Book reviews

A grotesque tale of the isolated and disregarded

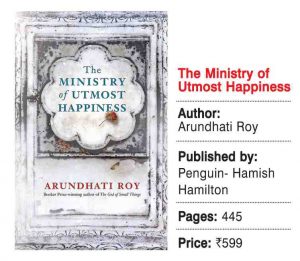

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Arundhati Roy’s second novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is utopian and crammed with intense antagonism. It exposes the difficult times we live in and manages to shake us out of our comfort zone

By Binoo K John

These are dystopic times. If it’s not noir, it’s not a novel. Everywhere there are graveyards and people are dying or on the verge of death. This year’s Palme D’Or at Cannes went to Swedish director Ruben Ostlund’s The Square which Time magazine describes as “a sly sardonic picture about a dashing museum curator whose dysfunctional institution is a microcosm of the larger world… What does it take to jog the upper classes out of their comfortable insularity?”

In fact, the job of a novelist is the same as that of a filmmaker and the sooner he/she can rattle various classes and castes out of the insularity, the better. But pulling people out of their comfort zone is a tough creative act. Far away from the film festival circuit, another novel based in the South Kerala coast written by the up and coming Anees Salim and published this month by Penguin-Hamish Hamilton— the same publishers of Arundhati Roy (Is June the dystopia month to outgun the cruelty of April?)—also envelopes us in a dark sad world in which one of the main character is dying, dying, almost dead, wakes up from the dead, goes for a walk on the beach and finally dies again with a flourish which has a finality to it.

Anees Salim also loves the graveyard like Arundhati Roy. His graveyard appears unsurprisingly after the casual flip of the first page of the deceptively titled The Small Town Sea. To quote: “The graveyard Vappa was taken to was an unruly garden, carpeted with a thick layer of dead leaves. I had been there before… the undergrowth was like Pygmies jungles, studded with thorns as if they were guarding the dead from the living.” The graveyard appears again a bit later as if to confirm the finality of various deaths.

June being the month of dystopia, the master of them all, Arundhati Roy arrives with her own graveyard, (cruel joke to take us to a graveyard after we waited 20 years to read this and with the gleefully ironic words “Utmost happiness” in the title) which is also like the Swedish film—a microcosm of a larger world.

Roy’s graveyard has no match in recent memory. Mainly because this Nizamuddin (where this writer goes to buy beef more as a sign of rebellion than craving!) graveyard is also a place to live, not just to die. Right there on page one, the graveyard comes alive. “She lived in a graveyard like a tree. At dawn she saw the crows off and welcomed the bats home. At dusk she did the opposite. Between shifts she conferred with the ghosts of vultures that loomed in her high branches.” Some writers like Salim look at the undergrowth and others like Roy look at the high branches. Some graveyards are for the dead. Others for the living.

Roy’s novel betrays the burden of expectation, the burden of portraying an India that some of us like the author believe is getting ruptured by hate lines, the burden of drawing out a metaphor for this regressing country, the burden of standing up to all that, the burden of having changed journalism into a sword that she twisted into the rib cage of various governments, the burden of standing alone, a waif of a girl against everything, with only the power of her intellect, the unflinching daring and total mastery of the language to sustain her.

In terms of polemic and sarcasm and the big sword that she pierces into the heart of the ruling establishment, nothing has been written in India to match this

Utmost Happiness at various stages, burdened by unrelenting polemic, almost sinks (which would have left us with Utmost Sadness) with the weight of drawing out this India, but the power of Roy’s intellect, her felicity with language, the ease of her sarcasm and bitter ironies all hold up the novel and sets it up for another shot at the Booker.

From page one it jogs us out of our comfort zone, takes us from the graveyard of Nizamuddin to the graveyards of Gujarat, of Kashmir as if the darkness of a hijra’s world with which the book starts wasn’t enough. At the release of the Italian edition of the book in Rome which this writer attended, Roy said that boundaries run through all the characters in her book. The Hijra Anjum of course crosses the boundaries of gender, her friend Saddam Hussain the boundaries of religion, a Hindu having taken on the Muslim identity, Kashmir of course not knowing where its boundaries lie and so on. (“In Kashmir when we wake up and say ‘Good morning’ what we actually mean is ‘good mourning’”) The novel thus exists in the cusp of being and nothingness. Through it all Roy trolls the undergrowth so to say, scooping up the dregs of society trying to give them a name and a meaning.

