[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Journalist Shazi Zaman digs up a mine of historical resources to delve into the psyche of the Mughal ruler in his book Akbar

By Meha Mathur

Mughal rule under Babur, Humayun and Akbar might be a distant era for us, 400 years later, but it suddenly seems so close to us as far as societal and religious concerns go. Socio-political aspects of Mughal life, which hitherto mattered to us more as facts in history textbooks, now appear in a new light as scholars dig up reams of literary sources and shed light on thoughts that occupied individuals’ minds—their worries, jealousies, whims and fancies. As also a liberal outlook.

Journalist and history graduate Shazi Zaman has now written a landmark novel—Akbar—for which he has relied on original sources of the era. The book is written in Devnagari, in dialects used at the time (predominantly Persian, Hindi, Rajasthani and Brij), making it a painstaking read. But it’s worth the effort for history enthusiasts. Coming from a history aficionado-journalist, who vouches that every episode mentioned in the novel is based on real-life incidents gleaned from works dating to Akbar’s era, including his confidante Abul Fazl’s Akbarnamah, the book is also an authentic biography.

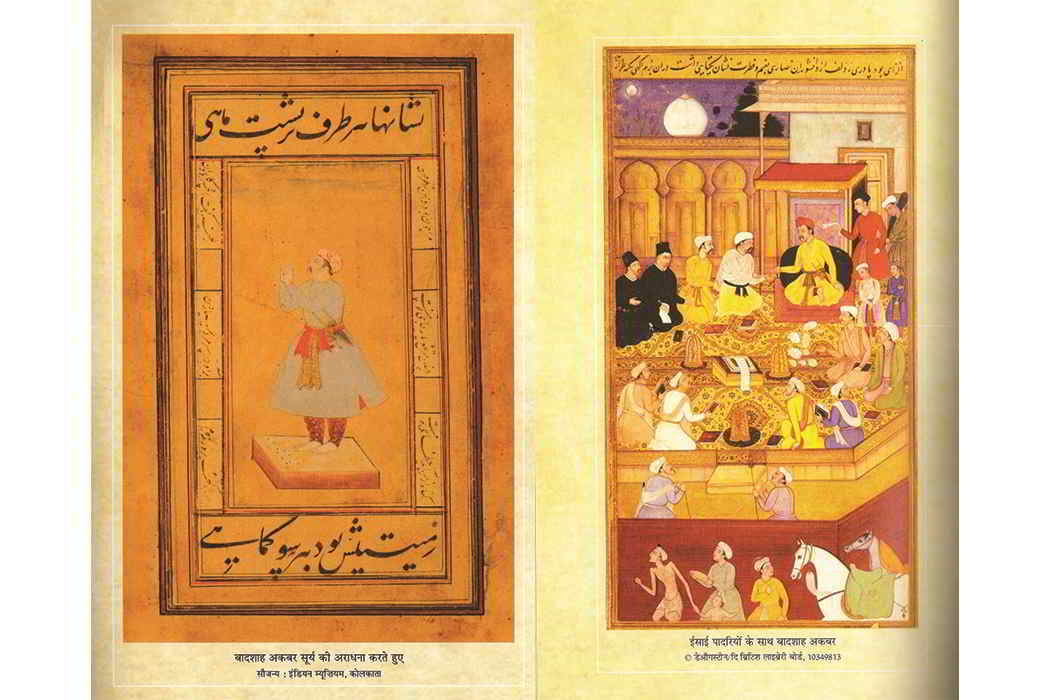

It’s another matter that like other emperors, Akbar, too, was touchy about his image and how future generations would perceive him. The author says: “Akbar was not just any emperor… he was a ruler who knew he was creating history. And he ensured how the future generations should look at this history. All the paintings in the tasvir khana—what we call Mughal miniatures—and royal buildings were done as per his wishes, and each and every word of Akbarnamah was written with his permission, and his perspective.”

Akbar’s quest to understand religion is the focus of the book. His impatience with Ulema, his keenness to understand the tenets of other faiths, his pampering of Hindu and Jain religious leaders and Christian preachers, much to the annoyance of Muslim clerics and even the Caliphate in Turkey, the futile attempts of Christian missionaries to convert him and his founding of Din-i-Illahi constitute much of the subject matter.

