached but should the person continue even for a minute?”

As Nariman concluded his submissions stating that he was not referring purely to the facts of the case but also the requirements under the law with regard to the removal or transfer of the CBI director, the bench clarified that it will presently stick to the argument on whether an approval from the high-powered committee was a must before acting against Verma. The bench also said that it would wish to hear the arguments of the Centre and the CVC’s law officers on this specific aspect.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1543495405071{border-top-width: 10px !important;border-right-width: 10px !important;border-bottom-width: 10px !important;border-left-width: 10px !important;padding-top: 10px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #efefef !important;border-radius: 10px !important;}”]On the previous date of hearing on Nov 20, the top court bench of Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justices SK Kaul and KM Joseph had abruptly adjourned the matter after expressing displeasure over alleged “leak” of confidential details related to the case.

As the proceedings began today, Verma’s counsel, senior advocate Fali nariman referred to earlier proceedings in the top court during the Sahara India Real Estate Corpn. Ltd. v. SEBI case, referring to 10 SCC 603, to highlight issues regarding postponement of publication of news reports through a judicial order related to a case. The reference by Nariman was in response to the Chief Justice’s reprimand to Verma and his legal team during the last hearing in the case when the bench was irked over publication of articles that carried the purported response of the CBI chief to a confidential inquiry report against him by the Central Vigilance Commission. Nariman had, during that hearing, pointed out that the article in question had not amounted to any violation of the top court’s order as it was about Verma’s response to the CVC during the probe and not his reply to the inquiry report as was being claimed.

Perhaps satisfied by Nariman’s arguments with regard to the purported “leak”, the bench did not press the matter further.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Following Nariman’s arguments, senior advocate Dushyant Dave began his submissions on behalf of NGO Common Cause which has also impleaded itself in the case with a petition that seeks the top court’s indulgence in the larger matter of the CBI’s autonomy and also on the manner in which M Nageswara Rao was appointed as the agency’s interim chief after Verma was sent on leave.

Chief Justice Gogoi told Dave that he should make submissions only if he has something to supplement the arguments made by Nariman as the court was inclined to discuss only the issue of whether a meeting of the CBI chief’s selection panel should have been convened before the government decided to send Verma on leave.

Dave said that he wishes to highlight aspects of the Vineet Narain judgment which dealt with the appointment and transfer of the CBI director and the role of the CVC in the matter. However, Dave proceeded to make arguments that sounded more as submissions against CBI special director Rakesh Asthana than on aspects that the court wanted him to touch upon.

Chief Justice Gogoi stopped the advocate from diverting the issue and urged him to stick to the aspects the bench had pointed out.

Dave argued that the CBI as an organisation cannot function under the dictation of the central government or the Central Vigilance Commission. Dave’s client has sought the court’s indulgence on the larger question of the CBI’s autonomy.

Dave reiterated earlier arguments made by senior advocate Fali Nariman, appearing for Alok Verma, stating that the Centre had violated the directions laid out under the DSPE Act while sending the CBI director on leave. Asserting that the government’s decision was “against the rule of law” and so, the subsequent order of appointing M Nageswara Rao as the interim chief of the agency was also void, Dave concluded his submissions.

Senior advocate Kapil Sibal then sought the bench’s permission to make submissions on behalf of Congress leader in the Lok Sabha, Mallikarjun Kharge. Though Kharge has not filed a separate petition in the case, Sibal noted that the Congress leader had moved an application to be heard in the case as he, in his capacity of the largest Opposition party in Lok Sabha, is a member of the selection panel that chooses the CBI director.

Kapil Sibal said the power to remove the CBI chief was with the selection committee. The selection committee comprises of the Prime Minister as the chairperson, the Chief Justice of India and the Leader of Opposition.

Sibal argued that the order of chief vigilance commissioner KV Chowdary, like that of the Centre, to divest Verma of his responsibilities and appoint Nageswara Rao as the interim CBI director, was “outside the ambit of power of superintendence of the CVC”.

He added that the CVC’s directive to seal Verma’s office, soon after he was divested of his charge, was passed in violation of the CVC Act. He stated further that while the Act allows the CVC superintendence over the CBI in cases of corruption, it has no provision under which the vigilance commission can seal the office of the CBI director or send the agency’s top officer on forced leave.