From page one it jogs us out of our comfort zone, takes us from the graveyard of Nizamuddin to the graveyards of Gujarat, of Kashmir as if the darkness of a hijra’s world with which the book starts wasn’t enough. At the release of the Italian edition of the book in Rome which this writer attended, Roy said that boundaries run through all the characters in her book. The Hijra Anjum of course crosses the boundaries of gender, her friend Saddam Hussain the boundaries of religion, a Hindu having taken on the Muslim identity, Kashmir of course not knowing where its boundaries lie and so on. (“In Kashmir when we wake up and say ‘Good morning’ what we actually mean is ‘good mourning’”) The novel thus exists in the cusp of being and nothingness. Through it all Roy trolls the undergrowth so to say, scooping up the dregs of society trying to give them a name and a meaning.

Roy’s focus no doubt are the forgotten underdogs of society whom the emerging India has pushed to the margins and is making an effort to forget them as well. “Their stories are being erased. Even in Bollywood their stories are no longer told,” Roy says.

Brimming with anger, Roy’s novel is completely scatological as well, liberally using the words forbidden by the moral classes that dominate today’s discourse, as if to dare them. Even the bright yellow Amaltas flower that blooms in Delhi says “fuck you” to the sky over and over again.

In many sections, the novel reads like an extension of her powerful polemical essays which for the last two decades send shivers down the spine of the political class who like draughtsmen were drawing out the details of the police-CBI-military raj to replace the license-permit raj which we all despised and threw away. “The violence of exclusion and the violence of inclusion is part of the Indian project,” she says.

The novel is a parade of the unwanted and the forgotten. Roy builds up for us an India we have almost forgotten in our rush to catch up with the GDP numbers and the Repo rate. We have used whiteners over the scripts of the unwashed, Roy seems to say and offers us this novel spilling with vitriol and sadness. (Why else would the copy I got be wrapped with two jackets, as if to contain all the acid within?)

Brimming with anger, Roy’s novel is completely scatological as well, liberally using the words forbidden by the moral classes that dominate today’s discourse, as if to dare them. Even the bright yellow Amaltas flower that blooms in Delhi says “fuck you” to the sky over and over again. In case the western reader fails to understand all the Delhi gaalis that liberally italicise the text, the author gives the translation as well, which considerably helps those like this author who use these words on the streets and the parlours of Delhi without really understanding their underlying mysteries.

In 2011, Hazare went on an indefinite fast to push for the passing of the Lokpal bill. Photo: Anil Shakya

In terms of polemic and sarcasm and the big sword that she pierces into the heart of the ruling establishment, nothing has been written in India to match this. Jantar Mantar, Nizamuddin and Old Delhi are her favourite hunting grounds. Roy goes to Jantar Mantar to completely demolish Anna Hazare and Kejriwal (Aggarwal in the novel) for what the author terms a pretend war against corruption. “Like a good prospector the old man had tapped into a rich seam, a reservoir against public anger and much to his own surprise had become a cult figure overnight.” To Anna she credits part of the middle class sense of entitlement and anger against the underclass which sustains many governments in India today. “Doodh maangogey to kheer dengey! Kashmir maangogey to chiir dengey!”

A Booker winner is entitled to take this majestic leap of faith to create a modern-day classic. Too many complications and complexities, the product of such ambition, destroy the flow of the book. Much of the stuff could have been done away with but which editor can suggest this to Roy without being put down?

Roy sees Delhi as very few have, and big novels are set in big cities. She sees the city as an evolving story. As a modern Indian novel in English, (most Indian novels are set in various comfort zones so as not to disturb its target audience) for its scale, its understanding of the larger hidden Indian story, its complete empathy with the underclasses, its utter scorn for the pot bellied ruling classes and their devious take-over schemes, the book is a classic. With this and some earlier novels, we can hope that the Indian English novel is finally liberated from, the concerns of the ruthlessly greedy middle class.

Few novels I have read or read about, have so totally identified with the deprived and the sad. Was she telling the unseen or telling the stories we refuse to see? Either way, Roy has given us a masterpiece to talk about for many years. If not anything, we all need to feel angry for a lot of things.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Book reviews

The Sattvik Kitchen review: Relook at ancient food practices in modern times

If you are the one looking to embrace healthy food habits without compromising on modern delicacies, then this book is a must read!

The cacophony of bizarre food combinations across the streets of India has almost taken over the concept of healthy food practices. Amid this, yoga guru Dr Hansaji Yogendra’s The Sattvik Kitchen, published by Rupa, is a forthright work that takes you back to ancient food practices and Ayurveda.

As the subtitle reads, The Art and Science of Healthy Living, the book endows a holistic approach to ayurvedic diet along with modern evidence based nutrition. From Basil-Broccoli Soup to Sprouted Green Gram Salad and Strawberry Oats Smoothie to Mixed Dal Parathas, the book not only provides you with the recipes but also stresses on healthy cooking tips together with nutritional benefits.

Besides, Dr Hansaji Yogendra’s book emphasizes on the traditional methods of food preparation and the advantages of using traditional cookwares like iron and copper vessels. The narrative portrays a balanced approach, knitting traditional wisdom with contemporary scientific understanding.

