Book reviews

A grotesque tale of the isolated and disregarded

Published

9 years agoon

By

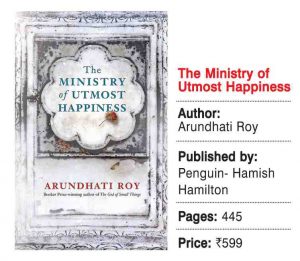

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Arundhati Roy’s second novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is utopian and crammed with intense antagonism. It exposes the difficult times we live in and manages to shake us out of our comfort zone

By Binoo K John

These are dystopic times. If it’s not noir, it’s not a novel. Everywhere there are graveyards and people are dying or on the verge of death. This year’s Palme D’Or at Cannes went to Swedish director Ruben Ostlund’s The Square which Time magazine describes as “a sly sardonic picture about a dashing museum curator whose dysfunctional institution is a microcosm of the larger world… What does it take to jog the upper classes out of their comfortable insularity?”

In fact, the job of a novelist is the same as that of a filmmaker and the sooner he/she can rattle various classes and castes out of the insularity, the better. But pulling people out of their comfort zone is a tough creative act. Far away from the film festival circuit, another novel based in the South Kerala coast written by the up and coming Anees Salim and published this month by Penguin-Hamish Hamilton— the same publishers of Arundhati Roy (Is June the dystopia month to outgun the cruelty of April?)—also envelopes us in a dark sad world in which one of the main character is dying, dying, almost dead, wakes up from the dead, goes for a walk on the beach and finally dies again with a flourish which has a finality to it.

Anees Salim also loves the graveyard like Arundhati Roy. His graveyard appears unsurprisingly after the casual flip of the first page of the deceptively titled The Small Town Sea. To quote: “The graveyard Vappa was taken to was an unruly garden, carpeted with a thick layer of dead leaves. I had been there before… the undergrowth was like Pygmies jungles, studded with thorns as if they were guarding the dead from the living.” The graveyard appears again a bit later as if to confirm the finality of various deaths.

June being the month of dystopia, the master of them all, Arundhati Roy arrives with her own graveyard, (cruel joke to take us to a graveyard after we waited 20 years to read this and with the gleefully ironic words “Utmost happiness” in the title) which is also like the Swedish film—a microcosm of a larger world.

Roy’s graveyard has no match in recent memory. Mainly because this Nizamuddin (where this writer goes to buy beef more as a sign of rebellion than craving!) graveyard is also a place to live, not just to die. Right there on page one, the graveyard comes alive. “She lived in a graveyard like a tree. At dawn she saw the crows off and welcomed the bats home. At dusk she did the opposite. Between shifts she conferred with the ghosts of vultures that loomed in her high branches.” Some writers like Salim look at the undergrowth and others like Roy look at the high branches. Some graveyards are for the dead. Others for the living.

Roy’s novel betrays the burden of expectation, the burden of portraying an India that some of us like the author believe is getting ruptured by hate lines, the burden of drawing out a metaphor for this regressing country, the burden of standing up to all that, the burden of having changed journalism into a sword that she twisted into the rib cage of various governments, the burden of standing alone, a waif of a girl against everything, with only the power of her intellect, the unflinching daring and total mastery of the language to sustain her.

In terms of polemic and sarcasm and the big sword that she pierces into the heart of the ruling establishment, nothing has been written in India to match this

Utmost Happiness at various stages, burdened by unrelenting polemic, almost sinks (which would have left us with Utmost Sadness) with the weight of drawing out this India, but the power of Roy’s intellect, her felicity with language, the ease of her sarcasm and bitter ironies all hold up the novel and sets it up for another shot at the Booker.

From page one it jogs us out of our comfort zone, takes us from the graveyard of Nizamuddin to the graveyards of Gujarat, of Kashmir as if the darkness of a hijra’s world with which the book starts wasn’t enough. At the release of the Italian edition of the book in Rome which this writer attended, Roy said that boundaries run through all the characters in her book. The Hijra Anjum of course crosses the boundaries of gender, her friend Saddam Hussain the boundaries of religion, a Hindu having taken on the Muslim identity, Kashmir of course not knowing where its boundaries lie and so on. (“In Kashmir when we wake up and say ‘Good morning’ what we actually mean is ‘good mourning’”) The novel thus exists in the cusp of being and nothingness. Through it all Roy trolls the undergrowth so to say, scooping up the dregs of society trying to give them a name and a meaning.