“If the power to appoint is with the committee, the power to remove is also with the committee. If this has happened to the CBI director, this may happen to CVC or the Election Commission also,” Sibal said. The senior lawyer said the power of the CVC under Section 8(1)(a)(b) of the CVC Act cannot be used to strip CBI director of his charges.

Sibal was interrupted by Chief Justice Gogoi who asked him to “stick to the points” and not drag in the issue of charges and counter charges between Alok Verma and CBI special director Rakesh Asthana or matters directly linked to CVC KV Chowdary or other institutions. The Chief Justice had, during the pre-lunch proceedings in the case, made it clear to all parties in the case that the bench was inclined to hear only arguments with regard to whether the Centre and CVC had erred in sending the CBI director on leave without convening a meeting of the selection panel.

The Chief Justice then asked Sibal if, as per provisions of the law, the CBI director cannot be transferred or sent on leave or suspended without prior consultation on the issue within the selection committee and its approval. The question had Nariman, Dave and Sibal all reply in unison: “Yes”. The Chief Justice then asked again if any exception could be made to this, and Sibal replied in the negative.

As Sibal concluded his arguments, senior advocate Indira Jaising made a brief intervention saying that her client, CBI officer MK Sinha, does not wish to press for arguments on the petition moved by him. It may be recalled that Sinha’s petition, filed after the CVC completed its inquiry against Verma, had made explosive allegations against senior officials in the government, including national security advisor Ajit Doval, and alleged that the CBI under the new dispensation headed by Rao wanted to derail the probe against Asthana. Sinha was among the CBI officers investing Asthana who were all transferred out of Delhi soon after Rao took interim charge as CBI chief.

Jaising, however, told the court that Sinha wanted to wait for the court to give its final order on Verma’s petition before it could take up his plea.

Senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan then began making his submissions on behalf of AK Bassi, the CBI officer who was heading the probe against Asthana and, like Sinha, was transferred out of Delhi – to Port Blair – after the government decided to send Verma on leave.

Dhavan, too, started with the submission that Section 4B of the DSPE Act grants the CBI director a protected, two year tenure and that it overrides all other rules that may be invoked by the government or any other organization to cut the CBI chief’s tenure short.

Dhavan added that if the law had a lacuna (a possible reference to the bench’s earlier query on whether reference for action against the CBI director must be made to the selection panel if he is caught red handed taking a bribe), it is the Supreme Court that should address it and not the government without any consultative process.

Chief Justice Gogoi questioned Dhavan about the locus standi of his client in the case. The senior advocate replied that Bassi’s transfer was a corollary to the government’s decision to send Verma on leave which in turn was taken after the CBI (under Verma’s stewardship) filed an FIR against Rakesh Asthana. Dhavan argued that if Verma was not removed, Bassi would have continued with his charge of heading the SIT probing Asthana and so, because these sequences are related, he has an obvious locus standi in the case.

The Chief Justice again pressed the same question, asking Dhavan: “You are saying you would not have been transferred if Alok Verma was not sent on leave?” Jaising, still present in the courtroom, said she wanted to respond to this question and proceeded to say that “there was a genuine apprehension that persons investigating (cases against Asthana) will be victimized.

Nariman also intervened to state that he wants the court’s indulgence on the prayer that for the purpose of this case, “divesting of authority” should be treated as the same as “transfer” under the DSPE Act.

Attorney General KK Venugopal, appearing for the Centre, then began with his submissions before the bench. He sought to counter the arguments that only the selection panel has the right to appoint, transfer, suspend or send on leave the CBI director.

He argued that the “appointing authority (for the CBI director) is the central government,” Venugopal claimed that the “power of selection and the final choice for appointment of Director lies with the union government.”

“The appointing authority is the Central government. Selection Committee and appointing authority are different. Centre appoints from the names recommended by the Selection Committee,” Venugopal said.

He then claimed that the question of consulting with the selection committee on the decision to send Verma on leave or to appoint Rao as the interim chief does not arise in light of his submissions.

Venugopal says that the selection committee, in fact, becomes functus officio (a body whose mandate has expired) once the CBI chief is appointed and so there was no requirement for the Centre to seek its approval for sending Verma on leave. He also asserted that Verma continues to be the CBI director despite the government’s order and that he has not been transferred or stripped of the perks of office – only his responsibilities.

