[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The acclaimed actor, sports journalist, Padma Shri awardee and Urdu lover was recently diagnosed with skin cancer. He was 67

– By Puneet Nicholas Yadav

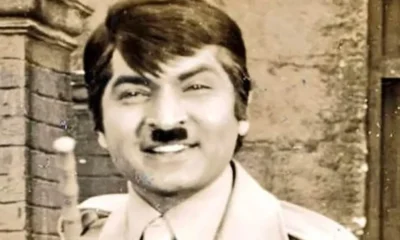

An acclaimed actor, sports journalist, Padma Shri awardee and Urdu lover, Tom Alter, is no more. The blue-eyed ‘saheb’ of Indian cinema, who portrayed a wide range of characters through his nearly four decade long acting career that saw him feature in over 300 films, was recently diagnosed with terminal stage of skin cancer and admitted to Mumbai’s Saifee Hospital. He passed away late on Friday night, surrounded with his family members. He was 67.

Born Thomas Beach Alter in Mussourie in 1950, Tom was an American through his family lineage. His grandparents were American missionaries who traveled from Ohio to preach, convert and teach in the part of Punjab that is now in Pakistan. His father, also a missionary, was born in Sialkot (now in Pakistan) and later settled in the Himalayan hill station of Mussourie. Tom went to the famous Woodstock School in Landour with other Americans, children of missionary parents, diplomats, business executives and other ‘settlers’ and later for a brief year-long stint to the prestigious Yale University in New Haven, USA.

But if you ever met the man, you could only risk calling him an American or non-Indian at your own peril. Tom was as Indian as an Indian can be and immensely proud of it. With his impeccable Hindi and flair for Urdu, Tom was quite the anti-thesis of that image of him that most Indian moviegoers are familiar with – that of the ‘gora’ villain, a foreign diplomat or British colonial – roles which typecasted him in Bollywood and for a period won him the moniker of Indian cinema’s ‘blue-eyed sahib’. But then those were roles.

Fiercely proud of his Indian identity, Tom would often speak – in what could turn into a gripping monologue unless he was interrupted – about the ‘idea of India’. The current political and social churning in the country wherein gau rakshaks, lynch-mobs, abusive right-wing trolls and political leaders who promptly advise anyone with views divergent to theirs to ‘go to Pakistan’ was something that affected Tom deeply and he worried about what we were transforming into as a nation. The concept of a Religious State is something Tom never missed to vociferously attack.

In an interview that the actor had given to this writer sometime in 2010, he had minced no words while comparing a Religious State with “the making of a pornographic film”.

In that interview – the substance of which is more relevant today than it perhaps ever was – Tom has said: “I have always held that without India and everything that it stands for the world will be destroyed. If we destroy the secular, democratic and free country that India is and become like other Religious States, the world would come to an end in not more than 25 years.”

“It’s too easy to run a Religious State where there is no freedom of expression or freedom to practice what religion you want to or the freedom to wear what you like. It’s as easy as making pornography. But then Religious States will disappear without a trace, no one will remember them for anything good, just as no one remembers names of any directors of pornography,” Tom had said.

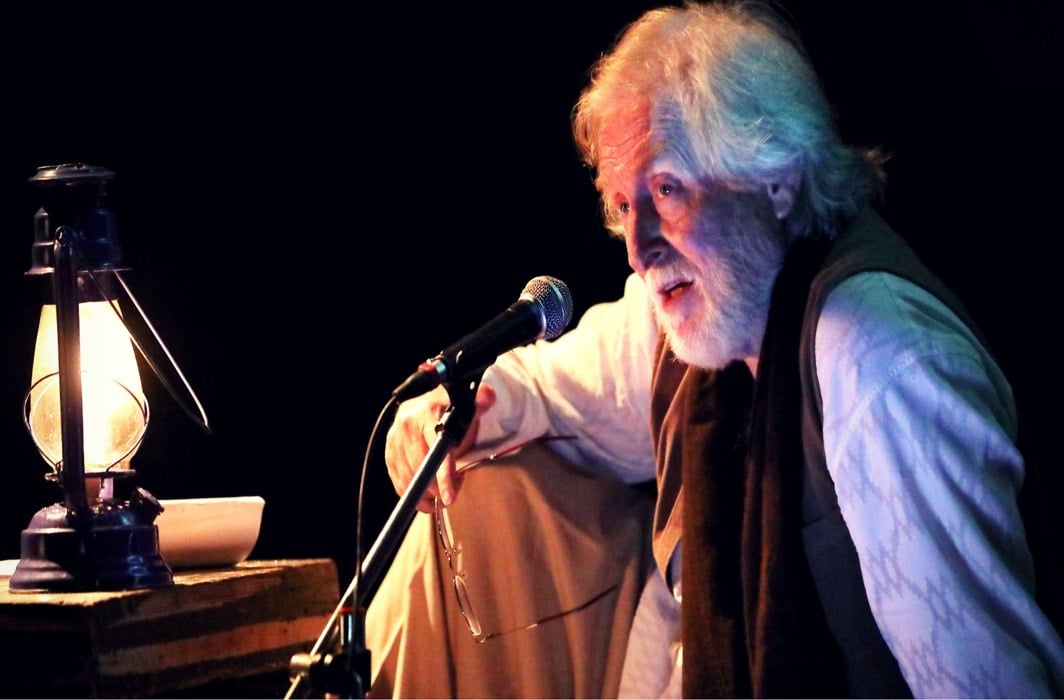

The actor, who essayed the role of freedom fighter and India’s first education minister Maulana Azad on stage in the highly acclaimed play ‘Maulana’, believed that India’s real challenge today is to preserve its secular and democratic set up, traits that he believed had taken a beating over the years.