From page one it jogs us out of our comfort zone, takes us from the graveyard of Nizamuddin to the graveyards of Gujarat, of Kashmir as if the darkness of a hijra’s world with which the book starts wasn’t enough. At the release of the Italian edition of the book in Rome which this writer attended, Roy said that boundaries run through all the characters in her book. The Hijra Anjum of course crosses the boundaries of gender, her friend Saddam Hussain the boundaries of religion, a Hindu having taken on the Muslim identity, Kashmir of course not knowing where its boundaries lie and so on. (“In Kashmir when we wake up and say ‘Good morning’ what we actually mean is ‘good mourning’”) The novel thus exists in the cusp of being and nothingness. Through it all Roy trolls the undergrowth so to say, scooping up the dregs of society trying to give them a name and a meaning.

Roy’s focus no doubt are the forgotten underdogs of society whom the emerging India has pushed to the margins and is making an effort to forget them as well. “Their stories are being erased. Even in Bollywood their stories are no longer told,” Roy says.

Brimming with anger, Roy’s novel is completely scatological as well, liberally using the words forbidden by the moral classes that dominate today’s discourse, as if to dare them. Even the bright yellow Amaltas flower that blooms in Delhi says “fuck you” to the sky over and over again.

In many sections, the novel reads like an extension of her powerful polemical essays which for the last two decades send shivers down the spine of the political class who like draughtsmen were drawing out the details of the police-CBI-military raj to replace the license-permit raj which we all despised and threw away. “The violence of exclusion and the violence of inclusion is part of the Indian project,” she says.

The novel is a parade of the unwanted and the forgotten. Roy builds up for us an India we have almost forgotten in our rush to catch up with the GDP numbers and the Repo rate. We have used whiteners over the scripts of the unwashed, Roy seems to say and offers us this novel spilling with vitriol and sadness. (Why else would the copy I got be wrapped with two jackets, as if to contain all the acid within?)

Brimming with anger, Roy’s novel is completely scatological as well, liberally using the words forbidden by the moral classes that dominate today’s discourse, as if to dare them. Even the bright yellow Amaltas flower that blooms in Delhi says “fuck you” to the sky over and over again. In case the western reader fails to understand all the Delhi gaalis that liberally italicise the text, the author gives the translation as well, which considerably helps those like this author who use these words on the streets and the parlours of Delhi without really understanding their underlying mysteries.

In 2011, Hazare went on an indefinite fast to push for the passing of the Lokpal bill. Photo: Anil Shakya

In terms of polemic and sarcasm and the big sword that she pierces into the heart of the ruling establishment, nothing has been written in India to match this. Jantar Mantar, Nizamuddin and Old Delhi are her favourite hunting grounds. Roy goes to Jantar Mantar to completely demolish Anna Hazare and Kejriwal (Aggarwal in the novel) for what the author terms a pretend war against corruption. “Like a good prospector the old man had tapped into a rich seam, a reservoir against public anger and much to his own surprise had become a cult figure overnight.” To Anna she credits part of the middle class sense of entitlement and anger against the underclass which sustains many governments in India today. “Doodh maangogey to kheer dengey! Kashmir maangogey to chiir dengey!”

A Booker winner is entitled to take this majestic leap of faith to create a modern-day classic. Too many complications and complexities, the product of such ambition, destroy the flow of the book. Much of the stuff could have been done away with but which editor can suggest this to Roy without being put down?

Roy sees Delhi as very few have, and big novels are set in big cities. She sees the city as an evolving story. As a modern Indian novel in English, (most Indian novels are set in various comfort zones so as not to disturb its target audience) for its scale, its understanding of the larger hidden Indian story, its complete empathy with the underclasses, its utter scorn for the pot bellied ruling classes and their devious take-over schemes, the book is a classic. With this and some earlier novels, we can hope that the Indian English novel is finally liberated from, the concerns of the ruthlessly greedy middle class.

