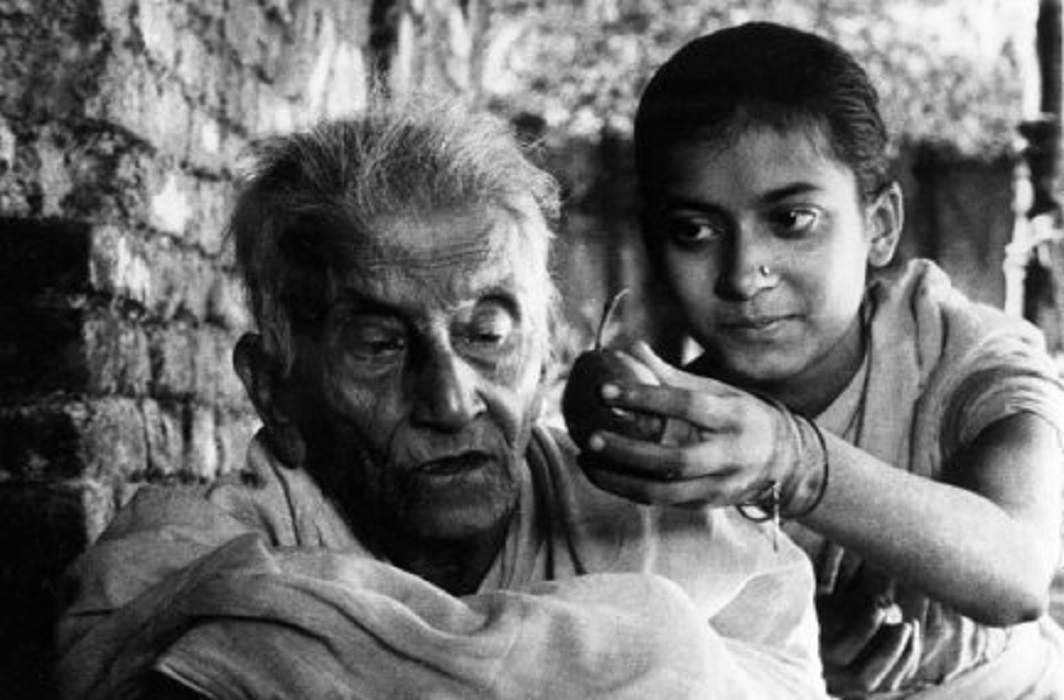

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]It is her portrayal of Indir Thakrun that makes Ray’s Pather Panchali unforgettable

By Khalid Mohamed

As many as 62 years ago, Satyajit Ray’s PatherPanchali (SongoftheRoad) had competed for the Palme D’Or at the Cannes film festival where it won the Best Human Document Award.

At India’s 3rd National Film Awards in 1955, it was named Best Feature Film and Best Bengali Feature Film.

Still a bestseller on DVD, it is saluted to this day and age by the global critics and connoisseurs of cinema as the best – if not the most well-known film– to have emerged from India.

The classic is enshrined in the memory, especially for a singular performance which touched the viewer emotionally rather than revealing any excess which would could have lapsed into rank sentimentality.