“The presence of so many faiths does not give me a moment’s peace. This outward paraphernalia weighs on me…. Acting with wisdom and discarding old ways is far better than the arguments of these lowly persons….. To be a Pir implies the ability to understand others’ pain and help remove it, not to grow beard, don a choga and create ruckus by debating worldly matters,” Akbar is quoted in the book.

On his instructions, an ibaadatkhana was constructed around the Anoop Talao (pond) in Fatehpur Sikri where Akbar started interfaith dialogues. He said: “I have called this majlis so that the truth of every faith—including Hindu faith—can be understood.” He was critical of Ulemas for being narrow-minded. “They think only those who read the Kalma, eat meat and do sajda (the ritual of bowing to touch the ground with one’s forehead) are Muslims. A Muslim is one who wages a Jehad within and overcomes his desires and anger, and follows the law.”

His impatience grew with time, and in his characteristic anger—his bad temper comes to light in this novel—he once yelled at an Islamic thinker Mullah Badayuni, “You are talking nonsense” when a debate lingered on without conclusion. On another occasion, he actually punched a person’s face when he got irritated. It was his close coterie of Abul Fazl, Tansen and Birbal which would calm him down, when the stress of handling religious issues became overwhelming.

“Dheere Dheere Dheere Mann, Dheere hi sab kuchh hoe (“calm down. Things can be accomplished gradually”, to translate roughly), counseled Tansen on one occasion.

Fed up of the Ulema, Akbar considered taking on the mantle of the religious head too. Mullah Abdul Qadir Badayuni, who has been extensively quoted in the book, wrote that Akbar could not bring himself to following the diktats of others. And that Akbar decided to read the khutba (which the Imams do), because he wanted to be seen as an authority on Islam.

In June 1579, he announced from the Jama Masjid in Fatehpur Sikri that he is next to no one not only in worldly matters but also in matters of faith. But the author describes how the emperor could not complete reading the khutba, and with his voice shaking, he let Hafiz Mohammad Amin complete the task.

Increasingly, he veered away from the Islamic fold, and contemplated starting a new faith absorbing elements from all religions. He took to sun worship—there are miniatures showing him performing the ritual—banned the killing of cows, issued orders that Christians be allowed to build churches and gave land grants to the Jain faith.

The Portuguese power was on the rise already and making its supremacy felt on the seas vis-à-vis the Mughals. In this backdrop, a delegation of three missionaries arrived in the Mughal court and spent considerable time in the close company of Akbar from 1580 to 1583. They were invited to all the religious discussions, annoying the Ulema even further. The author spends considerable space on describing the single-minded efforts of the clergymen to convert Akbar, and of Akbar’s openness to understand Christianity but his antipathy to conversions. He started his second son Murad’s education under the tutelage of these missionaries; the princes got a fair exposure to these missionaries.

The frustration of the clergymen at failing to convert Akbar is obvious. Missionary Rudolf Aquaviva wrote in a letter that the emperor viewed everything with suspicion, and applied his mind to matters of faith too.

But it was the approach of the 12th-century thinker, Ibne Arabi, to religion that Akbar came to imbibe. Arabi believed that just as water takes on the colour of its container, similarly, God is seen in every form and every individual. And if human beings understand this thing, they will not find fault with other faiths.

But was Akbar rational to the core? For, how could a person, who despised the narrow-mindedness of the Muslim cleric, encourage sajda and make the cream of his durbar, Birbal and Abul Fazl, bend before him to gain entry to his faith Din-i-Illahi? In fact, Akbar wanted the entire durbar to perform sajda but the Ulema created a furore. How could he replace the Hijri calendar (Islamic calendar) with Illahi calendar, which began with the date of his ascension to the throne? How could he give most brutal punishments to his detractors?

Anecdotes relating to miracles associated with Akbar gained currency during this time, like a passerby in a jungle coming face to face with a lion, and, upon uttering Akbar’s name, escaping death.

“Badshah Salaamat is saal paigambari ka daawaa karenge.

