Latest Art & Culture

The last kite fighters of India

Published

9 years agoon

By

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The tri-coloured kites that fill the skies on Independence Day in Delhi, opposite the Red Fort from where the Prime Minister addresses the nation, are supplied mostly by Muslim artisans from Bareilly, Moradabad and Lucknow. They are the artists who create the tri-coloured kites, through whose fingers pass the saffron, the white and the green-coloured paper.

~By Shailaja Paramathma

The poet and writer, Munawwar Rana, once wrote:

Ye dekh kar patangen bhi hairan ho gai, ab to chatain bhi hindu musalman ho gai, kya shahar-e-dil me jashn sa rehata raat din, kya bastiyan thi kaisi bayan ba ho gai.

Ayyub Khan, a retired competition kite player, surprisingly, does not agree with these lines. For him, the love of kiting brings all kinds of people together and their religions have never mattered. A life-long kite aficionado, he runs a small shop in Lal Kuan, the biggest kite market of Old Delhi’s Chawri bazaar. The business is so brisk that the shop keepers do not have a minute to waste on you if you are not buying. In this scenario, a fellow-shopkeeper describes Ayyub Khan as a “shokeen” who will take time out to talk about kites with us.

The festival

The 64-year-old Khan points to the sky outside. In mid-afternoon, above a thick network of electric wires and phone cables, there are a dozen kites hovering over the narrow lane in this part of Old Delhi, also known as Delhi-6, a Muslim majority neighbourhood. However, kites on this day are nothing compared to what happens on Independence Day. According to Khan, “the celebrations on 15th August are indescribable, they must be experienced.” Khan says: “15th August here is one big party. Kite-flying is not competitive on the day, what is important is to have fun and celebrate our independence. People try to launch forth their kites high up into the skies. The day begins early; entire households move onto the terrace—if on one roof top, there are kebabs being cooked on an open fire, at another, deep fried aloo patties would be getting prepped to feed the sportsmen. Music systems blare and the mood is upbeat. It’s a community celebration, like any other festival. Evening sees fireworks and some also release tri-coloured balloons into the sky.”

Once Independence Day is past, competitive kiting is back, the junior players go back to holding the spool that feeds the kites of a competition kite flyer. Nazrul, better known in the kiting circuit as Bittoo bhai is a competition kiter from the Saathi Kite Club. He says: “We do not fly kites on 15th August; we are serious players who have played at state level competitions. Rooftop fliers are novices. Tell me, if you have played the Ranji trophy will you then play street cricket?” he asks. Laughingly he adds: “If on Independence Day, a kid manages to cut my kite, he will go about distributing sweets to the entire locality. He will talk about it all year. I can’t take that risk!”

Competition kite-fighters

Competition kite flying is not something many people would know even exists but it is played as seriously as any of the other popular sports. The Delhi Kite Flying Association has some 237 registered clubs and around 200 more are seeking registration. Each club has between nine to 12 members. In competition, only three players from each team get the opportunity to kite. Large clubs will mean that some members will never get to compete, hence the more the number of clubs, the more the number of competitions and more people get to play. It is a gentleman’s game and rules are binding and followed to the T! Even though a formal rule book does not exist, rules laid-down by senior players over the years are respected. And just like in law, when there is no clear rule, precedents are cited and followed. In case of a dispute the elders are consulted and their word is honoured. Before the competition a thorough check of the dimensions of the kites and the manjha takes place by the association. Any attempt at using the Chinese manjha (which is very much made in India) will result in a ban and a loss of face in the kite flying community. While the winner is treated like a local hero, if anyone cheats he will not only be out of the association but also disbarred from competing for life. Bittoo bhai says: “Experienced players can tell by the angle of attack and the result thereof if Chinese manjha is being used because it behaves differently.”