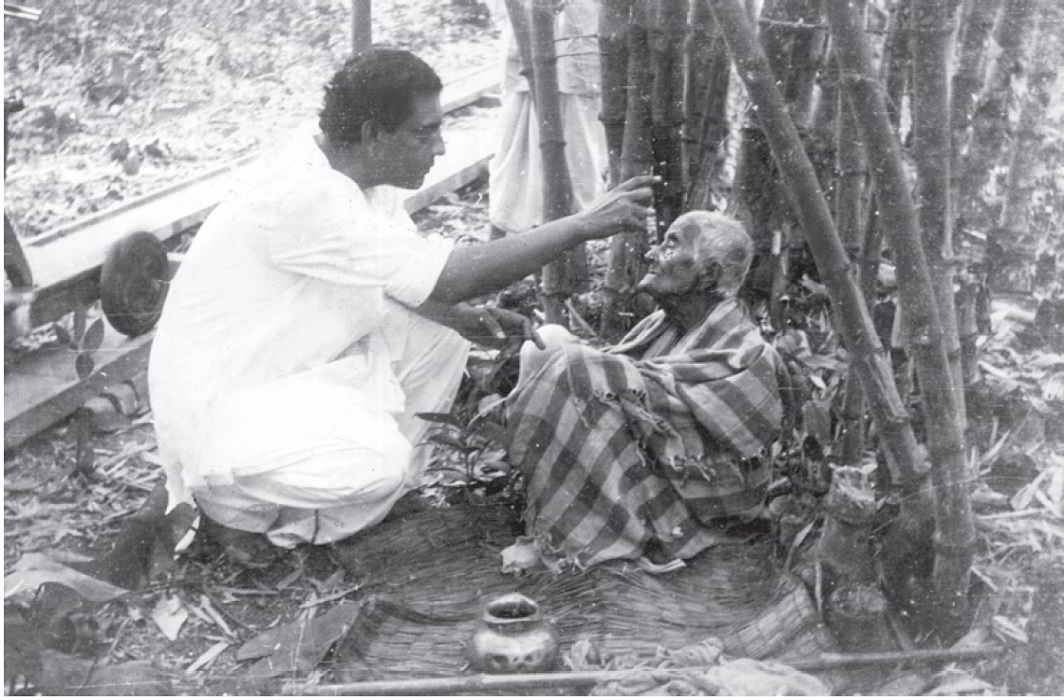

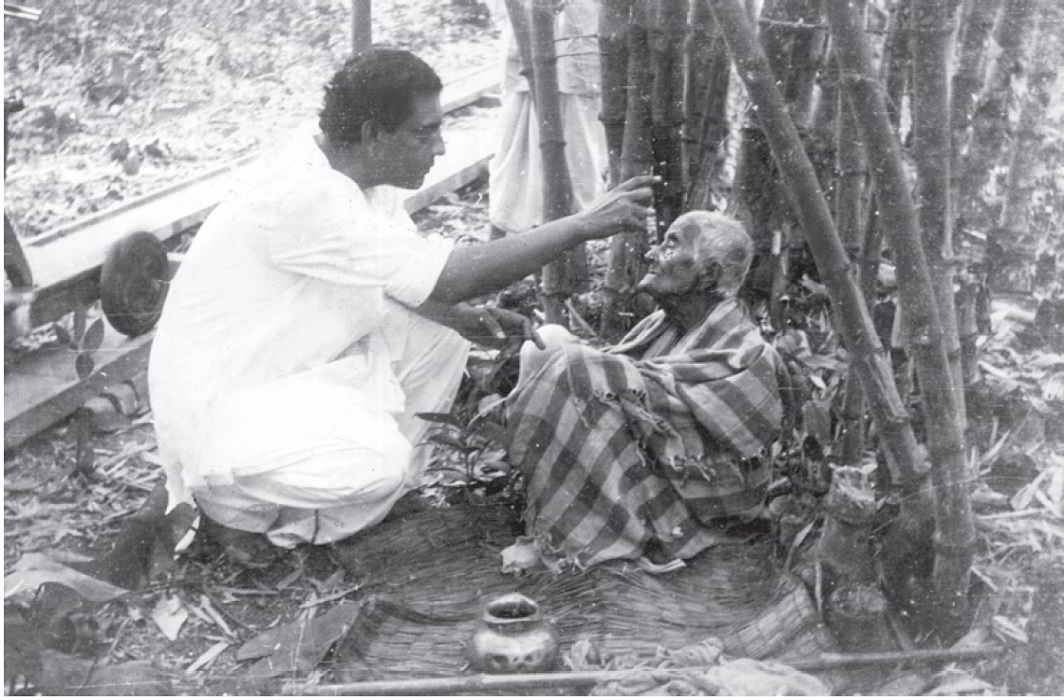

The performance was extracted from Chunibala Devi, who at the age of 80, incarnated the curmudgeonly and yet heartbreakingly lovable Indir Thakrun for Ray’s first feature film, adapted from a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandhophadyaya. Lore has it that circa, Ray couldn’t finalise an actress for the role after meeting several octogenarians who were either too senile or given to cosmetics and artificial mannerisms.

