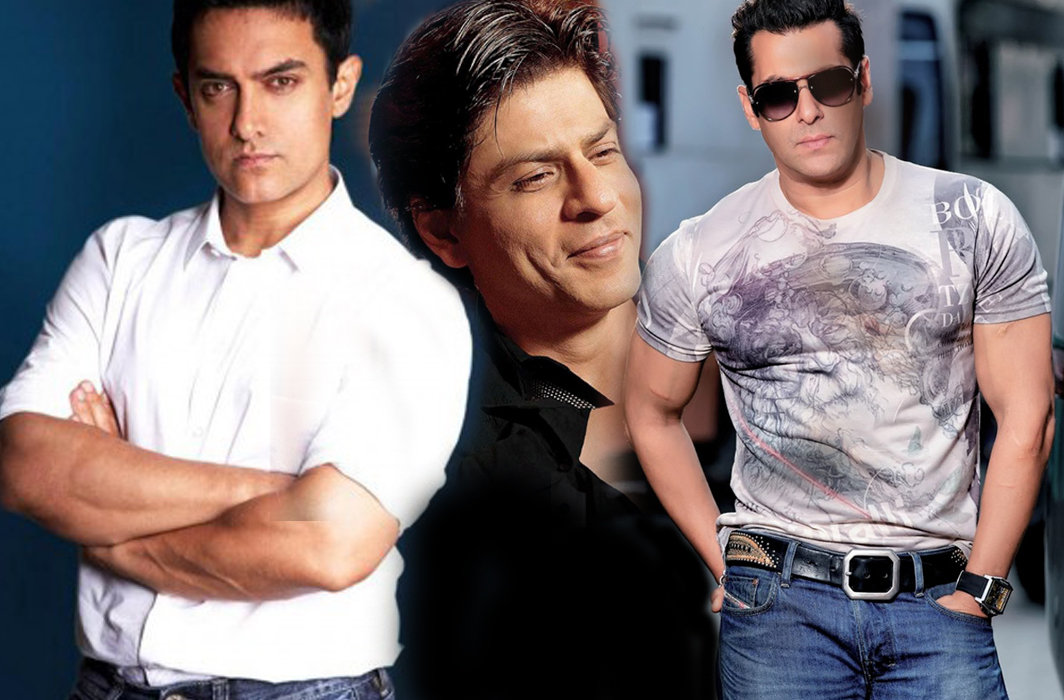

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The three Khans—Aamir, Shah Rukh and Salman—jive on. A new hero, who can appropriate the crown, has been awaited for long. In vain.