Kite tournaments are held at state and national level. In Delhi, it is conducted by the All India Kite Association. Matches are played on a knock-out basis. To play, each team registers four players, three compete and the fourth is the reserve player. A team receives nine kites in total, three for each player. The duel begins; one player from each of the two teams in the match enters an 8 feet x 18 feet area on the field which is cordoned by a rope, called the crease. The two boxes are a few feet apart from each other. Outside the box, an aid holds on to the spool of thread attached to the players kite. A whistle blows and the two kites are launched into the air. An opposition player is stationed right next to each box and has the job of arresting the foot of the player, if it touches or crosses the crease. This foul costs one point. Up above, the two kites hover nearer and nearer to each other. Time suspends as the two cotton threads intertwine and rub against each other, as soon as the two lines begin to grapple with each other, the front umpire raises a green flag, signalling to all that a tug is on. When one line is cut, the flag comes down and is pointed at the winner. One game can last between 15 to 20 minutes. There are three referees and in case of a dispute the decision of the third referee is final and binding. The winner gets one point and waits in his box as the loser is replaced by the second contender. The match begins anew. To win, the team needs nine points. The festival spans over a fortnight, match after match, weak teams are weeded out till there are just two top teams remaining.

Khan says: “Ban on Chinese manjha did bring business down but since I saw a picture on my son’s phone, of a little girl, her neck cut off from her body due to the manjha, I swore I will not sell Chinese manjha even if I suffer losses. Clients come and insist that they want Chinese manjha, they even try to coax me. I don’t like such insistence; I try and tell them about the accidents. Some listen, some don’t.”

Keeping it alive

Mohammad Atif, 40, who is in the business of supplying drinking water, has been competing for around 26 years. “I started competing at the age of 14. As players, we train all week, either in the maidan or from our rooftops. We call each other and show-up on our respective terraces with kites in our hands. That’s how we meet to practice.” Atif has travelled to Lucknow, Bareilly, Mathura, Bikaner, Jaipur, Meerut, Moradabad and Aligarh to compete in various kite flying competitions. “But the money spent on travel is out of our pockets. The stay is free and if we win the prize money is ours too,” but he adds dispassionately: “We have to hide our junoon from our families. My wife does not complain, however, my relatives often tell me to give up kiting. And my 14 year old boy is embarrassed that I still fly kites. His friends pull his leg over it. For them, it is something you do only on 15th August.”

Arish Saleem, captain of Hamdard kite club, which was established in 1974, is a goldsmith by profession. He says: “We are addicted; we meet every night after finishing work and dinner, in Balimaran, to discuss life, the games and new flying strategies.”

Bittoo bhai laments the lack of recognition the sport gets from the government or the people, “Many efforts were made to bring more focus and interest into this sport but there were also many who did not want it to happen. And then at times when competitions were organised, for two days in a row not a shred of wind blew, people kept waiting. Or such a strong gust came that it tore the kites apart.” He does not want his kids to kite unless this sport is recognised by the government: “I want them to study and have respectable careers. My father does not approve of my hobby as he thinks it is a waste of time and money.” “Patangbazi is viewed just like kabootarbazi,” he adds regretfully.

Even though most kites are inexpensive, a good quality one can cost up to ₹40. The manjhas are costly, a quality one sells for around ₹2,000 for a spool about 10,000 meters long. Saleem says: “As soon as I launch my kite into the air, it has already cost me material worth ₹200. If I lose a few while practising, by night the activity has cost me over 500 bucks. All for getting a high from a good match.”

Bittoo bhai says: “A player finds recognition only when he reaches state finals, or wins a trophy or a certificate. The prize money at the all India level is ₹51,000. A win in Delhi can get you a cash reward of ₹21,000 to ₹25,000. When my Ustad won the all India trophy, he threw a party for 400 people, and ended up spending ₹80,000. In 2011, I was first runner-up at the all India level, I won ₹31,000 and spent ₹39,000 on the party I threw. It is a serious addiction.

The kiting lores

In this meandering lane, a sudden monsoon shower does not halt life. If you are not from the area, the locals see that without even looking at you and cede you extra space, squeezing themselves deftly in-between a stationary rickshaw and an oncoming wheel-barrow.

