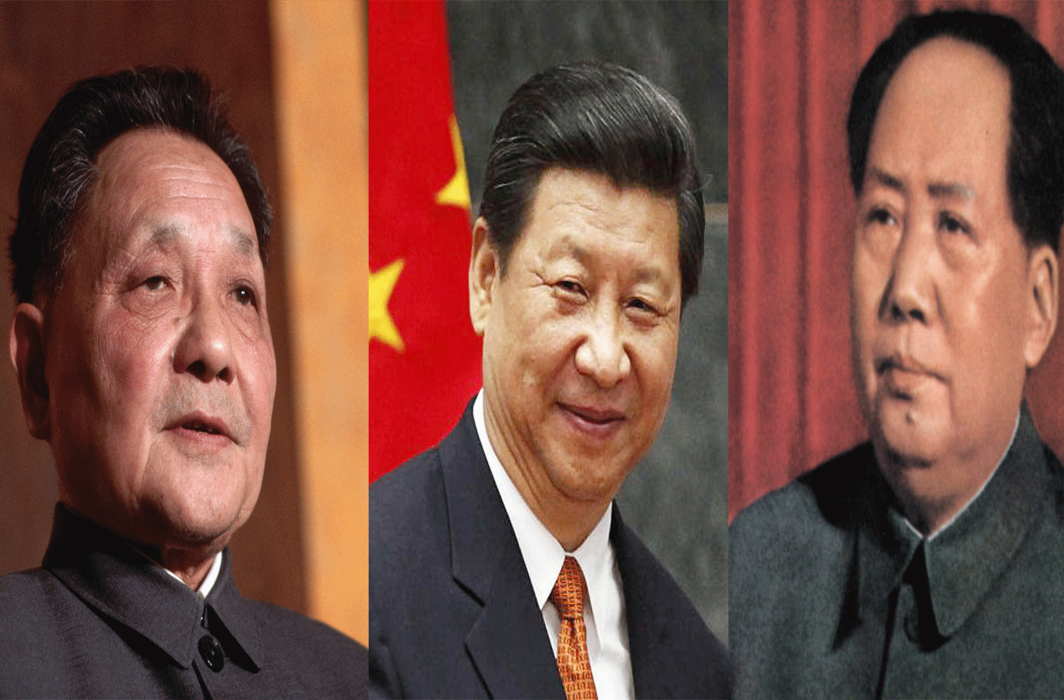

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Mao, Deng and now Xi Jinping. Three of the most powerful leaders in Chinese history. It was Deng Xiaoping who paved the way for Xi to become as dominant a force as he himself was. Dilip Bobb recounts a memorable meeting with Deng in Beijing.

The just-concluded Congress of the Communist Party of China has cemented President Xi Jinping’s place in history as the most powerful leader of the country since Deng Xiaoping. It signposts the end of the Deng Xiaoping era and the beginning of the New Era led by Xi. For veterans like me who were privileged to have an audience with Deng, it brings back memories of the iconic status he enjoyed and the roadmap he laid out which has led to China – and Xi – being where they are at this inflection point in history.

I met the legendary revolutionary on a freezing January morning in 1989 as part of the media delegation accompanying then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi on his history-making visit to China. Being bundled up in layers of wool and thermal, heavy boots and woolen caps covering most of the face, left very little scope for individuality. Luckily, the meeting between Deng and Rajiv followed by a brief reception-line encounter with us lowly scribes was held in the Great Hall of the People, the massive building at one end of Tiananmen Square in Beijing, which had central heating. Chinese officials had briefed us on protocol, distance to be maintained (no handshakes, just a bow or a namaste) and other restrictions to do with his advanced age –he was 84. The briefing and the reverence in their voices when mentioning the ‘Paramount Leader’ made it seem like we were being given an audience with God. In communist, hence atheist, China, Deng was as close to God as anyone could get. His advanced age meant he still had the authority but had become more of a father figure with little official responsibility in the day-to-day affairs of the country.

Still, the veneration and respect with which he was regarded in China had added considerable hype and expectation to the first handshake between an Indian prime minister and the unquestioned leader of China on a bilateral visit. Nehru and Mao had a finger-wagging meeting, but at the Bandung conference in 1954. Since 1961, relations between India and China had been even more frigid than that January morning in Beijing. The Rajiv-Deng meeting represented the potential for a historic breakthrough, or, at the very least, a breach in the Great Wall. There was a discernible sense of history in the making when the two delegations gathered at opposite ends of the ornate and cavernous Great Hall. Rajiv and his official delegation had entered and waited for the Paramount Leader. We, the media clutch, were herded into a corner but with a clear view of the proceedings. Then Deng emerged, disappointingly frail and wizened, but the air of authority around him was unmistakable. The two leaders walked slowly towards each other, Rajiv on his own, while Deng had two aides on either side.

If Rajiv deserves credit for taking the gamble of flying blind to Beijing, it was the all-powerful Deng who orchestrated the turning point during his emotion-charged meeting with Rajiv, a man half his age. The tension in the air was almost touchable as the two leaders converged. Deng, the famous pudding face animated by a twinkle in the eyes, shuffled forward, then stopped, realising Rajiv was still some distance away. The make-or-break enormity of the occasion was reflected in Rajiv’s body language as he moved hesitantly forward, exuding a certain nervousness. Throughout the three-minute-long handshake, he remained unsure and overawed, answering in monosyllables as Deng rambled into reminiscence. In China, however, symbols and semantics are infinitely more important than official declarations. Deng’s opening remarks welcoming his “young friend” and suggesting they “forget the past” was an overt indication that he was literally holding out a hand of friendship. And the next few minutes of their meeting was broadcast through loudspeakers, not so much for the benefit of the world media as for China’s one billion people.

The fact that he spent 90 minutes with Rajiv discussing the changing international scenario and his vision of the balance of power was another signal. A semi-recluse, Deng rarely spends over 30 minutes with visiting leaders. Thus, without actually saying so, Deng was giving his blessings to a burial of the past and the start of another Long March towards normalisation of Sino-Indian relations. After that meet, my brief encounter with Deng was an anti-climax. We shuffled forward in a line, each person pausing for a few seconds to greet the man we had only read about in history books. He would look you in the eye, nod slightly as you were introduced, and then you made way for the next in line. His hands were frail and trembled slightly so the no-handshake rule was logical. Yet, walking away, one could not shrug off the feeling of having just been part of history, even if it was a bit part. Looking back, it is clearer to see the roadmap that Deng left for his successor (Xi was then a regional party chief in Fujian). Deng would die in 1997 but by the time we met him, he had already laid out the essential action plan for China which had just come through the disastrous Cultural Revolution. Called the 24 character strategy, the plan enjoined the Chinese to “observe calmly, secure our position, cope with affairs calmly, hide our capacities, bide our time, be good at maintaining a low profile, never claim leadership.” In other words, China should focus on transforming its economy and keep a low profile in international politics. Towards this end, he advocated the Four Modernisations – of agriculture, industry, science and technology and defence. China adhered to these guidelines with spectacular results and catapulted the opportunistic Xi Jinping to a position where he is now part of the Great Triumvirate of China. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]