By Khalid Mohamed[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

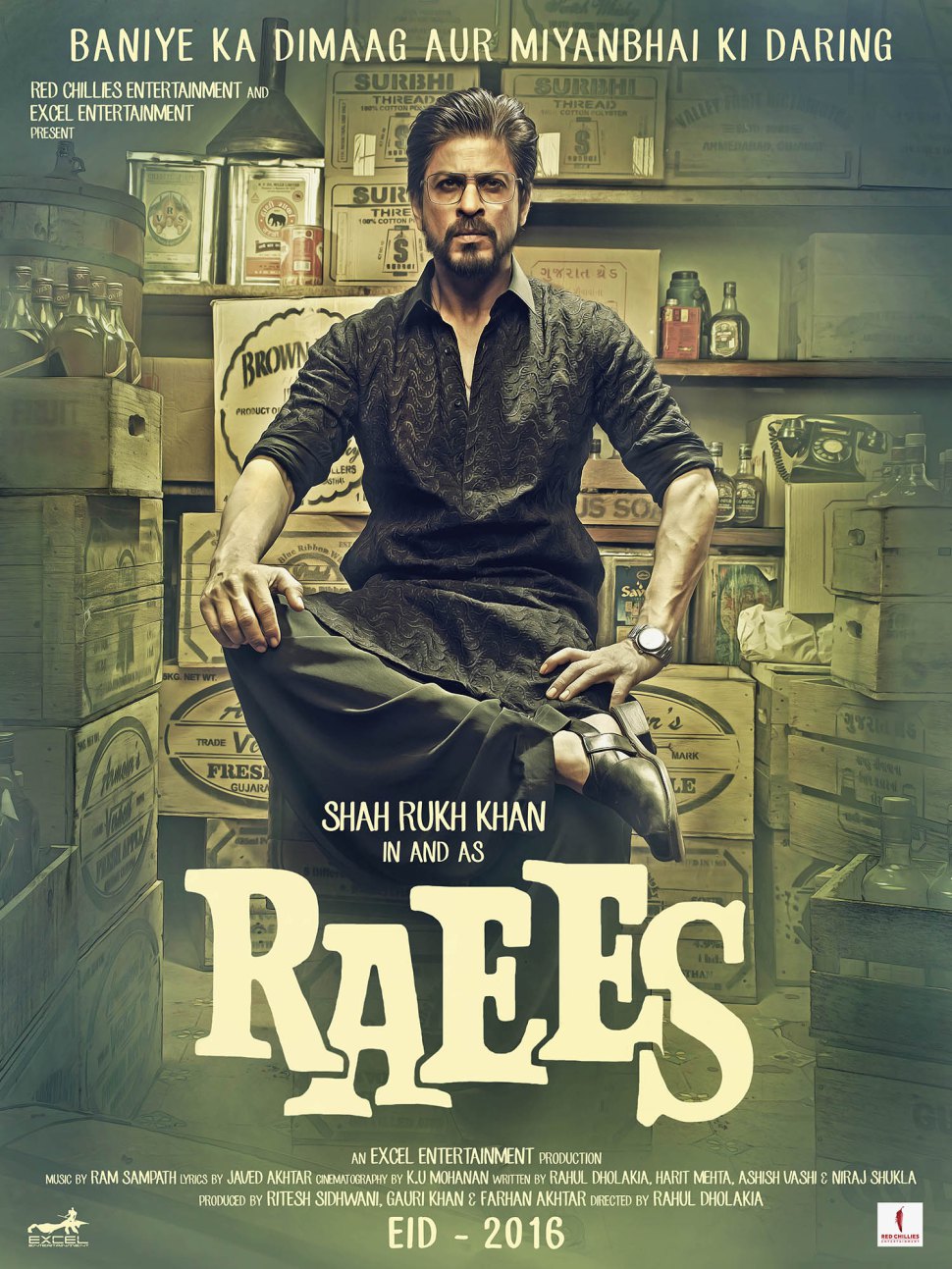

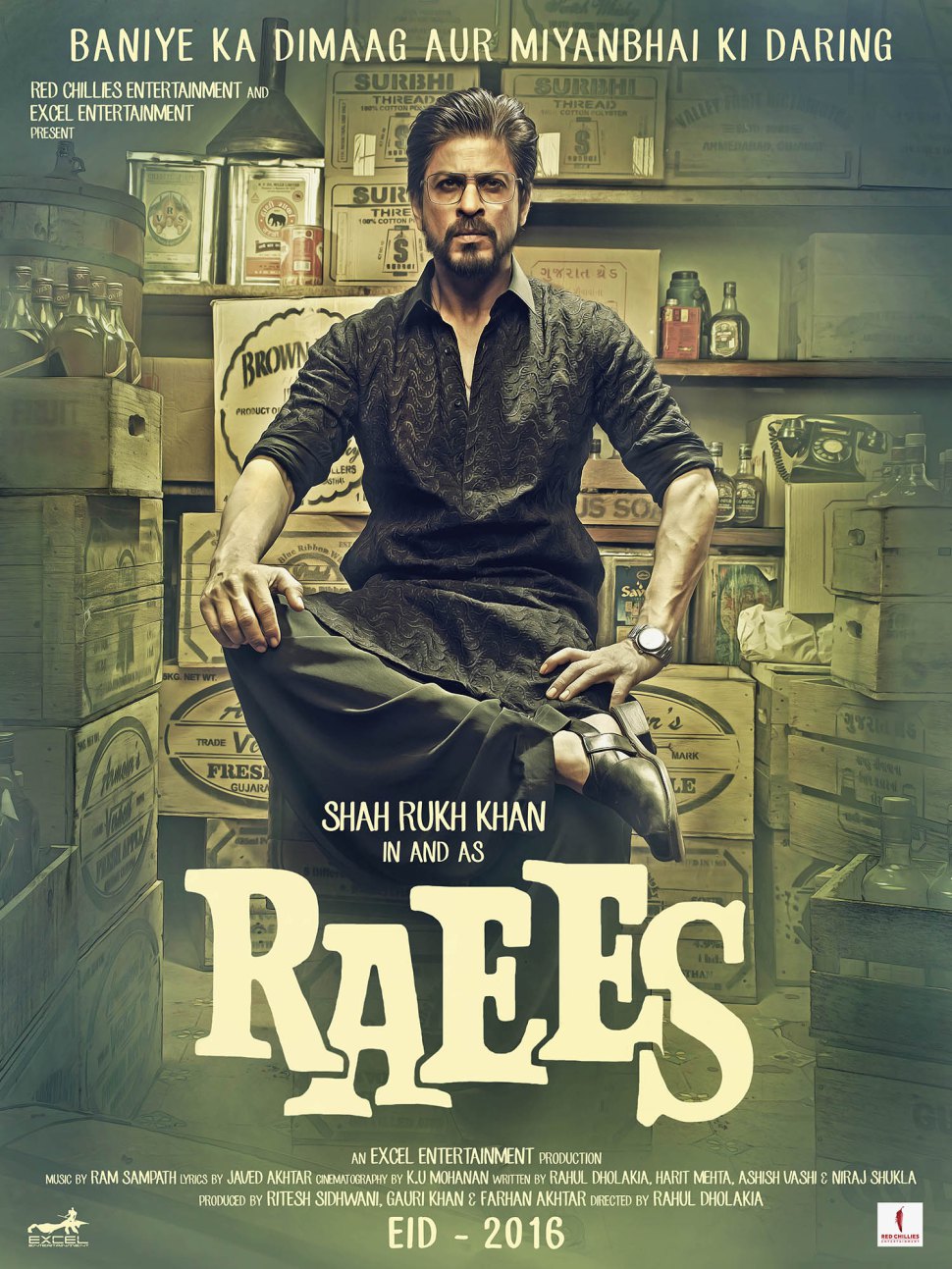

Aamir Khan has just toted the biggest cash-earner of all-time with Dangal. The vigil for Shah Rukh Khan’s Raees has been akin to Waiting for Godot. Salman Khan’s Tubelight and Tiger Zinda Hai—you can bet your last rupee—is already driving his swelling fan following into a state of lather.