The Chief Justice then posed specific questions to Venugopal with regard to relevant sections of the DSPE Act that lay out the process of appointment of the CBI director. Chief Justice Gogoi wondered whether the power of the order to divest Verma of his charge and appoint Rao as the interim chief flows from these provisions of the DSPE Act to which Venugopal replied in the affirmative and added that the superintendence of the CVC on the CBI too was not limited to matters of corruption probes but all aspects of the agency.

The Chief Justice then told the Attorney General that if the court was to proceed on the argument presented by him then while the centre, as appointing authority could have passed the order against Verma, the consequential order following divesting the CBI director of his charge – one that appointed Rao as the interim chief – should have come from the central government too and not the CVC.

Venugopal then responded saying: “the primary concern (while divesting Verma and Asthana of their charge) was to protect people’s faith in the CBI. Its top two officers were at loggerheads and public opinion was turning negative. The government decided to intervene in public interest so that CBI doesn’t lose confidence.”

When Justice Joseph asked Venugopal if the Centre had applied its mind to the complaint filed by Asthana against Verma before divesting the CBI director of his charge, the Attorney General replied saying the government “was not concerned about A or B”.

The bench then adjourned the proceedings for the day and posted resumption of arguments for December 5 while stating: “Should it become necessary to go into the CVC report (of inquiry against Alok Verma), then we might have to defer the hearing to allow all parties to respond on the report.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

You may like

-

No option left: Supreme Court issues extraordinary order in Bengal SIR case

-

Supreme Court declines to hear Kuldeep Sengar’s bail plea in custodial death case

-

Supreme Court raps Meta over WhatsApp privacy policy

-

Gaurav Gogoi accuses Himanta Sarma of misleading court over Miya voter claims

-

Supreme Court flags risk of lawlessness, pauses FIRs against ED officers in Bengal case