The author, through her book, sheds light on the principles of Ayurveda and highlights the metamorphic potential of adopting ancient food practices. She explains how our body reacts to food in terms of timing, quantity, manner of consumption and seasonal considerations. The book adeptly reintroduces ancient home remedies tailored to address various contemporary health issues.

Dr Yogendra, in her book, decodes the importance of nutritional knowledge to optimize both immediate and long-term health outcomes. It provides deep insights to understanding the intricate relationship between food choices and overall well-being, weaving Ayurveda with practical perception.

The book not only celebrates food philosophy but also offers a practical view into weight loss, well-being, and the profound impact of dietary choices on both physical and emotional aspects of our lives.

If you are the one looking to embrace healthy food habits without compromising on modern delicacies, then this book is a must read! The book is a roadmap to navigate the challenges of the modern day kitchens.

Book reviews

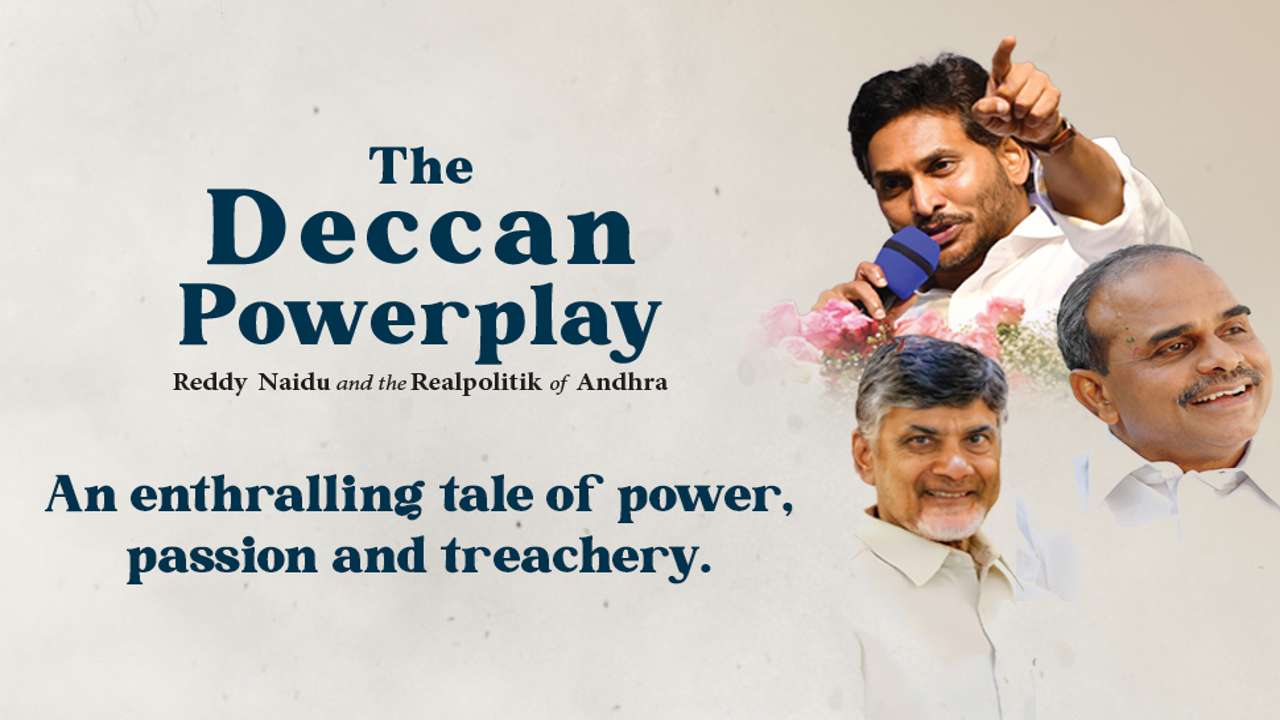

The Deccan Powerplay review: Bashing Chandrababu Naidu and his legacy

Amar Devulapalli’s book The Deccan Powerplay cornersthe TDP strongman with every petty incident exaggerated a la Baahubali

Mike Marqusee’s War Minus The Shooting is a seminal book on cricket and its influence on culture and politics in the Indian sub-continent during the 1996 Cricket World Cup. Amar Devulapalli’s book The Deccan Powerplay, published by Rupa, sounds like a similar exercise with its clear subtitle, “Reddy, Naidu and the Realpolitik of Andhra Pradesh“. The ambitious sounding subtitle crumbles under the weight of belied expectations of a scholarly treatise on the political interplay between the Reddys, the Kammas and the erstwhile united Andhra Pradesh. One can blame it on one’s own hopes and excuse the author of the lapse since the book has just three people to discuss: YS Rajsekhara Reddy, N. Chandrababu Naidu and Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy.