Give or take a couple of years, the Khans have formed the presiding trinity for over three decades now, each one of them entering the showbiz maidan towards the end of the 1980s. Aamir kicked off with an enormously successful love story, Salman fretted around the same time in a Rekha-dominated domestic shampoo. Meanwhile, Shah Rukh was making whoopee on the rapidly-developing domain of television.

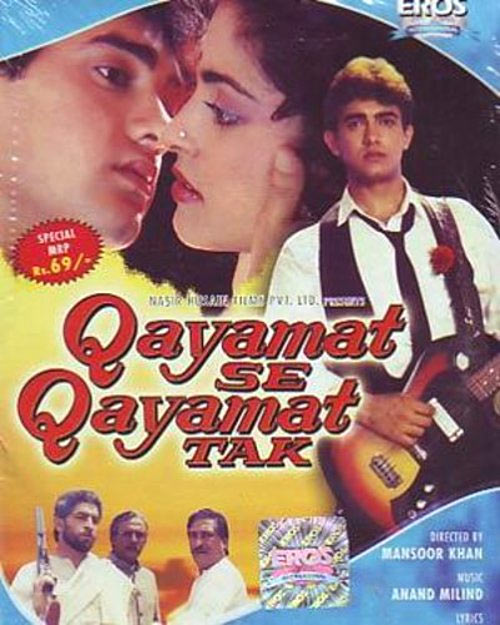