A duo of pre-teen boys, wearing white lace skull caps, walk with their arms over each other’s shoulders, holding a few tri-coloured kites among others in their hands. Khan says: “It’s not just the Hindus who buy the tri-coloured kites. Everyone buys them, irrespective of their religion. I do not think there is any difference between people, that sentiment is propagated only by a few.”

It is said that kiting became a craze when a paralyzed man was brought to the legendary Hakim Luqman, who made a special kite for him and asked him to fly it. The patient followed the instructions and soon was walking again. Khan says: “It’s a sport that provides overall exercise, from your hands to your arms, from the chest to the legs. It also sharpens your eye sight, and your brain.” Hakim Luqman is best known for his last experiment—it is said that he cut up his body to cause certain death but also made a magical powder to revive him upon reaching his last breath. He handed over this powder to his aid and began the procedure of cutting himself open, just when the aid was supposed to give him the powder and revive him, a gust of wind came and the powder blew away. In the blink of an eye, both the powder and the Hakim were gone, just like a kite!

The heros

Kites made by Mobin Khan are considered collector’s items. Zhahin Niyazi is a kite maker from Bareilly, whose kites carry his stamp and a small picture. His kites are known for their quality and their designs; they sell for around ₹80 a piece. The manjha spools also carry the pictures of the makers. Ustad Razi from Moradabad and Shahabuddin from Lucknow sell the costliest. A master kite maker and artist-kiter who was affectionately called Babu Khan by everyone was known to launch one kite in the sky and then add more and more kites to the same line, creating a visual delight in the sky. A guest of honour at every kite festival in India till his death, Babu Khan could make from the smallest to the biggest kites, all of which would fly superbly.

The kiters say that in this game age or gender is no bar. There are many women kite flyers who have participated in various competitions in Lucknow and Jaipur and Bikaner have full-on women teams. However, old Delhi is yet to produce its own woman kiter.

In every country, nationalist jingoism is at its zenith every independence day, and India is no different. 15th August is marked by an amazing increase in kite flying. The tri-coloured kite is the most sought after and the suppliers who feed the jingoism of the day are Muslim artisans from Bareilly, Moradabad and Lucknow. They are the artists who create these kites, through whose fingers pass the saffron, the white and the green-coloured paper.

Moin Khan, the son of Ayyub Khan, is a thorough businessman who has no interest in kiting. In a very practical tone he says: “The tiranga belongs to all us Indians, no matter our religion. If one particular group uses the flag as their own property, it is disrespect to our flag. Muslims have always proved their loyalty to India and they don’t have anything more to prove. So, if people cannot see that I am as patriotic as them, I cannot help it. That said, I feel disappointed with the state of affairs these days and hope the government will do something to stem this rising feeling of communalism. I do not feel hatred for those who are different from me but I do question who brainwashes them.”

After the success of the movie Maine pyar kiya in the 1990s, the markets were flooded by kites with Salman Khan’s pictures. From time to time cricketers are also featured on them. Children go for the glitzy ones with cartoon characters like Doremon, Motu-Patlu, Shiva, Chota Bheem and Barbie.

For the last three years, kites have started featuring Narendra Modi too. For a kite market which is situated only a stone’s throw from Ghalib’s haveli, people toss-about shers like everyday maxims. One that we hear as we are leaving is—Patang si hai zindagi, kahan tak jayegi. Raat ho ya umr, ek na ek din kat he jayegi.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

You may like

-

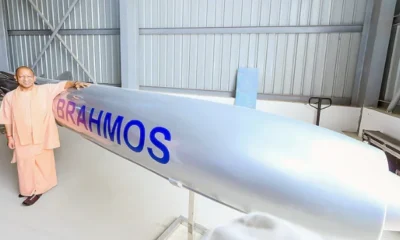

Rajnath Singh, Yogi Adityanath flag off first batch of BrahMos missiles from Lucknow facility