Few novels I have read or read about, have so totally identified with the deprived and the sad. Was she telling the unseen or telling the stories we refuse to see? Either way, Roy has given us a masterpiece to talk about for many years. If not anything, we all need to feel angry for a lot of things.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

You may like

-

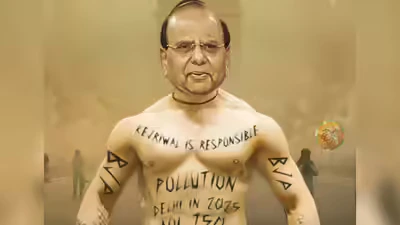

AAP targets Delhi LG with Ghajini dig over pollution row, BJP hits back

-

AAP dominates Punjab zila parishad polls, leads in most panchayat samiti zones

-

Institute for Interdisciplinary Research inaugurated in New Delhi

-

Kejriwal criticizes PM Modi, calls India-US trade talks surrender to Trump

-

Arvind Kejriwal slams Centre after ED raids on Saurabh Bharadwaj, calls It political vendetta

-

Arvind Kejriwal questions Amit Shah over proposed law to sack jailed ministers

Book reviews

Almost 10, Raisina Chronicles reveals the leaps and challenges of Raisina Dialogue, read review

Published

12 months agoon

March 20, 2025

By Subodh Gargya

Raisina Chronicles is a book based on the Raisina Dialogue, a multilateral conference on global politics and economy, which has been held every year in New Delhi since 2016.

The programme is organized by the Ministry of External Affairs and the Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar and ORF President Samir Saran have edited Raisina Chronicles, a book marking the completion of 10 years of the Raisina Dialogue. It explains how the Raisina Dialogue is a medium for countries to discuss challenges facing them led by India.

The Raisina Dialogue’s message highlights India’s growing influence in the world. The book is a bird’s-eye view of geo-political events in the last decade and the views of world leaders on them. The book includes speeches given by world leaders during the Raisina Dialogue.

The first section describes the changes in the global system. This includes the speeches of PM Modi and UN Secretary General António Guterres. The second section explains how countries around the world have come together on some things. The third section dwells on new opportunities for Europe in the Indo-Pacific region. The fourth section discusses security around the world while the fifth explains how Covid-19 has given countries an opportunity to think anew. The sixth section outlines a new perspective on development. In the seventh and final section, it focuses on India’s role and the contribution of the Raisina Dialogue.

The book shares PM Narendra Modi’s view that in today’s time, listening is more important than speaking. Every idea should be heard, thus dialogue is the food of life.

Apart from communication between countries, the editors of the book clarify that its purpose is also to work on differences as the platform respects diversity in ideas. Leaders, business, media, journalists and people from civil society participate in the Raisina Dialogue.

Book reviews

Walking On The Razor’s Edge: The path of the seeker

Published

2 years agoon

July 19, 2024

The Power of Karma Yoga by Gopi Chandra Das (Jaico Books) is an attempt to unravel the mystique of the Bhagavad Gita in the contemporary context. Is Lord Krishna’s counsel to Arjuna still relevant in today’s time and social space ? How can the timeless teachings of Lord Krishna be adopted by people struggling to cope with the stresses and challenges of modern life? Is there a key teaching which can be easily adopted by stress-torn people? These and many more questions are answered by the author in his easy-to-read style.

The basic premise is that the stress is a function of identity; identity with ego or with role-playing. We all play roles in life: in the family, the office and in the social sphere. These roles demand close identification and exact their cost by way of fear, frustration and failures.

The way out is to ease one’s sense of identity with one’s temporal roles. At the metaphysical level, it means keeping oneself in a detached state from one’s ego. This requires sustained spiritual discipline, but automatically yields to mental distancing with mundane roles as well. No wonder the Katha Upanishad compares the spiritual path to a razor’s edge.

Lord Krishna sought to instil this detached perspective in Arjuna by underlining the perishable nature of the body and the transitory nature of the world. However, the key is to strike a balance between total detachment and total attachment. The golden mean is attained by letting go with discrimination. If we detach too much, it will become difficult to perform our duties; if we cling too much, the material will become a millstone. The idea is to be in the world and yet not be of it. As the Persian saint Abu Said said, “To buy and sell and yet never forget God.”