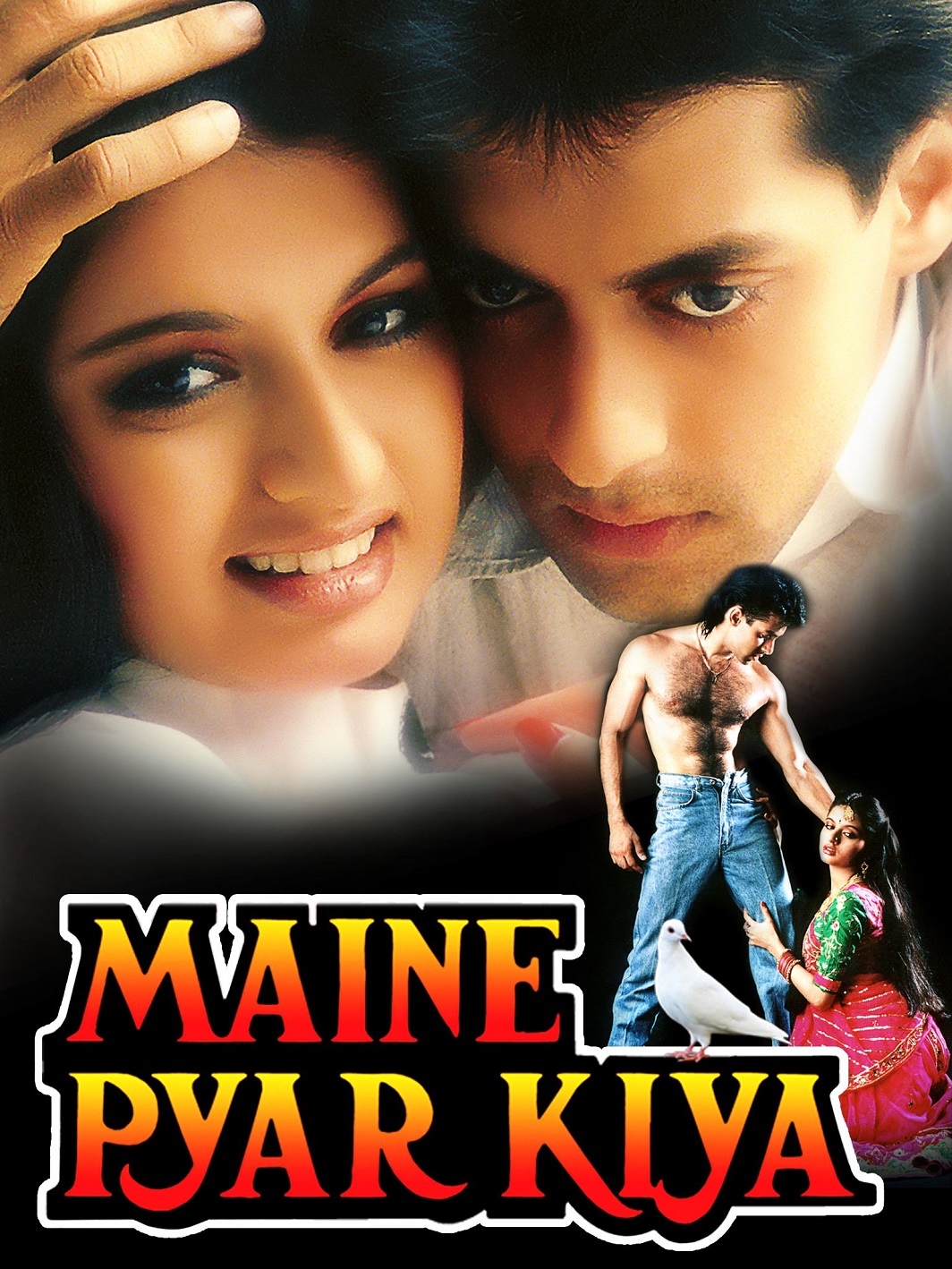

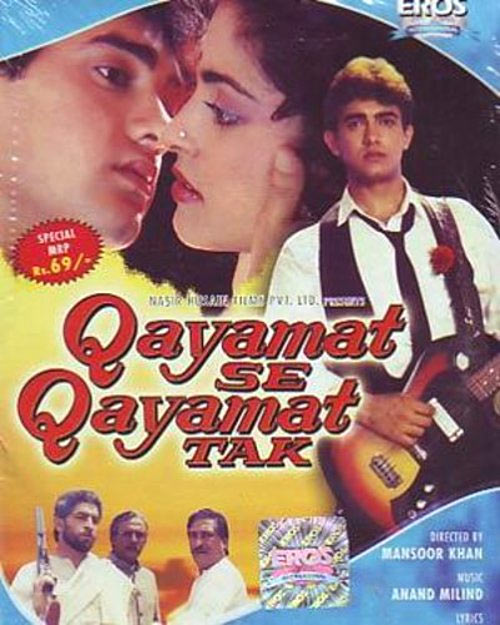

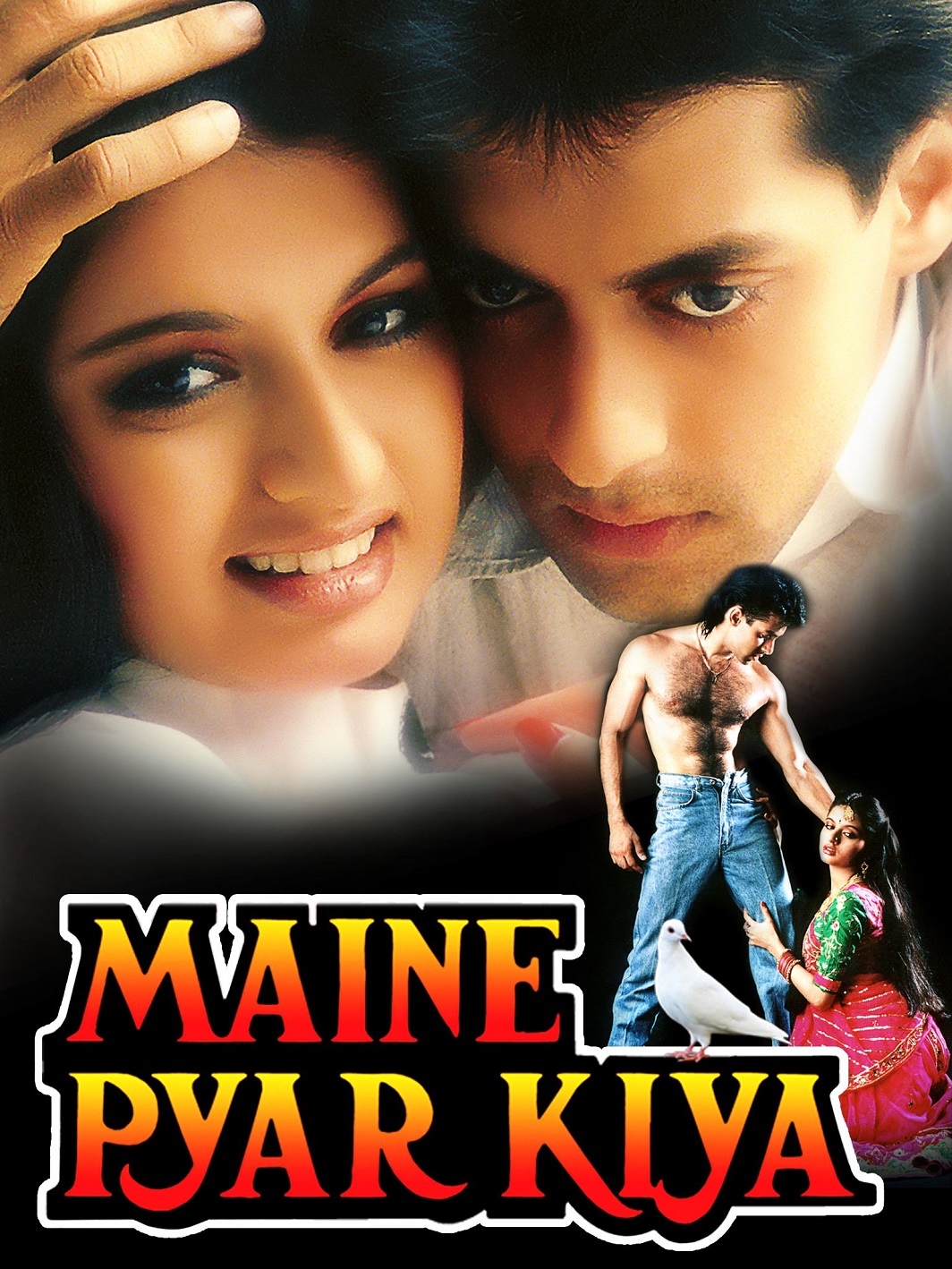

Coincidentally, all three of them had to linger on the margins before striking popularity platinum. For starters, Aamir Khan the dreamy Romeo of Qayamat se Qayamat Tak (1988), Salman Khan the besotted romantic of Maine Pyaar Kiya (1989) and Shah Rukh Khan the bike-riding lover boy of Deewana (1992) had flitted around like moths to the showbiz flame.