Ghar Khuda ne chaha toh woh agle saal khuda ban jaaenge”.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Mullah Sheri, a murid of Akbar wrote these flattering lines; such was the mood among his followers then. But not everyone could be convinced. Man Singh, a jewel in Akbar’s durbar and related to the emperor by marriage, bluntly refused, saying: “If being your murid means sacrificing my life for you, I am all willing. But if it means something else, well, I am a Hindu. If you order me, I will become a Muslim, but besides that I am not aware of the existence of any other religion.”

Nor could Akbar impress the Bhakti saints and poets of his times. The land of Krishna, Brij bhoomi, was not far from Fatehpur Sikri, and Akbar, on his visit to Surdas, requested that he sing in the emperor’s praise. Surdas refused, saying there was no place for him in his (the poet’s) heart. And Vaishnav poet Govindswami got angry when he realised that the emperor was sitting in the audience, and said his Raaga had been rendered ineffective by Akbar’s presence.

But the book is not just about matters of faith. Kingship, kinship, conquests and assimilation are some other prominent themes. Jealousies and scramble for power between brothers and half-brothers are other prominent strands.

Part one of the book deals with the expansion of the empire, and traverses three generations—Babur, Humayun and Akbar. The author traces the Mughal genealogy to Chengiz Khan and Taimur, describes how Babur first established a foothold in India, the wars that he and Humayun faced, the defeats that Humayun suffered and his travails while in exile.

Part two of the book, while dealing with Akbar’s experiments with faith, has many other facets of imperial life. How marriage alliances with Rajputs helped further Mughal interests; how kings were particular about paying visits to elderly ladies of the family, including step-mothers, sisters and step-sisters; how they gave importance to sons’ education; what games they played (Akbar was very fond of pigeon fights and derived great joy in taming out-of-control elephants); their attire; food (for example Akbar ate only once a day, when he felt hungry); their lingo (Akbar was also prone to abuses on occasions), are other interesting aspects that come to light.

The emperor’s equations with his sons are also well elucidated. While Akbar had to suffer the pain of his son Salim’s revolt and of his two other sons Murad and Daliyal dying of alcoholism, Salim had to bear the heartbreak of son Khusro going wayward. In grief, Salim’s wife and Khusro’s mother Shah Begum committed suicide, leaving Salim further distraught.

Salim was later married to Mani Bai, daughter of Jodhpur’s ruler Udai Singh. She came to be called Jodha Bai after Jodhpur. The book sets at rest the controversy stirred by the movie Jodha-Akbar a decade ago.

But the most startling episode that comes to light in this book is a strange mental state Akbar’s close associates found him in one night during a royal hunting expedition across Jhelum. This episode has been described by Abul Fazl in Akbarnamah, Mullah Abdul Qadir Badayuni in Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh and Dalpat Vilas in his work. “Gai hai su Hindu Khavo. Aur Musalman suvar Khavo…,” Akbar was yelling. Was it a case of temporary epilepsy or bipolar disorder, the author questions, as he sets the tone for the book with this episode.

The urgency to incorporate many details in the narrative shows, especially in the first part of the book. Constantly going back and forth between the three generations doesn’t help either, for there’s the risk of the reader losing the thread. Also, the choice of language and the reference to all the titles and epithets prevalent then makes for a tough reading: Babur is referred to as Firdaus Makaani, Babur Badshah or Zahiruddin Mohammad Babur throughout the book; Humayun referred to as Jannat Ashiyani, Humayun Badshah or Nasiruddin Mohammad Humayun throughout. But the understanding of the issues that Zaman displays makes for a perfect tribute to his “ustaad”, late Mohammad Amin, who taught him Mughal history at St Stephens College.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Lead images: Miniatures sourced from the book. (Left) Akbar worshipping the Sun; (right) Akbar with Christian missionaries. The images were originally sourced from Indian Museum Kolkata, and The British Library Board, respectively[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Akbar

Writer: Shazi Zaman

Publisher: Rajkamal Paperbacks

Price: Rs 350[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

India News24 hours ago

India News24 hours ago

Latest world news24 hours ago

Latest world news24 hours ago

Latest world news9 hours ago

Latest world news9 hours ago

Latest world news9 hours ago

Latest world news9 hours ago

India News9 hours ago

India News9 hours ago

Latest world news9 hours ago

Latest world news9 hours ago

India News9 hours ago

India News9 hours ago