[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]A group of destitute farmers from Tamil Nadu are on a now-month-long hunger strike at Jantar Mantar in Delhi, demanding loan waivers, water for their fields and a little mercy. APN spoke to some of them, through their leader Ayyakkannu

By Meha Mathur

Skeletons of abject apathy cry on the streets of the national capital today. They scream to meet the Prime Minister, but when you can’t provide the threat of 50,000 tractors entering Delhi to clog the streets, as the Jat agitation did to push for reservation, your PM might as well be living in another land.

Thus is the fate of starving farmers from Tamil Nadu, a state in deep drought. Thus is the state of people who have nothing but the skeletons of their loved ones to show, just for a little mercy.

Damodaran, from the Nagapattinam district of Tamil Nadu, says he had taken a loan of Rs 4.5 lakh to buy a tractor. He managed to replay Rs 3.5 lakh. But then, he says, he suddenly saw his accumulated due, including interest, had jumped to a mammoth amount that was completely beyond his capacity to pay.

Faced with constant threats, his wife committed suicide. Damodaran has brought a skull, claiming it to be that of his wife’s, to a protest hunger strike in the Capital, a blunt reminder to the government that achche din can’t be claimed in a bubble of words.

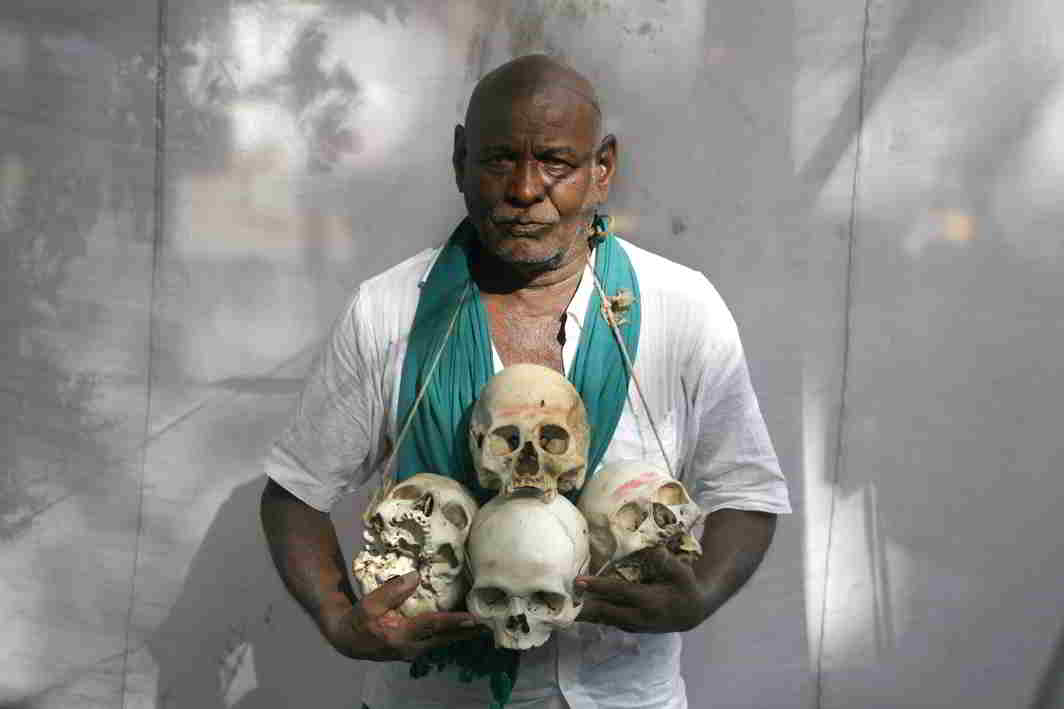

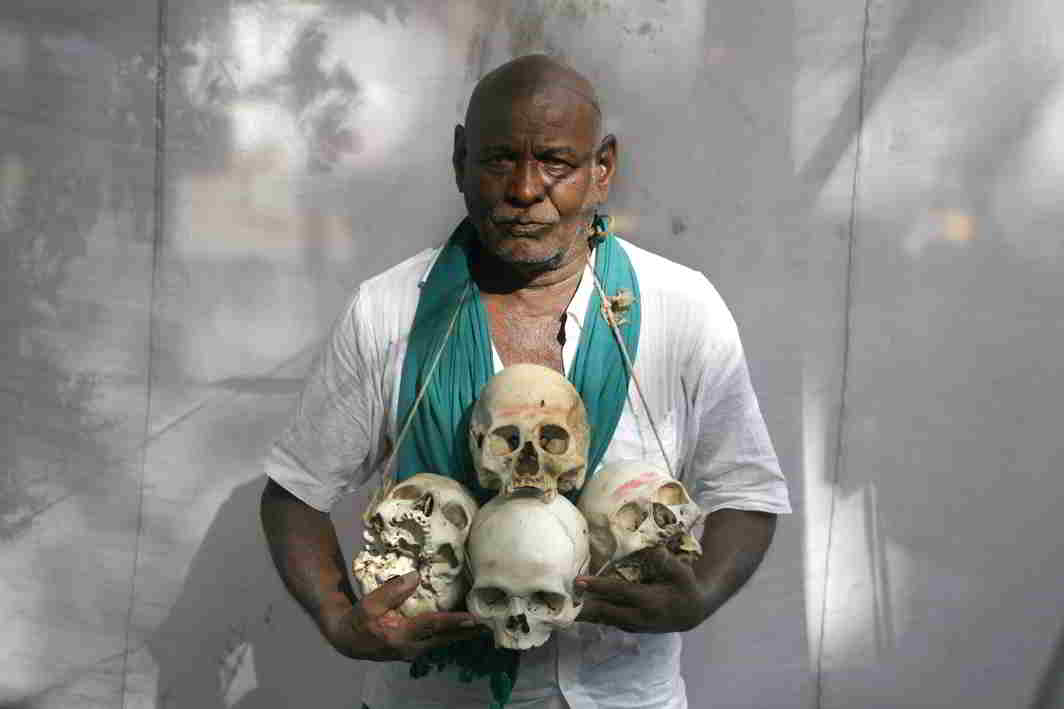

DIRE STRAITS: A distraught farmer narrates his misfortunes during the stir

One hundred and seventy four farmers had joined the protest mid-March. They begged and borrowed Rs 2,000-5,000 from relatives and friends and even sold jewellery to finance their Delhi trip to join the protest, in the hope of getting justice. They also want their honour and respect restored. They say that banks, in trying to extract the loan amount from them, resort to the most humiliating tactics—like questioning where they get the money to buy clothes when there’s no money to repay loans. Stripped of all dignity, these farmers have decided to come in bare minimum attire, to try and shame those in government.