Detachment, however, doesn’t mean irresponsibility. On the contrary, it means working with utter responsibility; with a sense that the job at hand is a moment to glorify the divine. It is not only work for work’s sake; work is taken up as a tool for self-realization. This is more deeply grasped if we acknowledge that the Gita is not only a handbook of divine knowledge or spiritualised action but essentially a guidepost for the man treading the path of enlightenment.

Sri Aurobindo says: “The Gita is not a weapon for dialectical warfare; it is a gate opening on the whole world of spiritual truth and experience, and the view it gives us embraces all the provinces of that supreme region. It maps out, but it does not cut up or build walls or hedges to confine our vision.”

Or as Paramahansa Yoganananda puts it: Gita sheds light on any point of life in which the devotee finds himself in.

Delving yet further, Gopinath explains in the book that letting go is made easy by the practice of apagriha, or being unattached to desires with conscious control on attachment-driven strivings. In the process, one’s motive gets transformed from want-driven to purpose-driven. The aim, at the highest level, being self-realization: the acme of spiritual strivings. For all material strivings ought to be in essence spititual strivings.

When we shift from want-driven to purpose-driven action, the need for personal validation ceases. In our quest for a spiritual-centric action mode, yagna plays an important role. The concept of yagna is transposed from a religious fire-rite to diurnal mundane acts in which personal motives are quenched. As the borderline between the spiritual and the material gets increasingly dissolved, the quest for enlightenment becomes the summum bonum of life.

The direction and blessings of a sadguru is also needed in this eternal quest for soul freedom. In the ultimate sense, the material life and its duties become a stepping stone for a higher life which man embraces to achieve the state of kaivalya. The book lucidly interweaves real-life stories with philosophical concepts, which make for interesting reading.

Book reviews

The Sattvik Kitchen review: Relook at ancient food practices in modern times

If you are the one looking to embrace healthy food habits without compromising on modern delicacies, then this book is a must read!

Published

2 years agoon

February 10, 2024By

The cacophony of bizarre food combinations across the streets of India has almost taken over the concept of healthy food practices. Amid this, yoga guru Dr Hansaji Yogendra’s The Sattvik Kitchen, published by Rupa, is a forthright work that takes you back to ancient food practices and Ayurveda.

As the subtitle reads, The Art and Science of Healthy Living, the book endows a holistic approach to ayurvedic diet along with modern evidence based nutrition. From Basil-Broccoli Soup to Sprouted Green Gram Salad and Strawberry Oats Smoothie to Mixed Dal Parathas, the book not only provides you with the recipes but also stresses on healthy cooking tips together with nutritional benefits.

Besides, Dr Hansaji Yogendra’s book emphasizes on the traditional methods of food preparation and the advantages of using traditional cookwares like iron and copper vessels. The narrative portrays a balanced approach, knitting traditional wisdom with contemporary scientific understanding.

The author, through her book, sheds light on the principles of Ayurveda and highlights the metamorphic potential of adopting ancient food practices. She explains how our body reacts to food in terms of timing, quantity, manner of consumption and seasonal considerations. The book adeptly reintroduces ancient home remedies tailored to address various contemporary health issues.

Dr Yogendra, in her book, decodes the importance of nutritional knowledge to optimize both immediate and long-term health outcomes. It provides deep insights to understanding the intricate relationship between food choices and overall well-being, weaving Ayurveda with practical perception.

The book not only celebrates food philosophy but also offers a practical view into weight loss, well-being, and the profound impact of dietary choices on both physical and emotional aspects of our lives.

If you are the one looking to embrace healthy food habits without compromising on modern delicacies, then this book is a must read! The book is a roadmap to navigate the challenges of the modern day kitchens.

Mamata Banerjee questions PM Modi’s respect for President Murmu using 2024 photograph

PM Modi praises Team India after historic T20 World Cup triumph

India’s T20 World Cup triumph validates Gautam Gambhir’s approach, coach dedicates win to Dravid and Laxman

Mojtaba Khamenei named Iran’s new supreme leader after death of Ali Khamenei