-

Bareilly tense after I love Muhammad row, police lathicharge protesters

-

Zikra, woman don from Delhi, sent to 2-day police custody in Seelampur murder case

-

BJP appoints district presidents for UP’s 68 district, check names here, CM Yogi Adityanath extends congratulations

-

Two arrested after British woman gang-raped in Delhi hotel

-

Delhi Minister Manjinder Singh Sirsa says no fuel for vehicles older than 15 years after March 31

Book reviews

Almost 10, Raisina Chronicles reveals the leaps and challenges of Raisina Dialogue, read review

Published

11 months agoon

March 20, 2025

By Subodh Gargya

Raisina Chronicles is a book based on the Raisina Dialogue, a multilateral conference on global politics and economy, which has been held every year in New Delhi since 2016.

The programme is organized by the Ministry of External Affairs and the Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar and ORF President Samir Saran have edited Raisina Chronicles, a book marking the completion of 10 years of the Raisina Dialogue. It explains how the Raisina Dialogue is a medium for countries to discuss challenges facing them led by India.

The Raisina Dialogue’s message highlights India’s growing influence in the world. The book is a bird’s-eye view of geo-political events in the last decade and the views of world leaders on them. The book includes speeches given by world leaders during the Raisina Dialogue.

The first section describes the changes in the global system. This includes the speeches of PM Modi and UN Secretary General António Guterres. The second section explains how countries around the world have come together on some things. The third section dwells on new opportunities for Europe in the Indo-Pacific region. The fourth section discusses security around the world while the fifth explains how Covid-19 has given countries an opportunity to think anew. The sixth section outlines a new perspective on development. In the seventh and final section, it focuses on India’s role and the contribution of the Raisina Dialogue.

The book shares PM Narendra Modi’s view that in today’s time, listening is more important than speaking. Every idea should be heard, thus dialogue is the food of life.

Apart from communication between countries, the editors of the book clarify that its purpose is also to work on differences as the platform respects diversity in ideas. Leaders, business, media, journalists and people from civil society participate in the Raisina Dialogue.

Book reviews

Walking On The Razor’s Edge: The path of the seeker

Published

2 years agoon

July 19, 2024

The Power of Karma Yoga by Gopi Chandra Das (Jaico Books) is an attempt to unravel the mystique of the Bhagavad Gita in the contemporary context. Is Lord Krishna’s counsel to Arjuna still relevant in today’s time and social space ? How can the timeless teachings of Lord Krishna be adopted by people struggling to cope with the stresses and challenges of modern life? Is there a key teaching which can be easily adopted by stress-torn people? These and many more questions are answered by the author in his easy-to-read style.

The basic premise is that the stress is a function of identity; identity with ego or with role-playing. We all play roles in life: in the family, the office and in the social sphere. These roles demand close identification and exact their cost by way of fear, frustration and failures.

The way out is to ease one’s sense of identity with one’s temporal roles. At the metaphysical level, it means keeping oneself in a detached state from one’s ego. This requires sustained spiritual discipline, but automatically yields to mental distancing with mundane roles as well. No wonder the Katha Upanishad compares the spiritual path to a razor’s edge.

Lord Krishna sought to instil this detached perspective in Arjuna by underlining the perishable nature of the body and the transitory nature of the world. However, the key is to strike a balance between total detachment and total attachment. The golden mean is attained by letting go with discrimination. If we detach too much, it will become difficult to perform our duties; if we cling too much, the material will become a millstone. The idea is to be in the world and yet not be of it. As the Persian saint Abu Said said, “To buy and sell and yet never forget God.”

Detachment, however, doesn’t mean irresponsibility. On the contrary, it means working with utter responsibility; with a sense that the job at hand is a moment to glorify the divine. It is not only work for work’s sake; work is taken up as a tool for self-realization. This is more deeply grasped if we acknowledge that the Gita is not only a handbook of divine knowledge or spiritualised action but essentially a guidepost for the man treading the path of enlightenment.