Coincidentally, all three of them had to linger on the margins before striking popularity platinum. For starters, Aamir Khan the dreamy Romeo of Qayamat se Qayamat Tak (1988), Salman Khan the besotted romantic of Maine Pyaar Kiya (1989) and Shah Rukh Khan the bike-riding lover boy of Deewana (1992) had flitted around like moths to the showbiz flame.

Give or take a couple of years, the Khans have formed the presiding trinity for over three decades now, each one of them entering the showbiz maidan towards the end of the 1980s.

Aamir Khan assisted his uncle director Nasir Hussain and subsequently acted in the unconventional, quasi-experimental Raakh as well as Holi. Salman Khan modelled for ads, assisted director Shashilal Nair (not too happily, it seems) and was a mere side-plate in Biwi Ho To Aisi.

As for Shah Rukh Khan, he was the small screen Fauji besides showing up in Mani Kaul’s labyrinthine adaptation of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. Formally, the beginnings of the Khans in Film Town could be described as a ‘struggle’, though not in the traditional Amitabh Bachchanesque mode of, “I had to sleep on a Marine Drive bench and have channas for dinner.”

Aamir and Salman originated from film families, Shah Rukh Khan was the New Delhi outsider who made up for his lack of immediate connections with the attention he attracted on Doordarshan. Apart from that, there’s another common factor between the three Khans—none of them is tall.

Aamir and Salman originated from film families, Shah Rukh Khan was the New Delhi outsider who made up for his lack of immediate connections with the attention he attracted on Doordarshan. Apart from that, there’s another common factor between the three Khans—none of them is tall.

Come to think of it, each Khan is a rebuttal of the six-foot-plus tall Angry Young Man persona of Bachchan which had ruled over the public mind before the three young romantics asserted that it’s love—and not rage— which makes the world go round. They courted their petite heroines obsessively, lip-synced to melody-friendly songs, wore costumes which suggested as if they were on casual leave. And most vitally, they were in their 20s when they connected to the nation’s ishq-vishq-pyaar-vaar-deprived audience.

Now they are all 51 years old. Born in 1965, Aamir Khan is the eldest by a few months, having brought in his birthday on March 14. Shah Rukh turned 51 on November 2, and Salman on December 27. Currently, all of them are playing characters of indeterminate age, oftentimes affirming the traditional Bollywood dictum that even at middle-age heroes can discover the initial flush of love.

Salman went goggle-eyed on sighting Sonakshi Sinha in Dabangg, Aamir Khan went ape over Kareena Kapoor in 3 Idiots, ditto Shah Rukh Khan, as the mousy clerk, over Anushka Sharma in Rab ne Bana di Jodi and then again, with the addition of Katrina Kaif, in Jab Tak Hai Jaan.

Obviously heroes, 51-year-old lover boys, are still acceptable in the public mind. In fact, of the trio, Aamir Khan appears to have that Peter Pan quality; he can be overwhelmingly credible even in the roles of a fresh MBA graduate in Dil Chahta Hai or the college smarty in 3 Idiots. By contrast, when he buffs up his body to portray a mean vendetta machine in Ghajini, he may look the part but the viewer does have to suspend his sense of disbelief. Physically-explosive heroism is not his best suit, never mind the huge box-office receipts of the gore-spilling take on Hollywood’s temporary memory loss cult flick Memento.

Each Khan is a rebuttal of the six-foot-plus tall Angry Young Man persona of Bachchan which had ruled over the public mind before the three young romantics asserted that it’s love—and not rage— which makes the world go round

Aamir Khan’s primary strength is his boyishness—allied with the compulsion to do the right thing (read perfectionism, as written in his one-man dictionary). Bulking out a la Robert de Niro in Raging Bull for Dangal is the trick to look real. There’s physical rigour, a political correctness instead of madness in his method.

As an actor, he’s self-directed and not the director’s delight at all. Motivation, why-am-I-doing-this-and-why-am-I-doing-it-like-this?, and a self-consciousness about his image, are elements which may make for a fine actor, but not a great one. Which is why, although he has followed the principle of selecting handpicked films, he cannot achieve the stature of the superb Dilip Kumar.

Among the Khans, he has the lowest score of approximately 45 films. It goes without saying that he is an intelligent actor. Still, you cannot help hoping he would let himself go, just open up without a second thought before the camera. On the upside, his fastidiousness can be interpreted as a sense of responsibility to the audience.

Currently, all of them are playing characters of indeterminate age, oftentimes affirming the traditional Bollywood dictum that even at middle-age heroes can discover the initial flush of love.

If the unchecked violence of Ghajini and the superficial terrorism dialectics of Fanaa were questionable, laurel leaves are called for his impressive performances in Lagaan, Sarfarosh, Rang de Basanti and Dangal which stirred the spirit of nationalism. Plus Taare Zameen Par, sought to remove the bias against dyslexic children. In addition, as a film producer, Peepli Live and Dhobi Ghat have taken the risk of backing away from the formula rules and regulations.

