[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

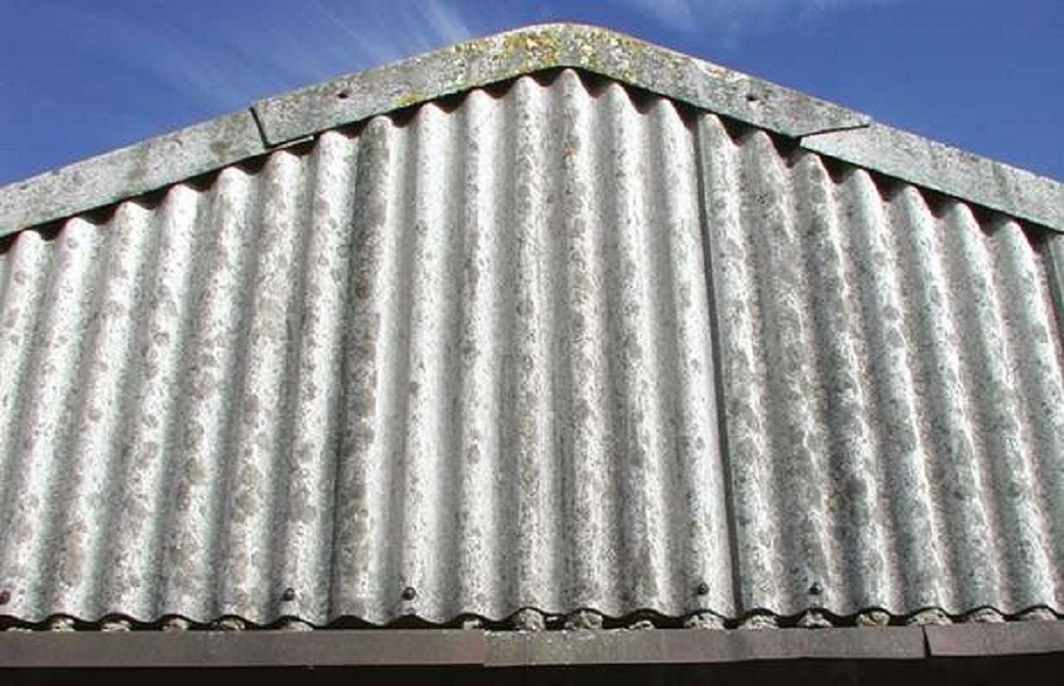

Cancer caused by merely inhaling an asbestos fibre is looming like an epidemic in developing countries, including India.

By Rashme Sehgal

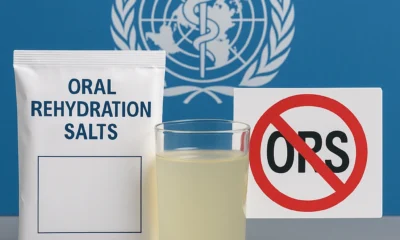

White Asbestos, also known as chrysotile asbestos, is a proven carcinogen that kills 30 people each day in India. The WHO has found it to be so carcinogenic that it has calculated that over 100,000 people die from exposure to it every year. Late Environment Minister Anil Madhav Dave had spoken out against its use and had demanded it be phased out.

The first step towards phasing it out is to have chrysotile asbestos defined as a hazardous substance, as has already been done by the World Health Organisation, the International Labour Organization and 31 scientist-members of the United Nations Chemical Review Committee.

So while the Central and some state pollution control boards have declared it to be a hazardous substance, the Central government has shied away from banning this toxic material.

This conflicting stand was reflected at the all-important Conference of Parties to the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm conventions held earlier this month in Geneva. These three meets — the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal, the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants and the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure of Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade — focus on protecting people from hazardous chemicals.

India’s has been a changing stand. In 2011, the Ministry of Environment had listed asbestos as a hazardous substance but today their stand remains ambivalent. This ambiguity is manifest amongst Indian representatives present in Geneva. While officials from the Ministry of Chemicals insist asbestos is not a toxic material, officials from the Ministry of Environment believe that asbestos should be put on the Prior Informed Consent List whereby exporting nations will have to seek consent from the importing country before they can send this material.