-

TVK chief Vijay to appear before CBI in Karur stampede probe

India News

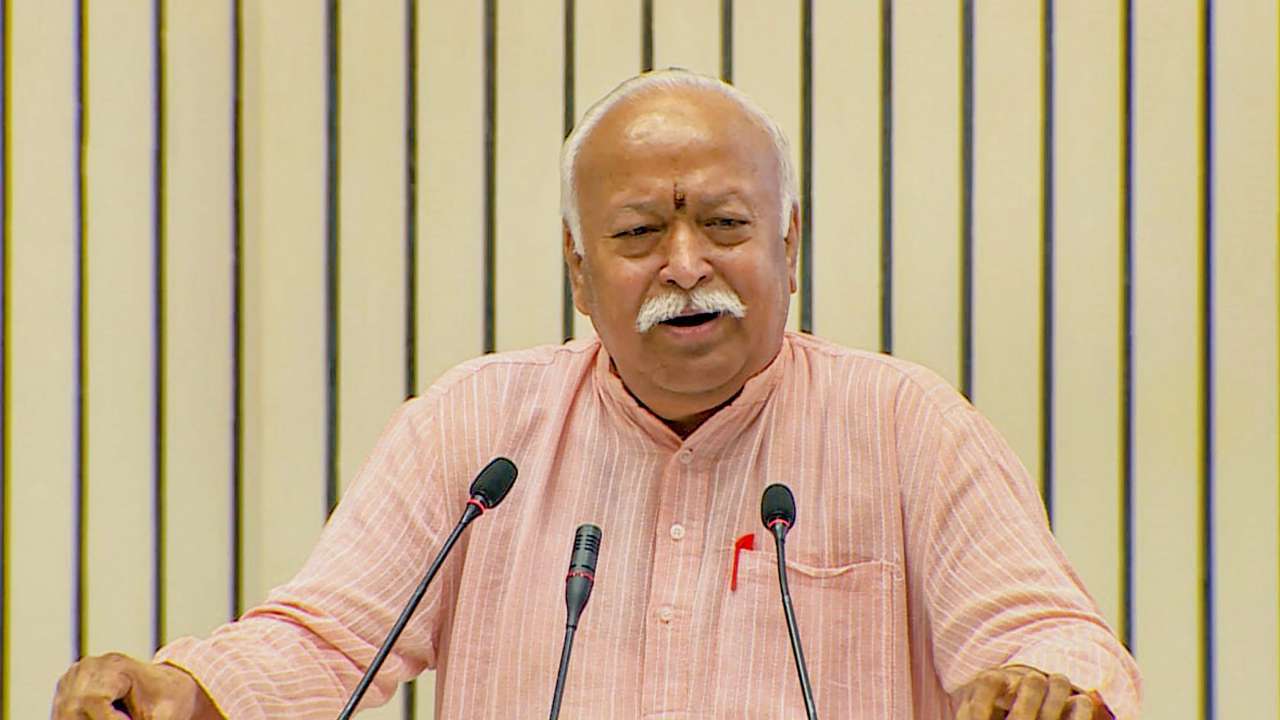

RSS not seeking political power, focused on uniting Hindu society, says Mohan Bhagwat

RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat said the organisation is not seeking political power but is focused on uniting Hindu society and promoting character-building during an interaction with athletes in Meerut.

Published

2 days agoon

February 21, 2026

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) chief Mohan Bhagwat on Friday said the organisation is not driven by any ambition for political power and is instead dedicated to uniting Hindu society and building individual character.

He made the remarks while interacting with nearly 950 national and international sportspersons at Madhav Kunj in Shatabdi Nagar, Meerut, as part of the RSS centenary outreach initiatives. According to participants present at the event, Bhagwat spoke for about 50 minutes and stressed the importance of social harmony and collective responsibility in nation-building.

Quoting Bhagwat, a participant said the RSS’ “sole objective is the organisation of the entire Hindu society and character-building of individuals,” adding that the organisation does not function in opposition to or competition with any specific group.

Emphasis on unity and cultural roots

Explaining his idea of India, Bhagwat said the nation goes beyond geographical boundaries and draws inspiration from figures such as Lord Ram, Lord Krishna, Lord Buddha, Lord Mahavira, Swami Vivekananda, Swami Dayanand and Mahatma Gandhi, participants said.

He reportedly stated that the term “Hindu” reflects unity in diversity rather than caste identity. Differences in modes of worship and deities, he said, do not weaken society as long as cultural harmony is preserved. He added that whenever social unity declined, the country faced crises.

The RSS chief outlined four foundational pillars of society — value inculcation, Sanatan culture, the spirit of dharma and adherence to truth — reiterating that the Sangh’s mission centres on strengthening society through individual development. Volunteers, he said, are active across various spheres of social life and prioritise national interest.

Sports as a tool for nation-building

Addressing the athletes, Bhagwat described sports as a powerful medium for bringing people together. He said nation-building is not the responsibility of any single organisation but of society as a whole.

Referring to Meerut’s historic role in the First War of Independence in 1857, he said the legacy later inspired Keshav Baliram Hedgewar to establish the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in 1925.

Bhagwat also shared five guiding principles for those interested in associating with the RSS — understanding the organisation from within, engaging with its affiliated bodies, supporting its programmes, maintaining dialogue and working selflessly for the nation. He also answered questions from athletes during the session.

Outreach events in Uttar Pradesh

Bhagwat is currently on a tour of Uttar Pradesh. Earlier, he attended a two-day outreach event in Lucknow on February 17 and 18 and had also visited Gorakhpur. During his stay in Lucknow, he briefly met Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, while both deputy chief ministers called on him before he left for Meerut.

Arjuna Award-winning wrestler Alka Tomar described the programme as grand and praised the organisational efforts of RSS volunteers. She said sportspersons must contribute to nation-building and appreciated Bhagwat’s emphasis on working in the national interest.

Para Cricket Club of India player Surya Pratap Mishra of Bareilly, selected for a Sri Lanka tour, said Bhagwat assured support for para athletes to help them enhance the country’s pride. Kabaddi coach Pintu Malik from Shukratal in Muzaffarnagar termed the interaction inspiring, especially the message that players should support one another.

Bhagwat reached Meerut on Thursday night and held breakfast discussions on Friday with representatives from the sports and industry sectors. On Saturday, he is scheduled to interact with members of the intelligentsia, including representatives from education, industry, medicine, literature, art and trade. Entry to the event is restricted to invitees with passes issued by the RSS headquarters.

India News

BJP MLA Vungzagin Valte dies after prolonged battle with injuries from Manipur violence

Manipur BJP MLA Vungzagin Valte has died in Gurugram nearly two years after suffering severe injuries in the 2023 ethnic violence in Imphal.