The Aamir Khan who is loved is the Aamir Khan of the entertainers QSQT, Dil Hai Ke Maanta Nahin, Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar, Hum Hain Rahi Pyaar Ke, Andaz Apna Apna, Rangeela and Ghulam. Like all actors, he has had his bloomers too, like Tum Mere Ho (a snake madari adventure!), Daulat ki Jung, Baazi, Aatank hi Aatank and Mela to cite a random few. Today, he’s a brand name equated with superior quality cinema. If there’s a task before him now, it is to push the proverbial envelope further, and become more instinctive than studied before the eye of the camera.

Once, it used to rain surprises in Shah Rukh Khan’s backyard. His uncontrollable energy, unconventional body language and stuttering dialogue have given him a distinctive appeal through a mixed bag of over 60 films. If Aamir Khan’s voice, dialogue delivery and diction were seductively low-key, SRK’s were disturbing. And if AK’s sunshine smile was a mannerism that his fans demanded consistently, SRK’s toss of shampoo-silk hair, a raise of those diabolical Jack Nicholson-like eyebrows and a pout of his lips became his identifying characteristics. More than any other actor of his generation, he relished risks, caring a damn about the good-guy image by investing a psychotic edge to Baazigar, Darr and Anjaam, and who knows, in the upcoming Raees.

Once, it used to rain surprises in Shah Rukh Khan’s backyard. His uncontrollable energy, unconventional body language and stuttering dialogue have given him a distinctive appeal through a mixed bag of over 60 films. If Aamir Khan’s voice, dialogue delivery and diction were seductively low-key, SRK’s were disturbing. And if AK’s sunshine smile was a mannerism that his fans demanded consistently, SRK’s toss of shampoo-silk hair, a raise of those diabolical Jack Nicholson-like eyebrows and a pout of his lips became his identifying characteristics. More than any other actor of his generation, he relished risks, caring a damn about the good-guy image by investing a psychotic edge to Baazigar, Darr and Anjaam, and who knows, in the upcoming Raees.

Heartbreaking sweet on the one hand and intolerably bitter on the other, SRK could be schizoid, two personae-for-the-price-of-one ticket. Striking menace to begin with, he became the nice fella, the cool-kid-next-door with a concatenation of terrific performances in Kabhi Haan Kabhi Na, Yes Boss, Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, and of course, the pitamah of all romances Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge. The nasty stalker had been tamed, he actually wanted to be loved by everyone from his potential in-laws to his barber Billu.

Heartbreaking sweet on the one hand and intolerably bitter on the other, SRK could be schizoid, two personae-for-the-price-of-one ticket. Striking menace to begin with, he became the nice fella, the cool-kid-next-door with a concatenation of terrific performances in Kabhi Haan Kabhi Na, Yes Boss, Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, and of course, the pitamah of all romances Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge. The nasty stalker had been tamed, he actually wanted to be loved by everyone from his potential in-laws to his barber Billu.

SRK attained superstardom, sprinting ahead of the two other Khans for a while. Occasionally, there could be an edgy Dil Se or Josh but for the most part, he became stereotyped as the lovey dovey dude Rahul in Yash Chopra and Karan Johar candy box movies.

If Aamir Khan’s voice, dialogue delivery and diction were seductively low-key, SRK’s were disturbing. And if AK’s sunshine smile was a mannerism that his fans demanded consistently, SRK’s toss of shampoo-silk hair, a raise of those diabolical Jack Nicholson-like eyebrows and a pout of his lips became his identifying characteristics.

Delicious but the star-actor’s career appeared to be veering towards the diabetic. Subsequently, he took on the Devdas role incarnated memorably by Dilip Kumar earlier, and Don walloped out by Amitabh Bachchan in his heyday. Both Devdas and Don saw SRK in form but for sure the best were yet to come…and auspiciously they did: Swades and Chak De! India showcasing SRK without a tick of his patented mannerisms. This gambit of a dual role—upright man versus psychotic man— didn’t quite impress in Fan though.

An intuitive actor, SRK’s strengths are his spontaneity and whooshing energy. Also, he uses his eyes expressively. His weaknesses are to over-illustrate his character (a pout to indicate displeasure, a fling of his arms to underscore rapture, and an unpunctuated ha-ha-ha to denote amusement). Another failing: he cannot determine what is a purposeful film and what is not. After Paheli, he appears more to be averse to medium-budget cinema, and doesn’t speak too fondly of Mani Kaul’s Idiot either.

That’s where Aamir Khan is a cut above SRK today. Aamir can distinguish between cinema of substance and cinema of fluff. Also, SRK’s overexposure through ad endorsements (even plugging furniture upholstery for heaven’s sake) has been downers. With only the special effects-crammed Ra-One and Don 2, the actor didn’t play his cards right at all. Perhaps when an actor surrounds himself with a wah–wah-you’re-too-good durbar, the signs are ominous. Didn’t Rajesh Khanna kick himself out of the market by speeding through the same route?

Clearly, Salman is to popular cinema what a projector is to camera. He can romance, flay fists of fury and tickle the audience’s funny bone with his feather-light comedy (evidenced best of all in Andaz Apna Apna and to a degree in No Entry).

And to think there was a point when SRK’s turnips—Guddu, English Babu Desi Mem, Army, One Two ka Four, Trimurti—didn’t affect his star equity at all. Today, his baiters are awaiting that one dud to bury him. Fortuitously, the extended cameo in Dear Zindagi demonstrated that he is still pretty much alive and acting.