On April 10, a few farmers stripped near the PMO, when they had gone to present a memorandum of their demands to the Prime Minister and were denied audience.

Many have been forced to go back as because money dried out, or as they fell ill. But even now, 23 farmers continue with their hunger strike. Occupying a sizeable portion of the protest street at Jantar Mantar. They have been visited by politicians (such as Rahul Gandhi), environmentalists like Vandana Shiva as well religious figures. They are here to bring to government and media notice their dire condition.

Two small victories did happen. First, with the Madras High Court directing the state government to waive loans and secondly a central drought grant that has just about surfaced.

The root cause

The crisis is primarily on account of a severe water shortage. It hasn’t rained sufficiently in the last 10 years, and the Cauvery water dispute is very real to these farmers, receiving so little of an already drying river that both Tamil Nadu and Karnataka desperately rely upon, that it never really is enough.

AT THE HELM: Ayyakkannu, the leader of the stir

Ayyakkannu, a big farmer and a lawyer, who is leading this protest, informs that such a severe drought had not happened in the last 140 years.

The crops of paddy, banana and sugarcane, which are as such water intensive crops, are failing and are no more profitable. Four-hundred farmers have committed suicide. He informs that Tamil Nadu had demanded Rs 2,600 crore from the central government as input subsidy, out of which Rs 1,748 crore has been given.

Of the total relief fund of Rs 1,712.1 crore announced for Tamil Nadu recently by the Centre, 1,447.99 crore is for kharif drought relief and Rs 264.11 crore for the destruction in the cyclonic storm Vardha.

The decision to provide relief under NDRF to both states was taken in the recent meeting of a high level committee chaired by Home Minister Rajnath Singh.