His pride in India aside, Tom was always just as passionate about the one thing that got him international acclaim and recognition – acting – a craft which, ironically, wasn’t his first love when he started off in life. He was more interested in sports, cricket in particular, and pursued a simultaneous career as a sports writer in the 1980s and 1990s even when big roles in films began coming his way. He was the first person to interview Sachin Tendulkar for a television channel in the 1980s, much before the cricketer earned his iconic status. His love for cricket stayed with him till the end. When this writer met him in Bhopal a couple of year ago – where he had come to perform Maluana to a packed audience at the Ravindra Bhavan – Tom had admitted that he missed writing on sports as often as he would like.

Tom had started off as a teacher in a hamlet called Jagadri in Haryana at the age of 19 and in those days rarely watched Hindi films. But then that same year, almost like the script of a good Bollywood film, his life took a sudden turn when he saw the then reigning superstar of India, Rajesh Khanna, romancing the stunning Sharmila Tagore in the cult film Aradhana that had released in September 1969.

Tom would often remark – “I saw Aradhna over and over again and was in love with Rajesh Khanna. I wanted to become Rajesh Khanna. I packed up my stuff and decided to quit my teaching role in Jagadri and move to Mumbai”.

In 1972, Tom became one of only three aspirants – the other two being actor Benjamin Gilani and Phunsok Ladakhi – to be selected from a batch of over 800 candidates from across north and central India to get selected for the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Pune. Tom’s talent in acting was evident during his stint at FTII from where he passed out in 1974, winning a gold medal in his acting diploma course. At the FTII, he struck a close bond with Naseeruddin Shah. Tom, Naseeruddin Shah and Benjamin Gilani would go on to form the theatre troupe- Motley – in 1979.

After the initial struggle to find his feet in the fiercely competitive world of Bollywood where he had no godfather, Tom got a break in Ramanand Sagar’s 1976 production, Charas, in which he played actor Dharmendra’s ‘firang’ boss. Dharmendra was already a huge deal among Indian cinemagoers then but Tom managed to make a mark and was noticed by other directors and producers who began offering him roles – though largely of the same sort – that of a ‘gora’ character. This stereotype of playing the ‘blue-eyed saheb’ would break only occasionally, particularly in films like Raj Kapoor’s Ram Teri Ganga Maili or Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s Parinda in which he played pivotal roles and as an Indian character.

Through his career, Tom worked with leading actors, producers and directors – the likes of Chetan Anand, Dev Anand, V Shantaram, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Manmohan Desai, Shyam Benegal and Subhash Ghai, Mahesh Bhatt, Ketan Mehta, Priyadarshan and even Satyajit Ray. Offers of working in foreign productions too came along and Tom did pick up roles in Richard Attenborough’s Oscar-winning film Gandhi and the Peter O’Toole starrer One Night with the King.

While his acting resume expanded with each passing year, Tom also ventured into theatre giving audiences stellar, mind-blowing performances in plays like Ghalib ke Khat, Maulana (both in chaste Urdu), Lal Qile ka Aakhri Mushaira, Trisanga, Teesveen Shatabdi, Copenhagen and the City of Djinns.

But unlike several Indian actors – like his dear friend Naseeruddin Shah – who are associated with both theatre and cinema, Tom never took a dim view of the Indian film industry. “Whatever I am today is because of the roles – even the bad ones – that I got in Indian movies. I can never, ever disown the Indian film industry or criticise it”, Tom told this writer once.

When asked if he regretted not having become a ‘star’ in Indian cinema despite his indisputable talent, Tom had said: “You need that flair to present yourself, market your work. Theatre actors don’t do that.” When this writer asked him if he lacked the ‘flair’, Tom had candidly replied: “I think I did have the flair but I made some wrong decisions in the beginning of my career. Also there were some films I did which unfortunately never released. Had they released perhaps they could have pushed me in a different league. But I have no regrets.”

A question that Tom would hate being asked was “how are you so good with Urdu”. For a layman who wasn’t familiar with Tom’s body or work or his upbringing, this might seem an obvious question given the ‘colour’ of Tom’s skin. But Tom would almost lose his famous temper (if he was in one of those moods) or have some witty repartee for such a question.

“I learnt Urdu as a child. Everyone spoke in Urdu where we lived,” he had once told this writer. Tom’s father was well versed with Urdu and even read the Bible in the language – something that Tom followed too. Tom would pick up Urdu books, dictionaries (though one felt that he never really needed them because he understood the language better than even some Urdu scholars) and poetry whenever he got a chance, and would get extremely agitated by anyone who ignorantly associated the language with Pakistan.

“Gandhiji gave the language a beautiful name- Hindustani. He learnt the language and its script. He even wanted all members of the Congress to learn both Devanagari and Urdu scripts… The Pakistanis today say Urdu is their national language. I tell them are you mad! How can Urdu be the language of the Pakistanis? The language was born in India, in Delhi,” this writer remembers Tom telling an interviewer once.

Tom had some quirks too and the most irritating one for the people who knew him was his extremely stubborn dislike for mobile phones – “I hate the damn thing” – he would often say when asked why he didn’t have a cellphone or told that it was difficult to get in touch with him. He felt that mobile phones had connected people from far-flung regions but had also “taken away emotions, inter-personal relations and the ‘tameez’ of a conversation”.

Tom’s calming presence, his vibrant performances, his idealism and his quirks will be missed by anyone who knew him. Rest in peace, Tom Alter, the Indian sahib.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

India News18 hours ago

India News18 hours ago

India News17 hours ago

India News17 hours ago

India News8 hours ago

India News8 hours ago

Cricket news8 hours ago

Cricket news8 hours ago

India News7 hours ago

India News7 hours ago