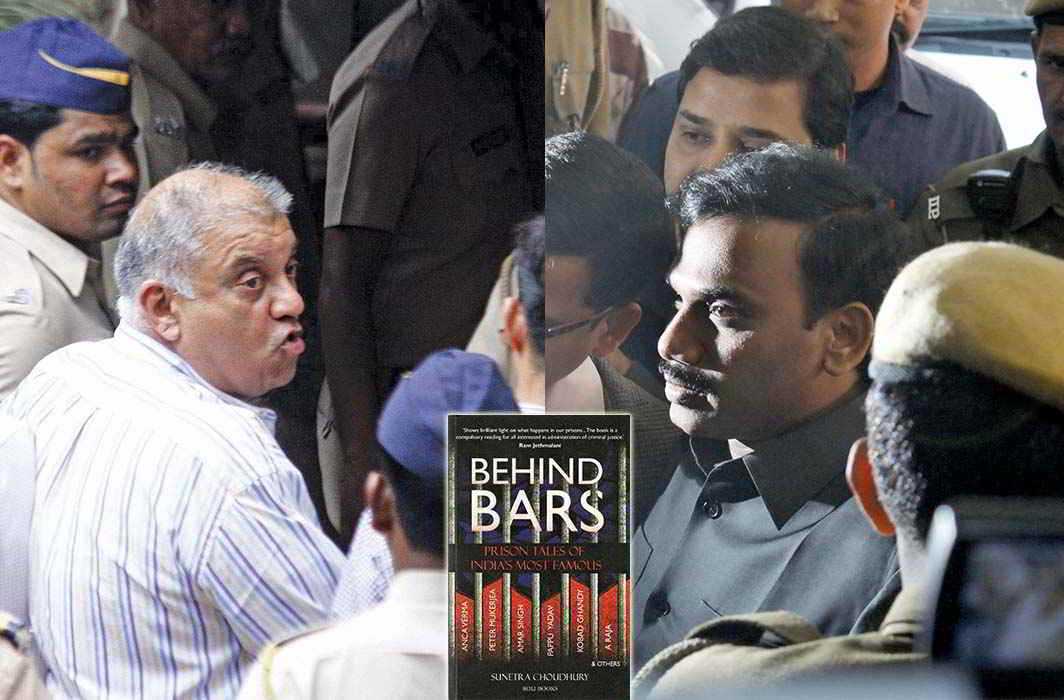

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]These movers and shakers of the country have spent lives of glitz and glamour, rubbing shoulders with others in similar positions of power. But they have also experienced hellish conditions in Indian prisons. Sleeping on floor, eating prison food and surviving on meager monthly expenses, they have been there, done that. NDTV journalist Sunetra Choudhury, in a one-of-its-kind book, has brought to us their life behind bars. Extracts:

THE RAJA WHO WAS BANISHED

A Raja, former telecom minister, arrested for his role in the 2G scam

The jail experience of a regular inmate and a VIP is never comparable. Ward Number 9 in which he (Raja) was staying was the very same one that Indira Gandhi was also kept in 1978. There were only five cells in that ward and a separate kitchen to cater to them. Each cell had two rooms, one sitting room and one bedroom. The bedroom had an attached bathroom with shower, washbasin and a mirror. The other occupants of this plush setting included Subrata Roy or Saharasri and a former minister from Haryana, Gopal Kanda. Of course, Subrata Roy also spent some of the time in a special jail which was the old court complex of Tihar. The complex had been converted into meeting rooms and conference rooms for Roy and his associates to conduct their business, and that was with the permission of the Supreme Court. Of course, the fact that these meeting and conference rooms were air-conditioned and had a telephone connection and internet facilities, caused a lot of heartburn among all the other high-profile inmates.

Raja may not have had the court-sanctioned digs that Saharasri enjoyed, but he too had the entire jail staff at his beck and call. The only luxury they couldn’t have was an air-conditioner in their cells, but as Raja was a high-security prisoner, he could spend his day in the jail superintendent’s office which was air-conditioned. At any rate, their cells were privy to the luxury of a cooler. According to their security assessment, the 1.76 lakh crore tag meant that some common criminal could attack him in jail, and so if he needed to go around jail, he needed security. So they preferred him sitting in the superintendent’s office. If others were woken up at 5 a.m. and were served breakfast at 6.30 a.m., Raja had a jail orderly asking what they could get him from the canteen.

‘Only non-vegetarian food wasn’t allowed, but the food was delicious and we also had sweets and nariyal paani (coconut water)… from the canteen. Every day, someone would come and ask: “Sir, what would you like today?”’

Even if he ventured towards the library, Raja would have about five policemen following him. That is why the DG of Prisons and other officials gave him the provision to get all the 2G documents in his own cell. Not just that, he could also have the other 2G accused come into his cell, so that they could all work on it. Now, if you want to know why that is a big deal, you have to remember that when the CBI filed the charge sheet in court, they had to bring in seven trunk-loads of paper. So the jail permission meant that a rickshaw had to make several trips to jail to carry all the papers that were needed for these accused. And they were all stacked up along the corridors of their cells.

‘You have to understand. If they threw the jail book at me, then each and every paper would have to be cleared by the jail authorities, but they were very kind. I also never asked for unreasonable things, but this allowed us all to work together on the case even from inside.’