The chief protagonists here are YSR and his son, the incumbent Chief Minister of bifurcated Andhra Pradesh, Jagan Mohan Reddy. The lone villain, and one crafty as a fox if ever there was one, is Chandrababu Naidu. The book devotes a chapter to the corruption cases against Naidu, for which he was arrested in September 2023.

In crafting the narrative, the other heavyweights of Telugu country are discussed in passing, as peripheral players. N.T. Rama Rao does get the starring role, as befits the Telugu star of yesteryear and the founder of the Telugu Desam Party. But even this is fleeting. The Congress, which ruled the state till bifurcation, is portrayed as a faction-infested animal — so what if YSR stayed in the party both as loyal soldier as well as a seasoned yet dynamic general?

The book sets out to demolish the halo surrounding Naidu as the man who brought Information Technology majors to Hyderabad, nay Cyberabad, by beating Bengaluru. His breaking with NTR is depicted as a shrewd, calculated gambit to displace the TDP founder, who was also his father-in-law.

The book is replete with this and more Naidu nitpicking. Naidu took no bullshit from politicians or journalists. He gave it back to the scribes when needed, apart from his favourite media groups, one of the reasons they were not very happy kowtowing to him,

as the book suggests. Instead they would make ostentatious bows to any political alternative merely for being less brusque than the now-out-on-bail former CM.

The book picks apart every claim Naidu ever made and portrays him as an opportunist. The problem with this is possibly because Naidu preceded Jagan Mohan as the rump AP’s last CM and had presumably used every trick in his arsenal to discredit the younger contender.

With Assembly elections due this year, this book reads like a party pamphlet and comes across as a political weapon among the undiscerning. An Instagram handle could have been more useful to this end. But for such a grandly-titled book: the anticlimax is swift and painful.

Book reviews

Fawaz Jaleel’s Nobody Likes An Outsider wins India Prime Authors Award

Indian thriller author, Fawaz Jaleel’s Indian political thriller, Nobody Likes An Outsider hit the market in March 2021. The book has been receiving rave reviews from both readers and critics since its release. Now, the book has got another achievement in the form of Foxclues India Prime Authors award.

Set in Begusarai, Nobody Likes An Outsider traces the death of a young Indian politician and his personal assistant. A young CBI team led by Yohan Tytler is called to investigate the murder. The book travels between 1970’s to 2020 across significant events that took place in the modern history of India and Bihar. The climax reveals a very sensitive yet lesser spoken about aspect in Indian politics and demographics.

This is Fawaz Jaleel’s debut novel. However, he has written three short stories in the past – From The Land Of Palaces, The Legend of Birbal’s Bull, and Alternate Identities. These stories were published in anthology books by Write India publishers and Juggernaut.

Foxclues received more than 3000 nominations for the award out of which Nobody Likes An Outsider made the cut. The book has also been optioned by a Mumbai based production house to be converted to a series. Presented by delhi-based publishing house, Kalamos, Nobody Likes An Outsider continues to attract a good readership.

Born in Vilakkudy Kerala, Fawaz Jaleel did his schooling in the island nation of Bahrain before moving to Chennai for his post graduation. He completed his graduation in Journalism from Madras Christian College and post graduation in Development studies from Azim Premji University.

The sequel of Nobody Likes An Outsider is set to be released in 2022. Currently, Fawaz is working on another political thriller series based on geopolitical events with a focus on Indian politics. He also has a comedy-thriller about India’s housing market set to be released in the coming year.

-

Cricket news24 hours ago

Cricket news24 hours agoTelugu superstar Mahesh Babu meets SRH captain Pat Cummins, says it is an absolute honour

-

2024 Lok Sabha Elections24 hours ago

2024 Lok Sabha Elections24 hours agoMallikarjun Kharge writes to PM Modi seeks time to explain Congress’s Nyay Patra

-

Trending22 hours ago

Trending22 hours agoSocial media user shares video of Air India ground staff throwing expensive musical instruments, video goes viral

-

2024 Lok Sabha Elections7 hours ago

2024 Lok Sabha Elections7 hours agoPM Modi calls for high voter turnout in second phase of Lok Sabha elections 2024, says your vote is your voice

-

2024 Lok Sabha Elections1 hour ago

2024 Lok Sabha Elections1 hour agoLok Sabha election 2024: Nearly 50% voter turnout recorded in second phase till 3 pm

-

India News6 hours ago

India News6 hours agoSalman Khan house firing case: NIA interrogates arrested shooters Sagar Pal, Vicky Gupta for three hours

-

2024 Lok Sabha Elections5 hours ago

2024 Lok Sabha Elections5 hours agoLok Sabha elections 2024: 102-year-old man walks to polling booth to cast his vote in Jammu