West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has intensified her attack on Prime Minister Narendra Modi amid a growing dispute over President Droupadi Murmu’s recent visit to the state.

Speaking at a public rally, Banerjee referred to a photograph from March 2024 that shows the President standing while the Prime Minister is seated during a meeting with veteran leader Lal Krishna Advani. The Trinamool Congress leader questioned the government’s claims about respecting the office of the President.

According to a video shared by the Trinamool Congress, two party leaders displayed the photograph while Banerjee addressed the gathering. She argued that while leaders often speak about honouring the President’s office, such visual moments raise questions about whether that respect is truly reflected in conduct.

The photograph referenced by Banerjee was taken on March 31, 2024, when President Murmu and Prime Minister Modi visited Advani to present him with the Bharat Ratna.

Banerjee said the image showed the President standing while the Prime Minister remained seated. She asked whether the government truly respected the country’s first tribal woman President, adding that the picture demonstrated “who respects and who does not”.

President’s visit to Bengal triggers controversy

The political exchange began after President Murmu visited West Bengal on Saturday to attend the ninth International Santal Conference in Darjeeling.

While addressing the event, the President publicly noted that neither the chief minister nor other state ministers were present to receive her. She said that usually the chief minister welcomes the President during such visits but that did not happen in this case.

Murmu added that Banerjee is like a “younger sister” to her and said she did not know whether the chief minister was upset.

The President also raised concerns about the change in the event venue and suggested that the new location made it difficult for people to attend. She said she did not know why the state administration had not permitted the programme at the earlier venue.

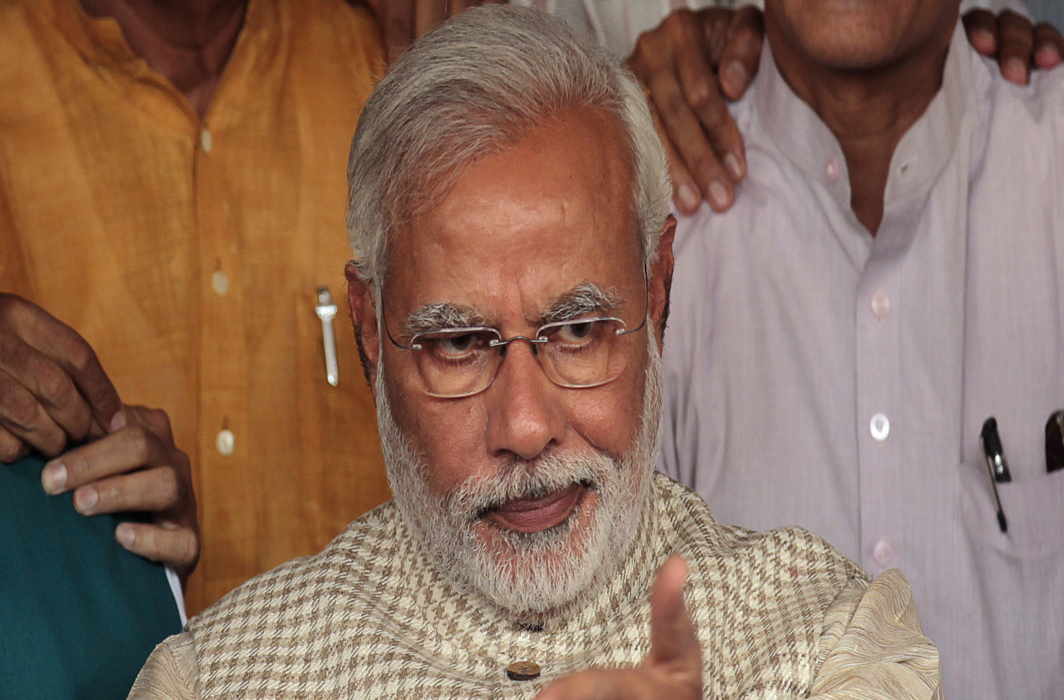

Prime minister criticises Bengal government

Reacting to the developments, Prime Minister Modi described the situation as “shameful and unprecedented”. In a post on social media, he said the incident had saddened people who believe in democracy and in empowering tribal communities.

He added that the pain expressed by President Murmu had caused widespread concern and accused the West Bengal government of disrespecting the office of the President. The Prime Minister also said the dignity of the President’s position should remain above political disputes.

Speaking at a public event later, Modi said the developments were particularly unfortunate as they occurred on International Women’s Day. He alleged that the Trinamool Congress government had boycotted both the tribal event and the President.

Mamata Banerjee denies protocol violation

Banerjee rejected the allegations, saying no protocol lapse occurred during the visit.

According to the chief minister, the event had been organised by a private body, the International Santal Council, which invited the President to attend the conference in Siliguri. She said the district administration had warned the President’s Secretariat that the organisers lacked adequate arrangements to host such a programme.

Banerjee also stated that the advance team from the President’s Secretariat visited the site earlier in March and was informed about the shortcomings but the event continued as scheduled.

She added that officials including the mayor of Siliguri Municipal Corporation, the Darjeeling district magistrate and the Siliguri police commissioner received and saw off the President according to the approved protocol lineup.

The chief minister said she was not part of the official lineup or the event’s dais plan and accused the BJP of using the country’s highest constitutional office for political purposes.

Centre seeks report from state

The issue escalated further after Union Home Secretary Govind Mohan wrote to West Bengal Chief Secretary Nandini Chakravorty seeking a report on alleged lapses during the President’s visit.

According to sources, the letter asked why senior state officials such as the chief minister, the chief secretary and the director general of police were not present to receive the President. It also raised concerns about reports of poor arrangements at the venue, including the absence of water in a washroom designated for the President and garbage along the route.

Officials from the Darjeeling district administration and Siliguri police were also mentioned in the communication, with the Centre seeking details of any action taken.

The controversy has now turned into a sharp political confrontation between the Centre and the West Bengal government.