By the way, you can’t help wondering why SRK never teamed up with his Baazigar duo Abbas-Mustan again after Badshah? Could it be because they don’t fit into the profile of his durbar? Having lamented that, SRK is still too street-smart for any kind of downsizing. Inshallah.

By the way, you can’t help wondering why SRK never teamed up with his Baazigar duo Abbas-Mustan again after Badshah? Could it be because they don’t fit into the profile of his durbar? Having lamented that, SRK is still too street-smart for any kind of downsizing. Inshallah.

The third Khan—at this point of time, the hottest Khan—Salman is the classically good-looking one of the trio. Looks? Yes, that traditional attribute does count significantly with the audience. Besides that, he’s uber casual, tossing off performances effortlessly, without taking himself too seriously—epitomised fulsomely in Dabangg, Kick, Ready, Bodyguard, Bajrangi Bhaijaan and Sultan. He dances loonily (the fiddling with the belt of Dabangg was sexually suggestive), he displays his gym-fashioned body and laughs at himself while bashing up the baddies ten times his size.

The third Khan—at this point of time, the hottest Khan—Salman is the classically good-looking one of the trio. Looks? Yes, that traditional attribute does count significantly with the audience. Besides that, he’s uber casual, tossing off performances effortlessly, without taking himself too seriously—epitomised fulsomely in Dabangg, Kick, Ready, Bodyguard, Bajrangi Bhaijaan and Sultan. He dances loonily (the fiddling with the belt of Dabangg was sexually suggestive), he displays his gym-fashioned body and laughs at himself while bashing up the baddies ten times his size.

Salman Khan could have been an all-rounder, but for his unpredictable behaviour which flows from his real life attitude to his screen performances. Frequently, you detect that his dance moves as well as his dramatic pitch are purely of the moment. His voice dubbing is careless, and his low-octave voice barely rises to that key pitch of intensity. One of a kind, Salman seems to be astonished by his own appeal. That’s his saving grace actually. Without this element, his performances could have lapsed into the pits of hopeless arrogance.

Prem is his second name, assigned to him by Sooraj Barjatya, a director whose direction he appears to respect. No wonder, Maine Pyar Kiya and Hum Aapke Hain..Kaun! are Salman Khan’s most charm-oozing performances yet. With Sanjay Leela Bhansali, he was under control in Khamoshi: The Musical and Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (his guest appearance in the director’s Saawariya was vapid though). To David Dhawan’s brain-bending comedies like Judwaa, Biwi No. 1 and Partner, he has contributed unbridled zaniness, in Prabhu Deva’s Wanted, he was the invulnerable man of action, and in Satish Kaushik’s Tere Naam, a weird hair-styled Majnu gone unhinged.

Prem is his second name, assigned to him by Sooraj Barjatya, a director whose direction he appears to respect. No wonder, Maine Pyar Kiya and Hum Aapke Hain..Kaun! are Salman Khan’s most charm-oozing performances yet. With Sanjay Leela Bhansali, he was under control in Khamoshi: The Musical and Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (his guest appearance in the director’s Saawariya was vapid though). To David Dhawan’s brain-bending comedies like Judwaa, Biwi No. 1 and Partner, he has contributed unbridled zaniness, in Prabhu Deva’s Wanted, he was the invulnerable man of action, and in Satish Kaushik’s Tere Naam, a weird hair-styled Majnu gone unhinged.

Clearly, Salman is to popular cinema what a projector is to camera. He can romance, flay fists of fury and tickle the audience’s funny bone with his feather-light comedy (evidenced best of all in Andaz Apna Apna and to a degree in No Entry). Sorrily, when it comes to transmitting sobriety and seriousness—as in Love, Phir Milenge, Kyun Ki and Mr aur Mrs Khanna—Salman Khan is ill at ease. Moreover, his choice of films has been haphazard. For instance, take Auzar, Hello Brother, God Tussi Great Ho and Veer.

Perhaps it’s best to let Salman Khan remain brattish, cool, moody. Because that’s when he acts naturally. At this juncture, he is in a position to take his career wherever he wants to. He’s acted in over 80 films, he’s been written off several times and assailed by ceaseless controversies. Yet he has survived and is smiling wider than any of the other Khans, Khannas and Kapoors of showbiz.

Even among the Khan trio, the numbers keep crunching.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

India News18 hours ago

India News18 hours ago

Latest world news18 hours ago

Latest world news18 hours ago

Latest world news4 hours ago

Latest world news4 hours ago

Latest world news4 hours ago

Latest world news4 hours ago

India News3 hours ago

India News3 hours ago

Latest world news3 hours ago

Latest world news3 hours ago

India News3 hours ago

India News3 hours ago

Coincidentally, all three of them had to linger on the margins before striking popularity platinum. For starters, Aamir Khan the dreamy Romeo of Qayamat se Qayamat Tak (1988), Salman Khan the besotted romantic of Maine Pyaar Kiya (1989) and Shah Rukh Khan the bike-riding lover boy of Deewana (1992) had flitted around like moths to the showbiz flame.