Ayyakkannu, 72, owns 20 acres of land and is also a lawyer specializing in criminal law. He has handled 200 to 300 cases and, strangely enough, 5,000 related divorce cases. He says he was moved when individuals started coming to him seeking divorce because the partner has not been able to repay bank loans and life has become hell. Their pathetic condition led him to start a farmers’ association and he decided to take up his cases free of cost.

With 70 percent shortfall of rains in Tamil Nadu, the desperation is clear. The farmers had protested in front of the office of Trichy’s collector holding dead rats in their mouths in December 2016. The state government has already pressed the panic button. The then chief minister O Panneerselvam declared the state draught-hit on January 10, and the government requested the centre for a relief of Rs 39,565 crore from the National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF).

Education takes a hit

Akhilan of Trichy district got admission to first year BE at Annai Mathammal Sheela Engineering College, but when he approached the Bank of Baroda for an education loan, he was told that since his father, a farmer, had already taken a loan of Rs 1,75,000, which he had been unable to repay, the son could not be given any further loan. Akhilan had to surrender his seat. Frustrated, he even tried to commit suicide.

John Milkiyo Raj had taken Rs 4 lakh from the Bank of Baroda in 2007, and although he has paid back 2 lakh already, a huge amount (including interest) is still pending. The only recourse now is to sell off his land to repay. And Nachamma from Trichy, who had taken a loan of Rs 3 lakh for a bore well on her seven-acre land in 2012, could repay only R 1.5 lakh, and still has a huge amount pending against her. Her jewels have been auctioned, including the mangalsutra. Today, her husband is working as a watchman for a salary of Rs 2,500 per month, and her two married sons, unable to sustain themselves on farming returns, are working as railway porters.

THE SURVIVOR: A protester displays the skulls of his brethren who committed suicide

SR Kannan, a graduate in geography, took a loan of Rs 3 lakh from the Syndicate Bank and Rs 3 lakh from the Indian Bank, and since has pledged his jewellery, that has been auctioned. Now his worry is how to save his land from being auctioned too.

The river of hope

A strong notion that he and his fellow farmers harbour is that interlinking of rivers will somehow solve the problem. The environmentalists’ argument that it might create havoc with nature is lost on them. Ayyakkannu says: “The water resource ministry has examined the proposal and said it was feasible. But no steps have been taken so far.”

D Davidraj, a graduate in history and young farmer from Kanyakumari, also feels that interlinking of rivers between north and south India can solve the problem as “north India has a lot of water”. Davidraj owns a five acre banana field, and has also suffered due to paucity of water. The first time that he cultivated banana, he got good returns, and invested that in the next season. But then the rains failed. Now, the still-optimistic youngster sits flanked by his friends, among them an IIT-Kharagpur graduate, who points out how drastically the water level has fallen, from 130 feet to 270 feet. He also points out how, while the government is letting the powerful multinational Pepsi draw excess water in Tirunelveli, commoners adjacent to it are facing extreme hardship.

As a matter of fact, in March this year, a Madras High Court bench in Madurai dismissed a clutch of petitions against the supply of surface water of Tamirabarani to Pepsi and Coca-Cola at their plants in Gangaikondan in Tirunelveli, whereas in November 2016 the court had put an interim ban on co-packers of these two cold drink companies from using surface water.

A partial victory for the protesting farmers has been achieved, with the Madras High Court directing the state government on April 4 to waive loans of all farmers. In 2016 the state government had agreed to waive loans to small and marginal farmers owning land up to five acres (16.9 lakh farmers), but now an additional 3.01 lakh farmers have been brought into the ambit of loan waivers. This means that an additional burden of Rs 1,980 crore will now be incurred by the state, while the state had originally planned a loan waiver of Rs 5,780 crore.

The farmers now want a similar loan waiver from centralized banks, too.

It might be a big economic cost, but considering that 400 farmers have already taken their lives, it’s definitely worth the pain.

Photos by Anil Shakya[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Latest world news11 hours ago

Latest world news11 hours ago

Latest world news11 hours ago

Latest world news11 hours ago

India News11 hours ago

India News11 hours ago

Latest world news11 hours ago

Latest world news11 hours ago

India News10 hours ago

India News10 hours ago