There was one allowance that Raja got in jail that he appreciated above all. In 2011, his daughter was a 13-year-old student at Mater Dei Convent. If there’s one person who was severely affected by his incarceration, it was she, because of the media’s incessant reporting about his case. Her school performance was severely affected, and from being a student who always got above 85 per cent, her marks dropped significantly.

It was at that time that the Tihar Jail officials relaxed all mulakat rules for her. They allowed Mayuri to visit her father at whatever time she liked after school and on any given day. The superintendent of police would give them space in his office to talk. The regular Tihar visitors would otherwise be waiting for their weekly meetings, which would take place over a glass partition with the help of headphones. Raja was grateful for these VIP allowances.

‘I am also grateful to the teachers of Mater Dei. They kept encouraging my daughter and telling her that this was a part of politics and that I would come out of it soon. They issued instructions to everyone in school that no one would say anything about me…’

Whether it is shepherding by the staff of the school or good fortune, Mayuri is now a confident student of law, just like her father.

THE CEO IN JAIL

Peter Mukerjea, media baron, accused in the Sheena Bora murder case

There are good days and bad days in captivity for all. On a good day… your bail application seems to have had a positive hearing from the judge. That same feeling doesn’t look so good when the hearing is adjourned and postponed weeks later, on a flimsy excuse. These ups and downs are captured in Peter Mukerjea’s notes from jail.

On 28 September 2016, here’s how he describes being in jail: ‘It’s like being in a spa—what can I say? No alcohol, no cigarettes, early to bed, early to rise, exercise for a couple of hours, lots of reading, plenty of time to think, no junk food—all very healthy. I’ve lost a few kilos—which is no bad thing and as I’m indoors most of the day, I don’t get too much sunlight so my skin has improved.’

But the mood is totally different just a month later in his note on 24 October: ‘Lock-up or jail is no “spa”. That was a tongue-in-cheek comment and I hope you understood that. My day in the outside world was again a normal routine—which included gym, exercise, catching up with friends, occasional golf, TV and catching up on my housekeeping details. All of the above are what I’m unable to do now. So it’s miserable, not fun and although it’s an experience, it’s not one that I would recommend to anyone. It’s pathetic. Jails are overcrowded and far from being a reform centre, they’re a grim reality check on life.’

The fluctuation of mood is not surprising. From being on the power list of business magazines, he was down to being on the criminal roll call at Arthur Road Jail. He was sleeping on the floor, next to strange people, with odd routine, barely a change of clothes. There were small mercies though like a permission from court to eat home food, which meant he still got fish to eat (‘it’s a diet designed to nourish than to be enjoyable!’). But as another Star News colleague Vidya wrote in a piece, in jail Peter was at the mercy of the whims of junior police officials. Despite the allowance from court for his meals, Vidya once caught the lockup police refusing to let him eat, insisting that he had to leave for Arthur Road Jail. That day, he went from pleading the police to the CBI officer to an absent judge, but he couldn’t get his lunch. That was one of the times he realized what a great leveller jail can be.

So what does a millionaire CEO learn in jail? Maybe, it’s about the lessons of simplicity, of enjoying the basics; in the midst of despair, finding someone to talk to and being appreciated. Sometimes Peter Mukerjea comes across as chatty and full of anecdotes, at others he says, ‘What happens in Rio, stays in Rio’.

Speaking of his ‘fellow-travellers’, Peter says: ‘We share experiences, laugh and try and make the most of the learnings, each of us have had. I’ve made some useful contacts and they’re mostly people I’d never have had the opportunity to meet, had I not been a guest of the “Govt of India” so I’m glad for that and it will make me a more circumspect person as a result. Some are incredibly rich and some incredibly poor and if I can, I will try and help those worse off than me. Everyone here has a common goal—to get out and not have to come back—so staying on the right side of the law is very important for most people I’ve met…. How long these new acquaintances last is something for the future, although it’s true to say that being in jail gives you a good understanding and realization of who your real friends are ….’

If there’s one thing any jail teaches a white collar man, it’s how to make do on an impossible budget. It’s one of the first things that Peter says he learnt. ‘The economy within the jail is unique given there’s no cash—but a really effective barter system seems to work. Home-cooked food is a rarity and is therefore a prized possession for those that have it…. Necessity being the mother of… is a well trodden path here and adaptability and innovation is phenomenal. I get a monthly spending allowance of a princely sum of 2,500 rupees, which I get each month from home by money order and which is credited to my ‘tuck-shop’ account and I get to buy goodies with that—biscuits, nuts, mineral water and such like, but making that last the month is an incredible challenge. So when I get out, I’m going to look forward to existing on a pocket money of 2,500 per month and make do just fine.’

(Behind Bars: Prison Tales of India’s Most Famous, 266 pages, is authored by Sunetra Choudhury, published by Roli Books and priced at Rs 395)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Latest world news12 hours ago

Latest world news12 hours ago

Latest world news12 hours ago

Latest world news12 hours ago

Latest world news12 hours ago

Latest world news12 hours ago

India News12 hours ago

India News12 hours ago

India News3 hours ago

India News3 hours ago

Latest world news3 hours ago

Latest world news3 hours ago