Accompanied by his production manager, the filmmaker knocked on the doors of a brothel in north Calcutta,where they were welcomed by its madame, who asked business-like, “Would you like to see the girls?” Not quite. Ray asked the madame if she would act in his film.

Although he had no credentials and could promise her a meagre fee of Rs 20 a workday, Chunibala Devi was thrilled. From the world’s oldest profession, she would be returning to the one she had excelled in during the best years of her life.

A popular stage actress, Chunibala Devi had also acted in a clutch of films of which the two most successful ones – Bigraha (1930) and Rikta (1939). Her astoundingly naturalistic performance of the old crone in PatherPanchalifetched her top honours at the Manila international film festival. Perhaps, if she had been awarded by the jury at the Cannes, Berlin or Venice festivals, it would have been celebrated at home more robustly. In any case, that wouldn’t have mattered. She passed away after a bout of influenza, before PatherPanchali was released in her homeland.

According to Andrew Robinson’s seminal book SatyajitRay:TheInnerEye (1989), the old lady had the qualities of what makes a fine actress: discursive but not obstinate, eventually surrendering to the director’s vision. She begged to differ vehemently on the picturisation of her death scene which was set at a village shrine, in the book.

Ray had altered the location to a neutral spot, focusing on the silence and the inevitability of her death. Indir Thakrun is shown squatting, and on being prodded, her head hits the ground. It wasn’t the possibility of getting injured but the departure from the original text which bothered her. Surrendering to Ray, she followed his instructions, elating the auteur as well as the crew once the scene was performed to perfection at first take.

The next scene, showing her body being carried on a bamboo bier for the funeral rites, down a desolate village path, is unforgettable for its elegiac impact. It was to be picturised at 5 a.m. at Boral, a village at a manageable drive away from Calcutta. Chunibala arrived in a taxi at the dot of time, allowed her frail body to be tied up with ropes, and the shot was on after a rehearsal.

Once the shot was over, she didn’t stir. The unit was alarmed, “Could she be really dead?” On being prodded she smiled toothlessly, and huffed, “Is the shot over? Why didn’t anyone tell me? I’m still here lying dead.”

One can only presume that after that death scene, the actress returned to her home in the red-light neighbourhood. What drove her there after acting on stage and screen, however, is a hard-luck story which affirms that female artistes have always been relatively poorly paid and aren’t insured, to this day and age, against penury.

So many celebrated actresses from the 1940s and ‘50s have faded out into sunset boulevards in the bright bustling Bollywood, too, their neglect buried with them. In fact, old-timers recount how a B-grade comedienne and a heroine of the ‘60s, was compelled to survive by operating ‘houses of ill-fame’. Ill fame! How chauvinistic does that sound? No one wants to leave the fame game unless she has no option. No one leaves unless given the marching orders.

Quite gloriously, Chunibala Devi seized the option to return, and firmly proved that age cannot prevent the recreation of magic in front of the eye of the camera. That required stamina. Again lore has it that she would keep herself together by taking her daily pinch of opium. The one day she didn’t, she was distraught, she couldn’t speak.

Indeed, when she’s squatting, bends over and dies in PatherPanchali, that was her last big hurrah. TheSongoftheRoad, couldn’t ever have been sung without her.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

India News19 hours ago

India News19 hours ago

India News18 hours ago

India News18 hours ago

India News9 hours ago

India News9 hours ago

Cricket news8 hours ago

Cricket news8 hours ago

India News8 hours ago

India News8 hours ago