Coincidentally, all three of them had to linger on the margins before striking popularity platinum. For starters, Aamir Khan the dreamy Romeo of Qayamat se Qayamat Tak (1988), Salman Khan the besotted romantic of Maine Pyaar Kiya (1989) and Shah Rukh Khan the bike-riding lover boy of Deewana (1992) had flitted around like moths to the showbiz flame. Once, it used to rain surprises in Shah Rukh Khan’s backyard. His uncontrollable energy, unconventional body language and stuttering dialogue have given him a distinctive appeal through a mixed bag of over 60 films. If Aamir Khan’s voice, dialogue delivery and diction were seductively low-key, SRK’s were disturbing. And if AK’s sunshine smile was a mannerism that his fans demanded consistently, SRK’s toss of shampoo-silk hair, a raise of those diabolical Jack Nicholson-like eyebrows and a pout of his lips became his identifying characteristics. More than any other actor of his generation, he relished risks, caring a damn about the good-guy image by investing a psychotic edge to Baazigar, Darr and Anjaam, and who knows, in the upcoming Raees.

Once, it used to rain surprises in Shah Rukh Khan’s backyard. His uncontrollable energy, unconventional body language and stuttering dialogue have given him a distinctive appeal through a mixed bag of over 60 films. If Aamir Khan’s voice, dialogue delivery and diction were seductively low-key, SRK’s were disturbing. And if AK’s sunshine smile was a mannerism that his fans demanded consistently, SRK’s toss of shampoo-silk hair, a raise of those diabolical Jack Nicholson-like eyebrows and a pout of his lips became his identifying characteristics. More than any other actor of his generation, he relished risks, caring a damn about the good-guy image by investing a psychotic edge to Baazigar, Darr and Anjaam, and who knows, in the upcoming Raees. Heartbreaking sweet on the one hand and intolerably bitter on the other, SRK could be schizoid, two personae-for-the-price-of-one ticket. Striking menace to begin with, he became the nice fella, the cool-kid-next-door with a concatenation of terrific performances in Kabhi Haan Kabhi Na, Yes Boss, Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, and of course, the pitamah of all romances Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge. The nasty stalker had been tamed, he actually wanted to be loved by everyone from his potential in-laws to his barber Billu.

Heartbreaking sweet on the one hand and intolerably bitter on the other, SRK could be schizoid, two personae-for-the-price-of-one ticket. Striking menace to begin with, he became the nice fella, the cool-kid-next-door with a concatenation of terrific performances in Kabhi Haan Kabhi Na, Yes Boss, Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, and of course, the pitamah of all romances Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge. The nasty stalker had been tamed, he actually wanted to be loved by everyone from his potential in-laws to his barber Billu. By the way, you can’t help wondering why SRK never teamed up with his Baazigar duo Abbas-Mustan again after Badshah? Could it be because they don’t fit into the profile of his durbar? Having lamented that, SRK is still too street-smart for any kind of downsizing. Inshallah.

By the way, you can’t help wondering why SRK never teamed up with his Baazigar duo Abbas-Mustan again after Badshah? Could it be because they don’t fit into the profile of his durbar? Having lamented that, SRK is still too street-smart for any kind of downsizing. Inshallah. The third Khan—at this point of time, the hottest Khan—Salman is the classically good-looking one of the trio. Looks? Yes, that traditional attribute does count significantly with the audience. Besides that, he’s uber casual, tossing off performances effortlessly, without taking himself too seriously—epitomised fulsomely in Dabangg, Kick, Ready, Bodyguard, Bajrangi Bhaijaan and Sultan. He dances loonily (the fiddling with the belt of Dabangg was sexually suggestive), he displays his gym-fashioned body and laughs at himself while bashing up the baddies ten times his size.

The third Khan—at this point of time, the hottest Khan—Salman is the classically good-looking one of the trio. Looks? Yes, that traditional attribute does count significantly with the audience. Besides that, he’s uber casual, tossing off performances effortlessly, without taking himself too seriously—epitomised fulsomely in Dabangg, Kick, Ready, Bodyguard, Bajrangi Bhaijaan and Sultan. He dances loonily (the fiddling with the belt of Dabangg was sexually suggestive), he displays his gym-fashioned body and laughs at himself while bashing up the baddies ten times his size. Prem is his second name, assigned to him by Sooraj Barjatya, a director whose direction he appears to respect. No wonder, Maine Pyar Kiya and Hum Aapke Hain..Kaun! are Salman Khan’s most charm-oozing performances yet. With Sanjay Leela Bhansali, he was under control in Khamoshi: The Musical and Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (his guest appearance in the director’s Saawariya was vapid though). To David Dhawan’s brain-bending comedies like Judwaa, Biwi No. 1 and Partner, he has contributed unbridled zaniness, in Prabhu Deva’s Wanted, he was the invulnerable man of action, and in Satish Kaushik’s Tere Naam, a weird hair-styled Majnu gone unhinged.

Prem is his second name, assigned to him by Sooraj Barjatya, a director whose direction he appears to respect. No wonder, Maine Pyar Kiya and Hum Aapke Hain..Kaun! are Salman Khan’s most charm-oozing performances yet. With Sanjay Leela Bhansali, he was under control in Khamoshi: The Musical and Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (his guest appearance in the director’s Saawariya was vapid though). To David Dhawan’s brain-bending comedies like Judwaa, Biwi No. 1 and Partner, he has contributed unbridled zaniness, in Prabhu Deva’s Wanted, he was the invulnerable man of action, and in Satish Kaushik’s Tere Naam, a weird hair-styled Majnu gone unhinged.