Published

2 days agoon

February 20, 2026

Manipur BJP MLA Vungzagin Valte, who had been battling severe injuries sustained during the outbreak of ethnic violence in May 2023, died at a hospital in Haryana’s Gurugram on Thursday.

Valte, a representative from the Thanlon assembly constituency in Churachandpur district, was attacked in Imphal when tensions between Meitei and Kuki-Zomi communities escalated into widespread clashes. The assault left him with critical head injuries that significantly affected his mobility and speech.

Long medical struggle after 2023 attack

Following the attack on May 4, 2023, Valte was admitted to a hospital in Delhi, where he spent several months in intensive care. According to his family, he suffered debilitating head trauma that left him wheelchair-bound and dependent on assistance for routine physical movements.

Despite prolonged treatment in the national capital for nearly two years, his health remained fragile. He later returned to Manipur, but complications linked to the injuries persisted.

Earlier this month, Valte complained of breathlessness and chest pain, prompting doctors to stabilise him in intensive care before he was flown to Delhi in an air ambulance on February 8. His condition had reportedly shown slight improvement before the transfer.

Family alleges role of Arambai Tenggol

Valte’s family had alleged that members of the Meitei group Arambai Tenggol were responsible for the attack in 2023. His son, David Mang Valte, had earlier stated that the MLA was assaulted while returning after meeting the then Chief Minister amid the communal crisis involving Kuki, Meitei and Zomi communities.

Valte belonged to the Zomi tribe and was serving as a BJP legislator from Thanlon at the time of his death.

Condolences pour in

Several political leaders expressed grief over his passing. Two-time MLA T Robindro Singh said his last meeting with Valte at Imphal Airport before he was airlifted for advanced treatment remains “deeply emotional and unforgettable.” He described Valte as a kind-hearted and humble leader who was always concerned about the welfare of the people.

Valte’s death marks the end of a prolonged and painful chapter that began with the outbreak of ethnic unrest in Manipur in 2023.

India News

Amit Shah launches Rs 6,900 crore Vibrant Village Programme-II in Assam

Amit Shah has launched the Rs 6,900 crore Vibrant Village Programme-II in Assam to develop 140 villages along the Bangladesh border with improved infrastructure and employment opportunities.

Published

2 days agoon

February 20, 2026

Union Home Minister Amit Shah on Thursday launched the second phase of the Vibrant Village Programme in Assam, announcing a Rs 6,900-crore investment aimed at strengthening development in border areas.

The initiative seeks to transform 140 villages along the Bangladesh border in Assam into centres of modern education, employment and infrastructure. Shah formally inaugurated the programme at Natanpur village in the Barak Valley region of the state.

Focus on education, jobs and infrastructure

Addressing the gathering, Shah said the programme would ensure that border villages receive facilities on par with other parts of the country. He credited Prime Minister Narendra Modi for prioritising development in these regions.

“Today, we are officially beginning the Vibrant Village Programme-II, and through this, we will bring development to bordering villages and facilities like any other place across the country. This has been possible because of Prime Minister Narendra Modi,” Shah said.

He added that Natanpur would not be known merely for its proximity to the border but for excelling in education, employment generation, road connectivity, telecommunications and electricity.

Coverage across 17 states

According to Shah, the Centre has earmarked Rs 6,900 crore under Vibrant Village Programme-II to develop 334 blocks and 1,954 villages across 17 states.

In Assam alone, nine districts, 26 blocks and 140 villages have been identified under the scheme. Shah said all amenities in these villages would match those available in other villages across India.

“There was a time when border villages were called the last villages and lacked many amenities, but Prime Minister Narendra Modi decided that all border villages will be the first villages. Now these villages will be first in road, sanitation, drinking water, communications, employment and education,” he said.

The programme aims to strengthen infrastructure and socio-economic conditions in border areas, particularly those along the Bangladesh frontier in Assam.

India studying implications after US Supreme Court strikes down Trump’s global tariffs

RSS not seeking political power, focused on uniting Hindu society, says Mohan Bhagwat

PM Modi meets Sri Lankan President Dissanayake at AI summit, reviews connectivity agenda

Trump signs 10% global tariffs after US Supreme Court setback