[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text](An extract from The Gift of Anger by Arun Gandhi, internationally renowned activist, speaker and grandson of Mahatma Gandhi)

By Arun Gandhi

We were going to visit Grandfather. To me, he was not the great Mahatma Gandhi whom the world revered but just “Bapuji,” the kindly grandfather my parents talked about often. Coming to visit him in India from our home in South Africa required a long journey. We had just endured a sixteen-hour trip on a crowded train from Mumbai, packed into a third-class compartment that reeked of cigarettes and sweat and the smoke from the steam engine. We were all tired as the train chugged into the Wardha station and it felt good to escape the coal dust and step onto the platform and gulp fresh air.

It was barely nine in the morning, but the early sun was blazing hot. The station was just a platform with a single room for the stationmaster, but my dad found a porter in a long red shirt and loincloth to help us with our bags and lead us to where the horse buggies (called tongas in India) were waiting. Dad lifted Ela, my six-year-old sister, onto the buggy and asked me to get in next to her. He and Mom would walk behind.

“ I’ll walk too,” I said.

“It’s a long distance—probably eight miles,” Dad pointed out.

“That is not a problem for me,” I insisted. I was twelve years old and wanted to appear tough.

It didn’t take long to regret my decision. The sun kept getting hotter, and the road was paved for only about a mile from the station. Before long I was tired and sweat soaked and covered with dust and grime, but I knew that I couldn’t climb into the buggy now. At home the rule was that if you said something, you had to back it up with action. It didn’t matter if my ego was stronger than my legs—I had to keep going.

Finally we approached Bapuji’s ashram, called Sevagram. After all our travels, we had reached a remote spot, in the poorest of the poor heartland of India. I had heard so much about the beauty and love Grandfather brought to the world that I might have expected blossoming flowers and fl owing waterfalls. Instead the place appeared fl at, dry, dusty, and unremarkable, with some mud huts around an open common space. Had I come so far for this barren, unimpressive spot? I thought there might be at least a welcome party to greet us, but nobody seemed to pay any attention to our arrival. “Where is everybody?” I asked my mom.

We went to a simple hut where I took a bath and scrubbed my face. I had met Bapuji once before, when I was fi ve years old, but I didn’t remember the visit, and I was slightly nervous now for our second meeting. My parents had told us to be on good behaviour when greeting Grandfather because he was an important man.

My parents and Ela stayed just a few days at the ashram before heading off to visit my mother’s large family in other parts of India. But I was to live and travel with Bapuji for the next two years, as I grew from a naïve child of twelve to a wiser young man of fourteen. In that time, I learned from him lessons that forever changed the direction of my life.

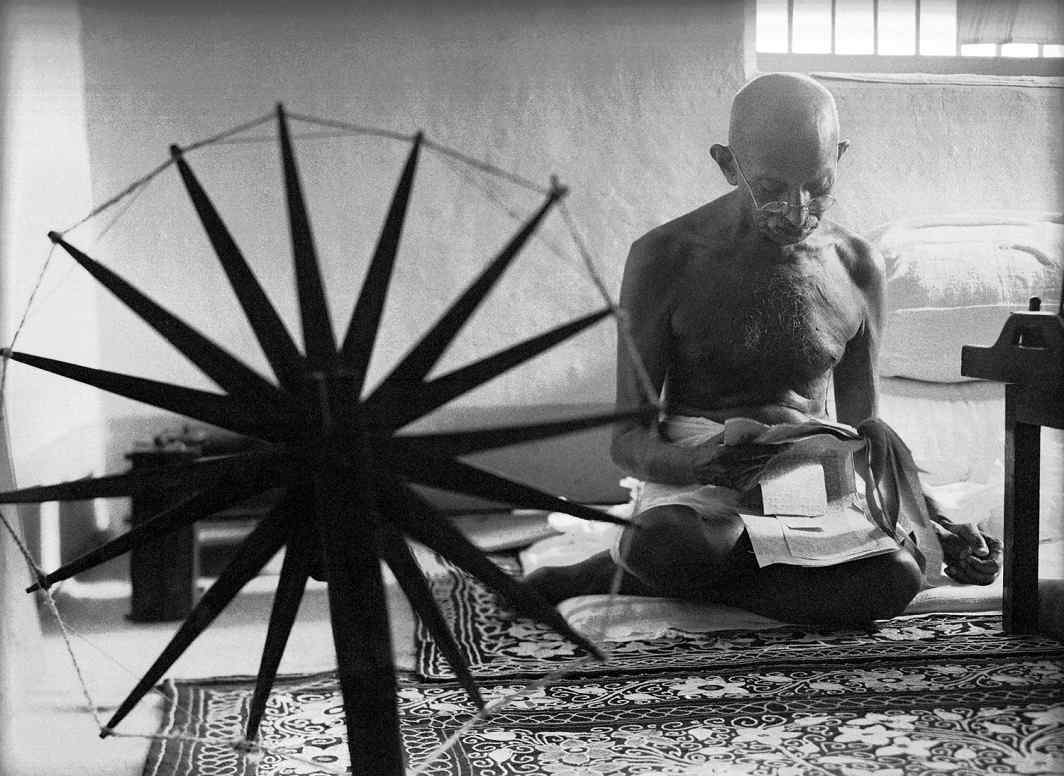

Bapuji often had a spinning wheel at his side, and I like to think of his life as a golden thread of stories and lessons that continue to weave in and out through the generations, making a stronger fabric for all our lives. Many people now know my grandfather only from the movies, or they remember that he started the nonviolence movements that eventually came to the United States and helped bring about civil rights. But I knew speaking reverentially about him, and I imagined that somewhere on the grounds of the ashram was the mansion where Bapuji lived, surrounded by a swarm of attendants.

Instead, I was shocked when we walked to another simple hut and stepped across a mud-floor veranda into a room no more than ten by fourteen feet. There was Bapuji, squatting in a corner of the floor on a thin cotton mattress.

Later I would learn that visiting heads of state squatted on mats next to him to talk and consult with the great Gandhi. But now Bapuji gave us his beautiful, toothless smile and beckoned us forward. Following our parents’ lead, my sister and I went to bow at his feet in traditional Indian obeisance. He would have none of that, quickly pulling us to him to give us affectionate hugs. He kissed us on both cheeks, and Ela squealed with surprise and delight.

“How was your journey?” Bapuji asked.

I was so overawed that I stuttered, “Bapuji, I walked all the way from the station.”

He laughed and I saw a twinkle in his eye. “Is that so? I am so proud of you,” he said, and planted more kisses on my cheeks.

I could immediately feel his unconditional love, and that to me was all the blessing I needed. But there were many more blessings to come.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Latest world news21 hours ago

Latest world news21 hours ago

India News20 hours ago

India News20 hours ago

Latest world news20 hours ago

Latest world news20 hours ago

Latest world news21 hours ago

Latest world news21 hours ago

India News20 hours ago

India News20 hours ago