India News

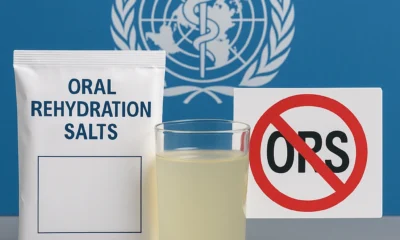

Study links uneven urbanisation with high risk of cholera outbreaks

India News

MK Stalin predicts frequent PM Modi visits to Tamil Nadu before assembly election

MK Stalin has said Prime Minister Narendra Modi will visit Tamil Nadu more often ahead of the Assembly election, calling the tours politically motivated and questioning the Centre’s support to the state.

India News

Shashi Tharoor questions Centre over Kerala name change to Keralam

Shashi Tharoor has criticised the Centre’s decision to approve renaming Kerala as Keralam, questioning its impact and pointing to the lack of major projects for the state.

India News

Tamil Nadu potboiler: Now, Sasikala to launch new party ahead of election

Sasikala has announced the launch of a new political party ahead of the Tamil Nadu Assembly elections, positioning herself against AIADMK chief Edappadi K Palaniswami.

-

India News24 hours ago

India News24 hours agoAs stealth reshapes air combat, India weighs induction of Sukhoi Su-57 jets

-

Cricket news23 hours ago

Cricket news23 hours agoRinku Singh returns home from T20 World Cup camp due to family emergency

-

India News22 hours ago

India News22 hours agoTamil Nadu potboiler: Now, Sasikala to launch new party ahead of election

-

Latest world news10 hours ago

Latest world news10 hours agoTrump says tariffs will replace income tax, criticises Supreme Court setback in key address

-

Latest world news10 hours ago

Latest world news10 hours agoTrump repeats claim of averting India-Pakistan nuclear war during Operation Sindoor

-

Latest world news10 hours ago

Latest world news10 hours agoPM Modi to begin two-day Israel visit, defence and trade in focus

-

India News10 hours ago

India News10 hours agoShashi Tharoor questions Centre over Kerala name change to Keralam

-

India News1 hour ago

India News1 hour agoMK Stalin predicts frequent PM Modi visits to Tamil Nadu before assembly election