Sri Aurobindo says: “The Gita is not a weapon for dialectical warfare; it is a gate opening on the whole world of spiritual truth and experience, and the view it gives us embraces all the provinces of that supreme region. It maps out, but it does not cut up or build walls or hedges to confine our vision.”

Or as Paramahansa Yoganananda puts it: Gita sheds light on any point of life in which the devotee finds himself in.

Delving yet further, Gopinath explains in the book that letting go is made easy by the practice of apagriha, or being unattached to desires with conscious control on attachment-driven strivings. In the process, one’s motive gets transformed from want-driven to purpose-driven. The aim, at the highest level, being self-realization: the acme of spiritual strivings. For all material strivings ought to be in essence spititual strivings.

When we shift from want-driven to purpose-driven action, the need for personal validation ceases. In our quest for a spiritual-centric action mode, yagna plays an important role. The concept of yagna is transposed from a religious fire-rite to diurnal mundane acts in which personal motives are quenched. As the borderline between the spiritual and the material gets increasingly dissolved, the quest for enlightenment becomes the summum bonum of life.

The direction and blessings of a sadguru is also needed in this eternal quest for soul freedom. In the ultimate sense, the material life and its duties become a stepping stone for a higher life which man embraces to achieve the state of kaivalya. The book lucidly interweaves real-life stories with philosophical concepts, which make for interesting reading.

Entertainment

Justin Bieber shares unseen pictures from Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant pre-wedding sangeet

Justin Bieber’s energetic performance on Friday was the highlight of the sangeet ceremony, which took place at the Nita Ambani Convention Centre in Bandra, Mumbai.

Published

2 years agoon

July 7, 2024

Global popstar Justin Bieber brought the energy at Anant Ambani and Radhika Ambani’s pre-wedding sangeet on July 5 in Mumbai. The soon to be married couple (wedding in July 12th) was spotted enjoying themselves as Bieber belted out his hits. While glimpses from the night went viral earlier, Bieber has now shared unseen photos and videos from his memorable trip to India.

The heartwarming pictures show Justin Bieber bonding with Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant and their family. In one picture Justin stands with Anant and Radhika, all three dressed festively for the sangeet ceremony. Another photo captures a casual moment where Justin Bieber is seen chatting with Akash Ambani on a couch while Anant and Radhika are posing with him.

The group also posed for a larger picture that included Shloka Mehta and Anand Piramal. The final photos show Justin Bieber and Anant Ambani engaged in a friendly conversation, solidifying the warm atmosphere of the visit. Justin’s trip to India started on Friday morning with his arrival in Mumbai.

https://www.instagram.com/p/C9FvfWxIpQX

That night Bieber transformed the Jio Convention Centre into a party zone with his hit songs and celebrities like Salman Khan and Alia Bhatt grooved along with him. Videos circulating on social media show Justin Bieber dancing with Orry and receiving a hug from Alaviaa Jaffrey( daughter of Javed Jaffrey). According to reports Justin Bieber has been paid $10million for this special performance.

https://www.instagram.com/p/C9Fu5I5oxBm

Bieber’s energetic performance on Friday was the highlight of the sangeet ceremony, which took place at the Nita Ambani Convention Centre in Bandra, Mumbai. The singer made the guests groove on his songs Baby, Love Yourself, Peaches, Where Are You Now and Sorry. Bieber’s fresh off his triumphant return to the stage once again set the internet ablaze with his electrifying performance at Anant and Radhika’s sangeet ceremony.

Pakistan declares open war after Kabul strikes, claims 133 Afghan fighters killed

Rinku Singh’s father dies of cancer during T20 World Cup campaign

Rohit Pawar alleges big personality link in Ajit Pawar plane crash case

Rohit Pawar alleges big personality link in Ajit Pawar plane crash case

Rinku Singh’s father dies of cancer during T20 World Cup campaign

Pakistan declares open war after Kabul strikes, claims 133 Afghan fighters killed

Over 5,000 tribals join BJP in Assam’s Goalpara ahead of elections