[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]As opposed to the polite Indian dawdle of the head when faced with the prospect of saying a hard no; the French do not dodge the opportunity of saying “mon oeil”

By Shailaja Paramathma

If you have never heard a French say “non,” you still do not know the finality which that one single word possesses. No in France means an absolute no. The nasal drawl of the “n” rings longer, almost threateningly, if you try to pursue the matter any longer. It is a no-go for further negotiation and it would be a mistake to assume that you could coax anything more from the other person once he has refused.

The argumentative French?

Why? Because before the French say no, they have discussed threadbare every possibility of an agreement and every aspect of the issue has already been viewed from innumerable angles. If Amartya Sen thought only an Indian could be argumentative, the French would have ardently argued the notion and won the discussion in the end.

Blame it on their education system or the fact that they work only 35 hours a week and get up to four weeks of paid holiday every year, but if you give the French a meaningful topic, you will in return get a solid and earnest discussion.

French philosopher René Descartes

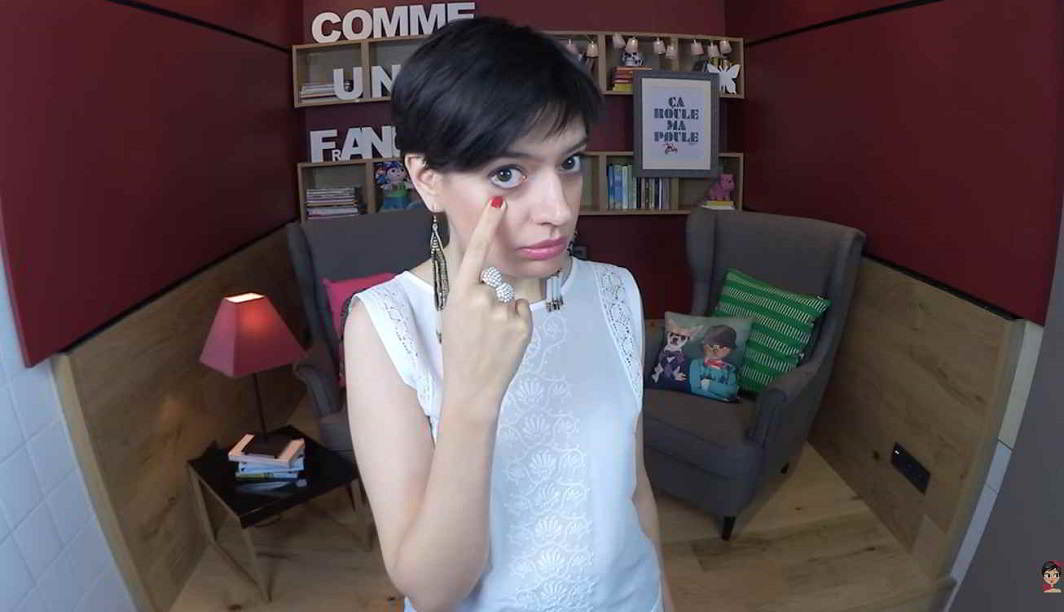

As opposed to the polite Indian dawdle of the head when faced with the prospect of saying a hard no; the French do not dodge the opportunity of saying “mon oeil,” literally meaning “my eye,” it’s equivalent in English being “my foot.” Mon oeil is an indignant refusal and is accompanied by pulling spitefully the lower lid of one’s eye with the index finger and glaring at the person responsible for provoking this reaction.

Past impedimenta

In fact in the French society, criticism delivered cold and hard is seen as a trait of intelligence in people and is much valued. René Descartes, the French philosopher and scientist, also known as the father of modern western philosophy wrote the famous quote of all time “Je pense donc je suis” translated into English as “I think, therefore I am” in his Discourse on the Method in 1637. The work addressed scepticism and the idea became central to the tenets of Western philosophy.

This “method of doubt” which said that the act of thinking about whether one existed was in itself proof that one did exist is applied in arguments by French people in their quest to find truth and knowledge. Making long-winding arguments, rationalising and taking time to stop and inspect all possible ways to a solution is a slow but a very addictive habit that the French possess.

The Cartesianism school of thought, as this movement came to be known later, gained sufficient popularity for the Church to label its followers as unorthodox and to oppose it. The theologian and philosopher Antoine Arnauld, one of the leading intellectuals of this philosophy is the writer of this very tongue in cheek line “Common sense is not really so common.”

Path to light

There is also the Lumières or Enlighteners in English, which was a movement that originated in France in the 18th century and soon spread throughout Europe. It rejected arbitrary authority, absolute monarchy as well as oppression on religious or moral grounds. They redefined the study of knowledge by fighting against irrationality, obscurantism and superstition. And put progress in art and science and the search for happiness high on their agenda.

The work of the Lumières had a great influence in the American Declaration of Independence and the French Revolution. The idea of the free individual, liberty for all guaranteed by the State and not decided on the whim of the government and backed by a strong rule of law are ideas that we still understand today and which were introduced to us by the writings of the Lumières.

Paris protests against Donald Trump

This intellectual and cultural renewal which aimed for the triumph of reason over faith and belief and the triumph of the bourgeois over nobility and clergy is something the French are still proud of.

Every year French students in their last year of “lycée” or Secondary school sit down to a Philosophy exam where they are expected to write lucid arguments in answer to questions like—“Can a scientific truth be dangerous?” and, “Is it one’s own responsibility to find happiness?” etc.

Examples worth following

Be it the French revolution in the late 18th century, when the French said no to monarchy or the student revolution of May 1968 which overturned the social order of the day, or the French labour unions that love to protest and say no when they do not agree with something. More often than not when the French take to the streets, they force their governments to pull up their socks and clean up their acts.

In personal life, even though using the word “no” too liberally can land you in conflict situations very easily, it is fair game if what you hanker after is a structured debate. Standing your ground is viewed by several cultures as a brave act and ideally requires self-discipline to be delivered well. It is also rumoured to save one’s time on unnecessary engagements and be more productive, though in the case of the French that last bit would be inapplicable.

Finally, what we need to be on the lookout for is—will the French not lose their gumption and say as definite a no to Marine Le Pen, the presidential candidate of the French National Front, a right-wing populist and nationalist political party, when they go to vote next month, as they did to Donald Trump when he was elected president of the United States. By May 2017 we should have the answer to that.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Latest world news15 hours ago

Latest world news15 hours ago

Latest world news15 hours ago

Latest world news15 hours ago

Latest world news15 hours ago

Latest world news15 hours ago

India News15 hours ago

India News15 hours ago

India News6 hours ago

India News6 hours ago

Latest world news6 hours ago

Latest world news6 hours ago