India is the largest importer of asbestos in the world and imports huge amounts of asbestos from Russia, Brazil, Kazakhstan and Zimbabwe. Officials of these countries are lobbying hard to insure this material does not get on the informed consent list. India’s neighbouring countries realise the danger of this material and Nepal is amongst 55 countries to have banned this toxic material in 2014 while Sri Lanka is in the process of phasing it out.

Sanjay Parikh, counsel for the Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology, notes that India is “importing 1 lakh metric tonnes of toxic waste in India. This is a dangerous trend since asbestos waste is being left in open landfills, where it can pollute both the atmosphere and ground water”.

Realising the gravity of the situation, the previous United Progressive Alliance government had introduced The White Asbestos (Ban on Use and Import) Bill, 2009 in the Rajya Sabha, but in the end, little was done to convert the bill into a law. The BJP had also promised to phase out the use of this toxic material but so far they have not moved in this direction.

The little research done within the country serves to confirm the fears of activists and of the medical fraternity. A study by two researcher-doctors at Delhi’s Maulana Azad Medical College says that deaths from asbestos-related cancers could touch one million in developing nations by 2020. Dr Sanjay Chaturvedi, one of the co-authors of this report pointed out that even if a single fibre is inhaled, it is capable of causing mesothelioma (cancer of the protective layers of the lungs) and that has been proved by epidemiological, clinical and experimental studies.

Dr TK Joshi, director of the Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health in Delhi’s Lok Nayak Hospital, warned that given the latency period for asbestos cancers, in another decade, we will witness a major cancer epidemic caused by asbestos, at a point when this disease is on the decline in industrialised countries. He explained that widespread use of asbestos started in India in the 1980s, but 22 million people in the construction industry have already been exposed to it.

The Indian medical fraternity cites as a warning the example of United Kingdom, where consumption of 1.6 million tonnes of asbestos had produced the country’s worst epidemic of occupation disease and death, leading it and other industrialised nations to put an end to its use.

But India, like other rapidly industrialising countries, is not collecting enough data on the morbidity and mortality coming from workplace diseases. Dr Joshi regretted that the number of workers exposed could easily run into millions and the inhalation of just one fibre is enough to trigger damage.

The Central Labour Institute in India finds that there is a 7.25 per cent of prevalence of asbestosis among workers in the country. The Central Pollution Control Board further confirms that many of the 80% of mesotheliomas cases occur in men exposed to mineral fibres in their workplaces.

Before the Geneva conference commenced a few days ago, Gopal Krishna, who heads the environmental group Toxics Watch Alliance, had personally met the late Minister of Environment Dave to emphasise before him the need for India to remain consistent in its stand, especially since his ministry had declared white asbestos a hazardous substance

Representatives of the different ministries participating in the meet will have detailed discussions on whether to include asbestos on the Prior Informed Consent list. Countries exporting substances on this list need to notify and get informed consent from the importing country before sending the materials across. Asbestos-exporting countries like Russia, Kazakhstan, Brazil and Zimbabwe are likely to do everything they can to stall the inclusion of asbestos in this list.

India’s stand at previous convention discussions reflects this dichotomy. In 2011, a representative of the environment ministry argued that it must be declared a hazardous material. In 2013, India opposed listing chrysotile asbestos as a hazardous substance. India has also resisted the inclusion of asbestos in the Prior Informed Consent list, citing lack of data

This ambiguity towards this material is manifest on the ground as well. The District Magistrate (DM), Muzaffarpur and the Bihar Pollution Control Board had ordered the closure of the Bishnupur asbestos plant on grounds of gross violations of environmental norms and concealment of health hazards. But despite these orders, and the locking of the front gate of the factory, the plant continues to operate from its back gate.

Despite the scale of damage it can cause, reporting on this subject remains scarce primarily because the incubation mechanism of this form of lung cancer is very long drawn out.

Asbestos has other side effects also. A study, cited on the Ban Asbestos Network of India website, entitled ‘Asbestos exposure and ovarian fibre burden’ quoted epidemiological studies suggesting an increased risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in female asbestos workers and increased risk of malignancy in general in household contacts of asbestos workers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

India News12 hours ago

India News12 hours ago

India News11 hours ago

India News11 hours ago

India News2 hours ago

India News2 hours ago

Cricket news1 hour ago

Cricket news1 hour ago

India News25 mins ago

India News25 mins ago